|

|

Troubleshooting Bringsel TrainingThe bringsel is not a toy and only serves as a tool with which the dog shows its find. Don’t let the dog play with the bringsel. The dog can work out its drives on the sock toy, which the dog gets when it comes back to the helper. The dog doesn’t have to take the toy anywhere and can decide all by itself how it wants to play. The dog can do whatever it wants with its sock toy, except destroy it. The handler should stimulate and support the dog in this play as long as the dog needs it. Some problem phases can occur while working with the bringsel: • The dog picks up the bringsel at any human odor, without finding the helper or victim. Solution: Immediately correct with “No.” Give the bringsel back to the helper for a time. • The dog picks up the bringsel near blankets, plastic, or other items on the ground. Solution: Build these situations into training and, if necessary, correct immediately with “No.” • The dog picks up the bringsel at a spot where a helper was lying shortly before. Solution: Bring this situation into training and correct where necessary. • The dog picks up the bringsel at a standing or walking person. Solution: If you don’t want the dog to alert to standing or walking people, correct the dog immediately.

If there are more problems with the bringsel training, start the training again from step 2. Proceed through all the steps as they can be completed without problems. Do not teach ranging in the same exercise as the bringsel alert. When a dog is learning ranging, it is often under pressure and will try to please its handler (incorrectly) by picking up the bringsel!

Figure 8.10 The dog comes back to its handler carrying the bringsel.

Training the Recall Alert With the recall alert, the dog will travel on its own between the handler and the helper to lead the handler to the helper. Ordinarily there is no need to teach this. When the handler also reaches the helper, then the dog receives the sock toy. Important in the recall is that the dog shows a very clear behavior, so that the handler knows the dog has found a victim. Clear behavior patterns are barking to the dog handler, jumping up at the dog handler, or sitting in front of the dog handler. Taking a slip of the jacket or picking an article from the belt of the dog handler is also clear. Going back to the victim can be done on or off leash. The beginning of recall alert training is the same as bringsel training, but here you can also use biscuits if the dog does not like toys. The training victim has two toys, one of which is the sock toy. The first toy is picked up from the helper and the dog brings it to you. If you like a special behavior, such as sitting in front, tell the dog to sit, take the toy from the dog, and give it a biscuit. Then the victim calls the dog. The dog runs back to the victim and gets the sock toy to play with. As soon as the dog understands this training at a distance of about ten yards (10 m), you can change the circumstances, helpers, or distances. If the dog does not like toys, the victim can give the dog some biscuits when it first reaches him or her. Then you call the dog, which then runs back, sits in front of you, and again gets some biscuits. After that, encourage the dog to run a second time to the victim by running with it toward the victim. Once there, the dog again gets some biscuits and after that the sock toy if he likes it. Now the dog is allowed to play however it wants with the sock toy, and in the end the normal ritual of prey sharing will happen. Dog handlers have to observe the behavior possibilities their dog shows. Many Border Collies and Australian Shepherds like to bark close to the dog handler if they are excited about finding a person. They don’t like to stay with the victim, but instead like to go to their handler to show they have a find. This behavior can be stimulated and strengthened by rewarding the dog with biscuits or a toy. As soon as the dog understands that it has to turn and run to the dog handler after finding a victim, show the handler its special behavior pattern, and then run back with the dog handler to the victim, the next steps in training can be made. You can follow steps 9 to 12 in Training the Bringsel Alert. Training Ranging Along with alerts, we teach search and rescue dogs to carefully search an area under the direction of the handler. The goal of this training is to develop an independent search pattern to use during operations. Training for ranging can begin when the dog’s alerts for a sitting or lying victim are consistent. This means the dog is barking continuously and staying with the helper, is bringing the bringsel correctly to the handler and correctly going back to the helper, or in the case of the recall alert, shows an easily recognizable behavior pattern near the handler after finding a victim and commutes well between handler and helper. The International Testing Standards for Rescue Dog Tests (IPO-R) explains ranging as follows: “On the instructions of the handler the dog must comb both sides of the search area.”4 This means that the dog has to search the area alternately left and right in deep lateral run-outs on command of the handler.

Figure 8.11 The dog has to develop good speed in ranging the area.

Figure 8.12 The dog has to search an area systematically even during high or low temperatures.

Figure 8.13 In this ranging pattern, used by the Schutzhund program, the dog always moves forward. The standing helpers entice the dog to teach the ranging pattern, but the dog should not alert at them.

Step 1 The best way to teach ranging is to start on a path in front of a reasonably open wooded area. Two helpers, visible to the dog, should stand about twenty-seven yards (25 m) away, one to the left of the dog and the other to the right. These helpers define the edges of the search area. Now have one of the helpers sit or lie down in sight of the dog and then send the dog to the sitting or lying helper with the command “Left” or “Right.” The rest of the exercise will be worked out as usual. With barking, the dog must repeatedly or continuously bark until the handler arrives, and then it gets its sock toy from the helper. With the bringsel alert, both helpers have to take a bringsel and a sock toy with them. With the recall alert, the dog gets its sock toy from the helper only once the handler reaches the helper with the dog.

The play after the first alert will now be kept a bit shorter. After the prey sharing, send the dog with the command “Right” or “Left” to the other side, where the second helper is sitting or lying.

Figure 8.14 This grid pattern for ranging allows the dog to search backwards around bushes, trees, and other features.

Step 2 Next, both helpers, one on either side of you, walk a few steps forward into the woods, and you should also go a few steps in (the woods should not be too overgrown). The places at the sides that the helpers walk into should ideally be a little more overgrown, and this time the helpers should stand. Send the dog again in one direction: to the right, for example. If necessary, the dog can be called by the helper to make it enthusiastic about walking in that direction. Remember that the dog may not alert at the standing helper. Barking or another attempt at an alert must be immediately stopped with a firm “No” from the helper. It is not important if the dog occasionally passes the standing helper. Never restrict the distance the dog goes by itself (unless the dog is doing something else, such as chasing rabbits). Step 3 As soon as the dog is at (or passing) the standing helper at the right, call it back with “Here,” “Back,” or “Turn.” Before the dog reaches you and stops, send it immediately to the left. The dog should run past you in the new direction in a smooth tempo. The helper standing on the left can entice the dog by calling it. You might also run a few steps to the left along with the dog to motivate it. If the dog does not go far enough to the left, then there’s usually no sense in forcing it by command to walk farther. It is better to call the dog back and send it running again directly to the right. After it arrives at the standing helper there, call the dog back and send it more enthusiastically to the left. If necessary, the helper on the left can lie down in sight of the dog, giving the animal a clue as to what is expected. Step 4 After at most three turns, one of the helpers has to lie down on the ground again, so that the dog is successful. Handlers often let their dogs search too long without locating a “victim” during training. Ranging has to be built up slowly and carefully. Take care that the dog is enthusiastic and in condition to run back and forth. If the dog starts to lose interest or gets tired, then a training helper should lie down as a victim. If this happens, finish the exercise and repeat it again after an hour. Take care that the dog doesn’t walk too far ahead of the handler. Dogs have a strong inclination to walk ahead into an area. This inclination will sometimes be strengthened by handlers (and also the helpers on the edges) walking forward too slowly. The dog then is forced to search an area it has already covered, so it goes forward on its own. The helpers on the edges have to take care that they are not ahead of the handler, because that also encourages the dog to walk ahead. Step 5 The ultimate goal is to teach the dog to travel in loops and range in a figure-eight pattern rather than running out and back along the same path. The helpers on the outer edges can encourage the dog to make bigger curves by walking outward farther and enticing it. If this works well, then they can hide standing behind bushes or bigger trees, so that the dog can’t see from a distance whether the helper is standing or lying down. Helpers also can try to entice the dog from another place at the sideline (before or behind) and then let it go back. Step 6 If step 5 is successful, then we can let the dog search once again with the bringsel fixed on its collar. If problems occur, immediately go back to working the dog without the bringsel on its collar for a time. Have the dog receive the bringsel from the sitting or lying helper. Step 7 Continue to work the dog in the well-known wooded area, and begin again with the left to right exercise from the path. Now both helpers in the woods should be out of sight and standing. They are allowed to entice the dog by calling it. Every now and then one of the helpers should sit or lie down, so that the dog can alert correctly. Depending on how well the dog learns this stage, it can work with a bringsel on its collar next. Step 8 The next step is to have a helper on one side only. The dog must then first alert to a helper and, after a short sock toy playing and prey sharing session, then make an empty circuit in the other direction. On the third curve (as you and the helper continue walking farther into the search area) the helper lies down again. If this step is successful, then you can extend the exercise to include more empty curves (with the helper on one side standing up). Step 9 Next, one helper can walk at the side and on the other side a helper can be hidden farther into the search area (and can be found only after several empty loops). As much as possible, have the dog work with a tail wind, so that from the start it can’t smell the victim; otherwise it will immediately run ahead in the area, which will ruin this exercise. As much as possible, teach the dog to range the area correctly in nice, wide curves. You don’t want your dog to learn that going straight forward is successful. But if the dog gets the victim’s odor too soon, then let it go and wait for its alert. Take care that this doesn’t happen too often. Step 10 The last step in training is to range in a grid pattern without helpers on the sides. It is important that the dog first be able to make nice curves in the area and doesn’t directly break out of the pattern to alert for victims. If that happens, then have the helpers first stand in the area where later they are to lie down. The dog is not allowed to alert on these standing helpers. As soon as the dog searches properly and comes near, the helper can sit or lie down.

Build your dog’s skills step by step. Never introduce two new steps at once, whether it be new circumstances (new search area, new helpers), increasing distances, or the next step in training. If something is not going well, then go back to the beginning and repeat steps until the dog can progress. Case Study: Rescue Workers on Four Legs The Austrian journalist Monika Rittberger published the following article in an Austrian dog magazine and the Dutch dog magazine Onze Hond (Our Dog). We reproduce it here with permission.

A passenger car has just crashed in the dark night. The car shows serious damage. Traces of blood are found in and around the car, but there is no trace of the driver, a good reason for the Austrian Police to immediately call out the search and rescue dogs of the Austrian Red Cross. If the driver has not fled the accident scene, it is possible that he walked away and lies wounded in the surrounding area, in shock after the accident. In that case, he has to be found quickly. At this time of the year, it gets quite cold at night, and hypothermia and shock are life threatening. Intensive In a quarter of an hour, seven handlers and their dogs from the Red Cross are on the scene. The first handlers immediately try to find a track in various directions, but they are not successful. Too many people have walked over the area, as has happened on many other occasions. The handlers decide to perform a corridor search over the area with their search and rescue dogs. Thorn shrubs, slivers, stones, and barbed wire are no obstacles for the teams. Two kilometers from the accident scene, one of the dogs is successful. By bringing the bringsel on his collar to his handler, the dog tells him that he has found the wounded driver. The handlers immediately give the confused man first aid, which is, of course, another skill of the Red Cross dog teams. Searching for lost people, missing hikers and climbers in the Alps, and avalanche and other disaster victims are the most important tasks of the Austrian Red Cross’s search and rescue dog handlers. Fortunately, they are usually successful. But success with search and rescue dogs does not happen by itself; it must be trained for. Each year every handler of the Red Cross volunteers about 550 hours (more than ten hours a week) to train his or her search and rescue dog.

Figure 8.15 At examinations and trials, a dog must correctly retrieve the bringsel for its handler to be judged fit for operations.

Work Without Stress “Intensive training, but particularly purposeful training methods, are the key to the success of our dogs and their handlers,” says the chief of the Red Cross Dog Teams in Wiener Neustadt. “We have to train regularly in varying circumstances to keep our dogs at the same high level. In an avalanche or earthquake mission, time is the most serious enemy of rescuing people alive. The better the dogs are trained and the longer they can work, the better the chance for survivors. That means that our dogs always have to be in very good search condition, physically and mentally. Everywhere they say that dogs can search intensively for only fifteen to twenty minutes, but we have several times proven, for instance during big practices with INSARAG, the International Search and Rescue Advisory Group of the United Nations, that our dogs can search on the rubble intensively and consecutively for more than three hours,” he says with justifiable pride. When I ask him the secret of their success, he says, “Ask the two Dutch there.” I look at him a bit incredulously, but he is already pushing me in their direction. In front of me stand Dr. Resi Gerritsen and Ruud Haak, who have been training search and rescue dogs for about thirty years. Many years ago they were, because of their experience, asked by the Austrian Red Cross to train and assess their operational search and rescue dogs. Their methods and results had become known during their cooperation with the Austrian Army at the Armenian earthquake disaster in 1988…. In the beginning the Austrians were a bit skeptical, but that soon disappeared when they saw that these Dutch people were fully experienced in wilderness searches, as well as disaster searches and avalanche searches. And what was perhaps most important, they could teach their Austrian colleagues what they knew very well. Going back to the question about the secret of the success of the Austrian Red Cross dogs, I get this answer from them: “Yes, it’s thanks to our purposeful training method and the fact that our dogs are working without pressure. A dog gets the most tired when he works under pressure. When he has to work because it’s what the handler wants or when he is constantly encouraged and corrected, that’s asking for the dog to get tired. Of course, search work is very intensive for a dog, but when the dog may work for his pleasure, or even better, when he, so to speak, asks to work himself, he can work for hours. Our method is designed to allow the dog to develop his enjoyment in searching, without any pressure. He has to work everything out himself, step by step, each time a bit more difficult, without realizing it. That way, he learns to develop himself further and because he enjoys it, he is able to extend his limits, including his stamina.”

Figure 8.16 Dr. Resi Gerritsen (pictured) and Ruud Haak have regularly won the World Championship for Rescue Dogs and they have been Hungarian and Austrian champions several times.

Best Results They know what they are talking about. For many years this Dutch couple has been giving seminars for training search and rescue dogs, not only in the Netherlands and Austria, but also all over Europe and the United States. In that time, they have had many different breeds and mixed breeds in their seminars. “Every different breed, yes, every different dog requires a different approach to bring him to the best results.” These best results have been reached by Gerritsen and Haak regularly in the past with their own dogs: In tough competitions they won the top spot at the World Championship for Rescue Dogs, and have several times been Hungarian and Austrian champions. Their colleagues in the Austrian Red Cross have also won places on the stage of honor. “But that can’t be the most important thing,” they quickly say to me, when I write that down. “Our dogs have to prove themselves on actual search missions. That is the most important, and only that counts!” The search and rescue dogs of the Austrian Red Cross are among the best in the world. They have proven that during operations in their own and foreign countries, where they saved the lives of countless people or gave families their relatives back. In international competitions for search and rescue dogs, the Red Cross dog handlers have reached the top in the face of serious competition! To show something of the training method, Speedy, their fourteen-month-old Malinois female, goes to work. Passionate and with the characteristics of a wonderfully relaxed young working dog, she shows why they gave her that name. She is working with a so-called bringsel that hangs on her collar, and she is allowed to pick it up when she finds a hidden person. On indication from her handler, she runs from the right to the left through the brushy wooded area. She works out the indications very attentively, and without delay she ranges nicely through the extensive area. Then suddenly she gets a whiff of the hidden person. Very quickly, she runs to that person. There, she immediately takes the bringsel in her mouth and brings it to her handler, who takes it from her. And once again Speedy runs away, back to the hidden person. After a comprehensive reward, the search continues and, with unflagging zeal, the same performance takes place. At the end of this search action, when she has found all three hidden people, Speedy still has enough energy left to play. I am convinced!

Figure 8.17 We have to train regularly in varying circumstances to keep our dogs at the same high level of performance.

Their Secret In the meantime, the chief joins us. “Isn’t that good?” he says. “So good, she is also working in avalanches and on rubble.” As if she wants to thank him for his nice words, Speedy comes to him and challenges him to play with her. She likes him, you can see that immediately. And she is right, because the ball in the sock is already flying through the air. “In spite of her young age, she is already working at the level required of an operational dog,” he assures me. “We don’t want to make the mistake of going too fast. An actual mission would mentally be too far for Speedy, and that would be fatal for her training. She must enjoy her youth in full. We keep all our dogs young and playful as long as possible. This stimulates their willingness to search and work.” Aside from Speedy, there are, of course, more young dogs in training. The Golden Retriever Bazil and two young Malinois, Karma and Igor, also demonstrate their work. They all show good work and they show too that they enjoy it. Karma also works with a bringsel, but when Igor reaches a victim, he begins to bark. My reaction to this shows on my amazed face. “Dogs that bark on their own are, of course, allowed to ‘speak’ at a hidden person.” Oh yes, that’s true. That is their secret: adjusting the method to the dog!

Rubble Search

Technology has tried to copy the excellent nose of the dog, and all sorts of equipment has been developed to try to trace people beneath rubble or dirt. However, this sensitive equipment is useless in the rubble of a major earthquake. Because of the inevitable dust, vibrations, noise, and electromagnetic fields that surround excavating machines, this detection equipment is easily disrupted. To search with this equipment, all rescue work has to stop in the surrounding area. This interruption is unacceptably impractical. The dog’s nose is irreplaceable. A correctly trained search and rescue dog is not distracted by the surrounding activity, not even by spectators or other crews working in the disaster area. The training of search and rescue dogs is more necessary now than ever. Many victims, particularly after major earthquakes, owe their lives to the work of search and rescue dogs and handlers. Trapped People Earthquakes are not the only problem requiring search and rescue dogs. People can go missing in difficult or inaccessible terrain all over the world. A correctly trained search and rescue dog can be ready to track down a human in many emergency circumstances, such as an airplane or train disaster, where people may lie between the pieces of wreckage, or a collapsed building after a gas explosion. No country should neglect training search and rescue dogs. Where the government does not take care of it, private initiatives should step in to train reliable dogs and handlers. Search and rescue dogs have to search very intensively for the odor of people who are trapped beneath rubble or covered by a variety of materials. The dogs can’t be diverted by anything or anyone—they have to work in almost every terrain and under almost all circumstances. A search and rescue dog has to communicate to its handler that it has found a victim by indicating the place where the highest odor concentration—the scent clue—comes out of the rubble. The handler must recognize, by the way the dog behaves and gives its alert, whether the victim is still alive or already dead.

Figure 9.1 It is important that dogs learn to work independently and at a distance from their handlers.

Types of Alert For a reliable alert, it is important that the dog has a well-developed drive to find people. As shown in earlier chapters, the dog can develop a search drive for people with training that uses the hunting drive complex.

An alert always has to be chosen to suit the behavior of the dog and has to fit the dog’s character. The most important alerts used by search and rescue dogs working in rubble include the following: • Barking • Bringsel • Recall • Pawing • Behavior and postures Barking Dogs that bark easy on their own may begin to bark at a scent clue. This barking often happens because the dog is irritated when it can’t penetrate to the victim quickly enough. Training the barking alert is described in Chapter 8, “Wilderness Search.” Barking by itself is not enough as an alert for a real mission; the dog has to indicate the place of highest human odor concentration coming out of the rubble by pawing, scratching, or putting its nose in the rubble. Bringsel The bringsel alert, typically used in area searches, can cause problems if it is also used on rubble with the same dog. Trained to use a bringsel in a wilderness search, a dog should only pick up its bringsel when it makes contact with a victim. In rubble, that contact doesn’t often happen. Upon finding the scent clue for a person covered by rubble, the dog must give an alert without contact with the victim. If the dog then learns in a rubble search to alert at human odor without contact, there is a danger that it will begin alerting at the odor of other searchers during a wilderness search. In short, if you use the bringsel alert in the wilderness search, you cannot use the same alert in a rubble search. The bringsel alert is very useful with dogs that like to retrieve, but as with barking, the bringsel alert by itself is not enough as an alert for a real mission—the dog has to indicate exactly where the highest human odor concentration is coming out of the rubble by pawing, scratching, or putting its nose in the rubble. Recall With the recall alert, the dog walks back and forth quickly and directly between the handler and the scent clue spot of a victim, thereby leading the handler to that spot. The dog uses a special behavior towards its handler to show that it has found the odor of a victim beneath the rubble. Training the recall alert is described in Chapter 8, “Wilderness Search.” As with barking and the bringsel alert, for a real mission the recall alert must be accompanied by the dog’s pawing, scratching, or putting its nose in the rubble to indicate exactly where the highest human odor concentration is coming out of the rubble. Pawing A dog will scratch in an attempt to penetrate the rubble in the spot where the highest concentration of odor is emanating. In conjunction with this, we sometimes see the dog biting stones, wood, or metal to pull it out of the rubble. This pawing should not be confused with the so-called “orientational scratching,” by which the dog, to further convince itself of the odor, scratches away at some rubble with its front paw. The dog does this to open “odor canals” in the rubble. Pawing can also appear in combination with barking. Some people are afraid dogs will injure themselves by scratching in the rubble, but our experience is that this rarely happens. Dogs can judge how strongly they can use their paws. This behavior is especially important on missions where dogs work many days in a row and become tired—sometimes the only alert you see in the end is the scratching at the scent clue. Behavior and Postures The most important behavior is the dog being strongly interested in a certain place in the rubble and refusing to leave the spot. Even if it then walks away, it is often just going to get a breath of fresh air outside the area—even sometimes also outside the rubble area. Then the dog returns on its own, searching for and alerting at the spot with the highest odor concentration. It is also easy to see from the dog’s body expressions that it has found something. We can see it in the dog’s walk, body posture, ear stance, tail wag, and so on. The dog may also sit or lie down at the location of a strong human odor. By itself this alert is not enough. The dog has to be driven to indicate the scent clue spot of a victim more clearly by pawing or scratching in the rubble or putting its nose in the rubble. Natural Instincts For safety reasons, it is essential that a search and rescue dog stay in place when it is commanded to lie down. But the following example clearly shows that we have to stay aware of our dog’s communication at all times during a mission. After the 1980 earthquake in Italy, a search and rescue dog handler brought his dog to one of the houses still standing. The house was investigated and was shown to be safe. It was very cold, it was raining, and the dog had searched for a long time. To give his dog some shelter and rest, the handler laid him down in the house and went off with some rescue workers. However, after a few minutes the dog came to his handler, although this experienced search and rescue dog normally wouldn’t have moved from his place. At first the handler was irritated, but then he realized that something exceptional must have happened. He went back to the place where he had laid down his dog. On the spot where the dog had been lying, there was a big crack in the floor. There had probably been a tremor, which had gone unnoticed by the people, but the dog felt it, and as a result, left his position in the now unstable building. Value your dog’s instincts. Training Rubble Search Dogs don’t search for people buried in rubble out of humanitarian motives—dogs don’t know charity in that sense. While searching, they are using natural drives we have channeled in a direction that is useful to us. For the dog, finding the human is necessary only to get its sock toy. Because we involve ourselves as handlers in the whole event, and are offering the toy to the dog so that it can work out its drives, teamwork between the handler and dog develops, something that is necessary during lengthy search missions. Step 1 First build the connection between the dog and its toy—for our purpose always the tennis ball in the long sock—to get a dog with a strong drive. We also teach the dog to walk over the rubble, so its full concentration can be directed to the alerts and, in later steps, to searching. Step 2 Now start connecting the sock toy to human odor by teaching the dog that in the rubble it always gets the sock toy from a human. To train this connection, let the dog see a helper disappearing into an easy-to-reach hiding place. Place your backpack at the edge of the rubble area and stand with the dog about ten yards (10 m) from the hiding place. It is best to hold the dog with one arm around its neck and then with the other hand throw the sock toy over the ground to the helper in the hiding place. As soon as the helper gets the sock toy, stimulate your dog to go get it. The helper should immediately give the dog its toy. Let the dog play however it wants. Don’t take over the sock toy or interrupt the dog’s play with its prey. Only when the dog voluntarily involves you in the game should you play together with the dog and the sock toy and slowly walk toward the backpack. By the time the dog is done carrying and playing, you should be near the backpack. Now take the sock toy and give the dog some biscuits in return. You can now put the toy in a pocket or in your backpack. This ritual is repeated in the same way every time after the dog has searched. Be sure to take extra sock toys with you in the backpack, because some of them may get lost. And the dog biscuits, of course, are always stored in a closed container in the backpack.

Step 3 If everything goes well, we don’t throw the sock toy to the hiding place anymore. Instead, the sock toy is already at the helper before the exercise starts. The distance to the hiding place is still about ten yards (10 m), and the hiding place is still open. This training is not a search exercise, because we first have to build up the dog’s alert. On the way from the car to the rubble, talk to your dog and tell it what is going to happen. By the time you arrive, the dog will be excited to begin. Then, in front of the hiding place, keep the dog for a while to build up its excitement. If the dog doesn’t pay attention to the hiding place, the helper can call it or briefly show the sock toy to raise the dog’s excitement. Motivate the dog by voice and a throwing gesture of the arm to go to the helper to pick up the sock toy.

Figure 9.2 The success of training is highly dependent on the helper playing the correct role.

Step 4 Some cautious dogs don’t fully approach the helper in the hiding place. Sometimes the helper can try to entice the dog in, but it works better when you overcome this caution as a separate exercise. For this, the helper goes into the hiding place and entices the dog to come in. With cautious dogs, it is better when the helper doesn’t move or look at the dog and offers the sock toy on an outstretched hand, so that the dog can pick it up quietly. The helper should take care to not make unexpected movements. It is more important that the dog get the sock toy at the hiding place than to pay too much attention to how it gets there. Step 5 Now partially close the entrance to the hiding place using light materials adapted to the power and capacity of the dog. Close the hiding place with thin wood or small stones—absolutely no heavy stones and beams. First close about one quarter of the gap, so that the dog can easily go inside to pick up its sock toy. Keep in mind that the dog doesn’t have to search in this exercise, because these are still alert exercises. Don’t make the distance to the hole too large. If the dog hesitates, then you can first try throwing the toy into the hiding place. Step 6 Still working at the same hiding place, with the same helper and with the same ten-yard (10 m) distance, now close the hiding place halfway. If this change goes well, then close the hiding place by three-quarters. Continue to use light materials and keep the dog in the right mood on its way to the starting point. Release the dog to hunt with the throwing movement of your arm. Reward the dog only at the moment it picks up its toy in the hiding place. If you reward the dog too early, it may think it is being rewarded for pawing rubble, which can cause problems later. During longer search missions, the dog might start scratching somewhere without finding human odor, only because it wants to be praised. Step 7 Once you can almost close the hiding place, you can also increase the distance and let the dog approach the hiding place from various directions. The dog now has to use its nose more to achieve a result. Observe how your dog tries to get into the hiding place. Some dogs are pushers rather than scratchers. The hiding place has to be closed differently for each type of dog. For dogs that scratch, you can continue with the light materials used in earlier steps to close the hiding place. For dogs that try to push debris away with their head and body, you should close the hiding place with heavier materials, to force the dog to scratch. Step 8 Once the dog works well at step 7, start working at another hiding place that you first close by three-quarters and then more. Remember not to offer two changes for the dog at the same time. Start at a short distance and then vary the distance or the direction the dog will be sent. If necessary, throw the sock toy again to motivate the dog. As always, end with the carrying of the sock toy, playing, and prey sharing. Step 9 Now change the helpers and make more combinations of factors (terrain, hiding places, covering, etc.). Slowly build in heavier covering, so that the dog has to do more to find the odor. Also get the dog to track the odor of the same victim in one search repeatedly and frequently, with intervals in which the handler clears away some debris, and have the dog alert again on the same odor trace. This is how we work in the direction-showing alert of the dog. If this clearing away of rubble by the handler makes the dog lazy, then don’t clear it away, but just add some more pieces or shuffle it around. Step 10 With this training method we slowly build the dog’s connection between rubble and the activity of searching beneath it for human odor to reach the sock toy. Eventually you reach a point where the dog doesn’t know where the helper is in a rubble area. When it has smelled the odor of a helper, it has to dig through the rubble to reach the person and get the sock toy. This training method makes the dog use its nose intensively to locate people under the rubble. If you have taught this association, the dog knows what it has to do if it is shown a rubble pile. We can now make the circumstances more difficult and heavier, which will stimulate the dog more and more.

Step 11 After the dog is able to locate one victim, it will be taught to continue searching for more victims. That means it may get to play a bit less after getting its first sock toy before it is set to searching again. Step 12 Because of the greater depths to which helpers now can be found beneath the rubble, and the extensive work of salvaging, we use a smuggling trick to give the sock toy to the dog. After the dog has alerted on a spot, its handler will push the dog aside carefully, so that the dog can’t see what the handler is doing. The handler will lay the dog’s sock toy under a few small stones in the spot where the dog has alerted. In that way the handler “smuggles” the sock toy into the scent cone of the victim, and after that gives the dog the opportunity to search again to get to its sock toy. Step 13 It is also important that the dog learn to search the rubble area systematically under the direction of the handler. Don’t allow it to run from the left to the right over the rubble, but press it to search a certain area first and after that go to the next bordering area. That way the dog learns how to search with direction from the handler.

Behavioristic Approach Why does the dog learn with this method? The natural talents of the dog allow us to activate the hunting drive complex and the play drive. So we see, for instance, that an unmoving sock toy is uninteresting for some dogs; other dogs bring it to the handler to play, and others shake it to death or try to bury it. All this behavior is inspired by revived drives. The sock toy, presented to the dog as living prey, is the motivation the dog is working for. The hunting behavior is a motivational source present in every dog. That’s why it is important that the handler, after the dog gets the toy, keeps in contact with the dog and stays involved until the prey sharing. For the dog the biscuits are not that important, but the prey sharing ritual is. This way dogs stay enthusiastic about searching and can do this for hours. They want to work. We have tested our method extensively and have achieved great results in practice exercises, in search and rescue dog sports, and in the hard reality of actual missions. We have proven that this method stimulates and activates dogs, even during extreme operations, where sometimes searches go on for many days. Nowadays the behavioristic approach in training is popular. Many trainers use operant and classical conditioning to train search and rescue dogs, but our vision is that you still have to start from the instincts and drives of the dog, and you need to use all the dog’s skills, capabilities, and intelligences. Intelligence In dogs we distinguish between three forms of intelligence: the instinctive, the practical, and the adaptive. By instinctive intelligence, we mean all hereditary skills and behavior. A prime example is the hunting drive: every puppy runs after a moving object.

By practical intelligence, we mean the speed with which, and the degree to which, the dog conforms to the desires of the handler—roughly said, how quickly and how correctly the dog learns the different exercises. This is the intelligence used in the behavioristic approach: in training through classical and operant conditioning. Adaptive intelligence can be divided into two abilities: learning proficiency, which means how quickly the dog develops adequate behavior in a new situation, and problem solving ability. This last is the dog’s skill in choosing the correct behavior to solve a problem it encounters. This is the intelligence we need in dogs searching in real missions. In our method the dog has the potential to develop and use its adaptive intelligence. Although many search and rescue dogs are still trained in a mechanical way, years ago we moved our training successfully in another direction. We are convinced that only happy dogs, unspoiled by faulty training, are able to work out all the complex and challenging tasks necessary during real missions.

Figure 9.3 Besides the helper in the hiding place, good helpers on the surface are also important in training search and rescue dogs. The helpers need to close the hiding place appropriately for each dog, depending on whether it is a “pusher” or a “scratcher.”

Figure 9.4 Why not adapt the method to the dog, rather than trying to adapt the dog to the method?

Case Study: Spitak Earthquake, Armenia, December 1988 Around noon on Wednesday, December 7, 1988, Armenia is hit by a huge earthquake. People run in panic to the street. Men, women, and children are trapped in the rubble of their own houses, factories, and schools—desperate people in a world full of chaos. The Search and Rescue Dog Organization of Holland (RHH) travels to the area at its own risk and costs. A diary of this ten-day mission offers clear evidence that it is absolutely necessary to bring well-trained search and rescue dogs and their handlers to a disaster area as soon as possible. Only then is there a reasonable chance of survival for buried victims. Thursday: The reality is brought home to the world. Estimates on the number of dead have climbed to 50,000 and later even 100,000. The number of injured is ten times more. I call the Soviet Embassy in The Hague and offer the services of our search and rescue dogs. They promise me to send a message to Moscow and I wait for their answer. Friday: Starting early in the morning, I try to find a way to set up a mission for our search and rescue dog teams using my foreign contacts and via the Soviet Embassy, which has to organize the visa to Armenia for us. I call the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in The Hague, but they say we have to wait until the USSR asks for our help. To me, that is as if someone has been in an accident and lies hurt on the street, and the bystanders have to wait until the victim asks for an ambulance! Monday: Valuable days have been lost and there is still no progress. We start to think it is hopeless. Suddenly, we get the news that the Soviet Embassy has asked for our help. I can’t believe my ears. For a short time we consult with each other, but because we rescued a living victim out of the rubble after fourteen days in Italy in 1980, we don’t doubt for long and we decide: we go! Tuesday: On our way to Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport, I hear somebody on the radio say that yesterday in Armenia people were dug out of the rubble alive. Then I know: our mission with seven search and rescue dog teams and one physician is meaningful. We leave at 5:30 p.m. on a cargo plane via Moscow to Yerevan. With us is a cargo of thirty-two tons of blankets and medicines. Wednesday: The disastrous earthquake was exactly a week ago. So much time has been lost. At the Yerevan airport, a Bulgarian interpreter tells us that a rescue team waited here yesterday for ten hours for further transport. We take action, and one and a half hours later we leave in an old bus with our luggage and two interpreters, watched with amazement by the authorities, who didn’t expect so many surprises from the Dutch. Okay, they probably thought, the rowdies are gone now. Around noon, we reach Spitak. When we climb near a damaged monument to see the surrounding area, we are convinced: Spitak does not exist anymore! The city is one big rubble pile and everything big has been cleared away. About 20,000 people died under the falling rubble. The commander of the local government says that he has no need for search and rescue dogs in his town anymore. A little bit further we find a general who gives us permission to help in the villages outside the city. We drive our bus to Shirakamut, a village about six miles (10 km) from Spitak. This is where the epicenter of the earthquake was. I am dismayed when we approach the village. There’s not a structure standing anywhere. The people in the village are perplexed about our offered help. In all that time (a week), nobody has shown up to help the inhabitants. With their bare hands and some other simple equipment, they have searched in the rubble piles for their family members and neighbors. Almost everyone has been salvaged, including more than 200 bodies of children in the school building, formerly the pride of the area. As is customary with the Armenians, we get a warm welcome and are invited to take a place at the table set up near their campfire. Of course, we have to taste vodka they’ve made themselves and they share their scarce bread, bacon, and cheese with us. We cannot refuse, because they are so grateful that we have thought of their village. But they also tell us that we have to go to Leninakan (now called Gyumri), where the people need us urgently. On our way to Leninakan, we pass a large cemetery brimming with people. To our dismay we see dozens of people in old cars and on open trucks on their way to bring their nearest and dearest to their final resting place. In a passing station wagon with an open tailboard, a woman is hanging over a coffin, crying. I grab my camera, but I can’t take a picture. I can’t record the sadness, misery, and poverty around me. The cemetery is crowded. Everywhere people are digging or standing around a grave. It looks like a ghastly film, but it is the reality of Armenia. In the afternoon, when we enter Leninakan, I immediately discover that here, there is work for us! On the rubble piles people are searching desperately for victims. Also, here they have to work with their bare hands, because they do not have the right equipment. We immediately go to look for the commander of Leninakan. But when I meet him, he is sitting bowed over a map of the town, crying. I discover that the largest part of the map is shaded red. For me, it is clear: Leninakan, a town of almost 300,000 inhabitants, has been about four-fifths destroyed. In answer to my question of where we can work with our dogs, the man draws up his shoulders and looks sadly at us with a tear-stained face. I understand. He doesn’t know anymore where to begin. The disaster is beyond imagining. It is time for us to take the initiative. A friendly woman from the local government advises us to have a look at the shoe factory. Five hundred laborers were buried under the rubble, but the leader of the salvage team has no hope. The factory became a mass grave for almost the whole staff. Of the hundred dead bodies already salvaged, about twenty are lying beside the road on stretchers covered with plastic or other materials from the rubble. Large numbers of people are standing by the gate and waiting until family members are salvaged out of the rubble. Heartrending crying makes it clear that again somebody has recognized one of his dearest. Also, for him or her, rescue came too late. Bystanders help the family lay the dead person in a coffin. Family members have to transport their deceased to the cemetery on old trucks or even on a roof rack of a passenger car. I watch as helping hands come out the window of a passenger car to keep the coffin on the roof of the car—they couldn’t even find a rope to fasten the coffin with.

Figure 9.5 Families sometimes have to transport their deceased to the cemetery on the roof rack of passenger cars. (Leninakan, Armenia, 1988)

Later I even see dead bodies transported without coffins. Others can’t find nails to fasten the lid of the coffin. The tragedy is so large it can hardly be described. Of course, we are all deeply affected by the sadness that prevails here. But we do not allow ourselves to become paralyzed; we have to do the job! On the rubble of what once had been nice five-storey apartments opposite the shoe factory, I see people digging in the rubble. In the rubble pile to my right, neighbors are searching for a composer and his wife. On the left, a little old man with a sad face is digging for his daughter. We let our dogs search, and very quickly, we know where the composer is lying. His wife is more difficult to locate, because she is lying thirteen feet (4 m) deeper, beneath fine rubble. After that the missing daughter is found under concrete slabs. All three are dead, crushed under the enormous mass of rubble. Locating dead people isn’t a good experience for the dog either, but the reward and satisfaction of the handler makes them happier. In the middle of a public garden, our handlers set up on a spot that we later call the public garden bivouac. There the handlers and their dogs can keep themselves warm at a fire made of wood picked out of the rubble. My shoes are covered in mud—because of the damaged water works and sewers, the streets in Leninakan have a surface of mud at least two inches (5 cm) thick. The rain and snow have only added to the mess. Leninakan is at an elevation of almost a mile (1,500 m). During the day the temperature is reasonable, but at night it goes down to minus 4°F (-20°C). The clothes, materials, and experience we picked up during avalanche courses in Austria are to our advantage now. Dogs and people sleep that cold night in their tents, close to each other on the ground. Thursday: Jorge, our interpreter, comes back from reconnoitering and tells us that our help is needed at a few collapsed apartments. We search carefully in the heavy, dangerous rubble. At four points the dogs alert to dead people. We know that because the dogs always give a passive alert at dead bodies; the happiness they show when people are alive is then absent. As soon as a victim is salvaged, the search and rescue dog is once again set up on the same place, because victims are often found lying very close to each other beneath the rubble, which also happened this time. Two other handlers are searching with their dogs on a gigantic rubble cone beside the apartments. Here once stood seven-storey apartment buildings, of which nothing is left. According to our interpreters, we are now standing on the fourth floor, and the dogs are searching very well. Three dead people in a corner of what was a stairwell, then a baby in the bedroom, crushed in his cradle; and at the neighbors’ apartment, an older man is still half sitting in his chair. The dogs are all doing good work, and there we only find dead people. We also find a seven-year-old girl in a corner of a classroom. Survivors seem out of the question. Knock signals There is suddenly a change when a police car pulls up with flashing lights and stops beside us. Speaking quickly, the police officers tell us we have to come with them. On a rubble pile in town they have heard knock signals and urgently need the dogs to locate the victim. A few handlers jump into the little bus and we keep our dogs on our laps while the car drives away at high speed. We drive quickly through downtown Leninakan. My heart almost stops when I see what kinds of dangerous things the driver does to get through the busy traffic. We reach the site. From the top of an enormous rubble pile, people show us the direction to come on, and helping hands bring us to the right place. The rubble pile swarms with people. I try to make it clear that we need room for the dogs to search, and slowly people give us space. Too slowly, in my opinion. A moment later I discover that curiosity is winning out over common sense, because they are coming closer again. I know we can’t lose any more time. From the commander I have heard that the signals were indistinct but were absolutely coming out of this area. The rubble was once an apartment building with shops on the ground level. He estimates we are standing now on the second or third floor. The first dog begins to search the area. The crowd falls silent when they see the dog working. Breathlessly they follow, as we do, every movement of the dog. On two places the dog indicates dead bodies very clearly. We mark these places for a later search, but we want to find the source of the knocking first. The dog is working well, but it looks like there are dead bodies everywhere, something that’s understandable, with such a stench coming out of the rubble. I push my mask a bit more firmly on my face and follow with excitement the movements of the dog. Suddenly, I see his body become tense and his attention go to the right. With his ears pricked up he walks to a spot in the rubble. There he stands to sniff and then walks farther. I know almost for sure now. The dog is orienting himself to localize the exact place where the human odor is emerging the strongest. That’s why he has to smell and test every place. Still, the moment I’ve been waiting for so long comes as a surprise: the dog raises his tail, stretches his whole body, and smells in the rubble, even sniffing in a clearly audible way. He turns his hind end and keeps his nose deep in the rubble. He is beginning to scratch in the rubble enthusiastically and is even trying to bite the rubble away. That is the signal: he has found the scent clue of somebody who is still alive!

Figure 9.6 Suddenly the dog walks quickly to a spot in the rubble, puts his nose deep into the pile, and then starts to scratch the rubble away. (Leninakan, Armenia, 1988)

We watch as the dog tries to get deeper under the rubble. I see that the dog is looking at me for a moment. And the dog knows that I understand him. This is vital in a search and rescue dog team: namely, that a handler understands the dog and also that the dog understands its handler. But there is no time for daydreaming. There is work to be done. I discover that the rubble contains a lot of loose material that may be lying deep on a concrete slab of the next floor. Many square yards of rubble have to be removed with hard work. I reward my dog and take him to the edge of the rubble. Now a second handler and his dog have to search the area of the alert to see if the second dog will alert on the same spot. We need this confirmation, which only takes two minutes, before the serious work of salvage can start. We are happy to see that this dog is also scratching enthusiastically on the same place in the rubble. That’s where we have to dig. And we are lucky; there is a rescue team doing the salvage. The commander orders his people to clear the rubble. When there is a hole dug about one or two yards deep, the dogs are brought back in the hole to show the right direction for digging, because the scent clue does not always emanate from the spot right over the victim. Pieces of rubble often cause the odor to be redirected.

In the meantime, we search with our dogs where they earlier indicated dead bodies. But the dogs are less motivated; they’re more enthusiastic about helping to dig for the living victim. But there, we would only disturb. I’m asking my dog to locate the places of the first two alerts more accurately, and I see that he understands. He walks over the rubble, sniffing and indicating the places again. The second dog we use as a confirmation of the alerts is also telling us about a strong odor of dead bodies on those places. Skilful hands go to work. A bit later I see that in one place four dead bodies are dug out of the rubble and three in another place: a woman with a child beside her, both lying on their backs, and a man lying over them, protecting them with his arms. Trapped for Nine Days The commander asks us to come to him, and we see that after digging another yard and a half in the rubble, they have reached two concrete slabs. At a crack in the middle, the dogs are scratching enthusiastically again. Someone is lying right beneath them. But we lack the heavy equipment to lift the concrete slabs. The only possibility is to try to dig alongside the slabs and from there make a shaft inside. It is a difficult job, but it has to be done. The salvage team is working again, and from above an Armenian is trying to contact the buried person, but he is not successful. Suddenly, luck is with us. After digging on the side of the rubble and pulling away a big piece of concrete, the rescue team enters a large hollow room and, through a small opening, into a shop under the apartments. An approximately forty-year-old man is rescued. His eyes squint in the daylight when he is brought outside. For nine days he has kept himself alive with some vegetables and dripping rainwater. Immediately, nurses carry the man on a stretcher to the ambulance. He will survive! Before we know what has happened, the ambulance is out of sight and the people around us take our hands and pat us on the shoulders. The Armenian people are grateful to us and the salvage team, and that feeling is intense. Even though they are not relatives, friends, or neighbors of the victim, they still thank us profusely for our help. Austrian Army As we walk back to where the police car was once parked, I suddenly see at a distance a man in a red jumpsuit. I think I am really dazed now and I have to pinch myself in my arm to be sure. For sure, there in the distance stand our Austrian colleagues. I yell over the rubble and our Austrian friends turn around, amazed to see us. When they recognize me their hands go up in the air and we walk in each other’s direction. The greeting is so exuberant that bystanders are looking at us in amazement. I find out that they are on a mission with their search and rescue dogs together with the Austrian Army. The Austrian Army has a tent camp on the grounds of the Polytechnic School in Leninakan. The commanding officer of the army, who is standing nearby, invites us to cooperate and to live in their camp. Then we can use their facilities and they can use our dogs. A very good deal! That same night we move to the Austrian camp with our whole group. Friday: I hear that the Austrian Army has set up a coordination point in the center of Leninakan, where all requests for assistance are coming in. These requests will be sent by field telephone to our camp. We agree to work in three groups of search and rescue dogs: the Austrians with one group and us in two more groups. Coupled with every group are a complete army team of salvage workers with all the equipment, such as compressors and other salvage machines, a support group with equipment to catch sounds under the rubble, nurses, a physician, and a group-commander, who carries the walkie-talkie and maintains communication with the base camp. We’re transported in trucks and buses. This is efficient. As the groups are leaving, another group of soldiers is taking care of the toilets and the food. Later on we’ll be grateful for their preparation, because we will be working day and night!

Figure 9.7 We immediately reward the second dog for his good work. (Leninakan, Armenia, 1988)

Figure 9.8 Rescue came too late. When will authorities learn to send in well-trained search and rescue dog teams immediately? (Leninakan, Armenia, 1988)

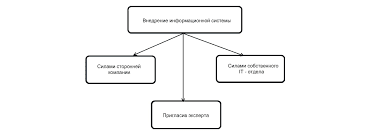

Our first action together takes us to the partly collapsed telephone exchange of Leninakan. One person is still missing there. Our dogs do their work again, and they alert at two places. In one spot the body of the missing man is found, and in another spot the body of another employee is salvaged. She had not been mentioned as a missing person! On our way back we pass makeshift huts and shelters built by the roadside. People stay close to the rubble where their families and property still remain buried. Around noon we go to a varnish factory, where our dogs search and locate. As a follow-up, we search a block of houses. An old man approaches us, showing us the picture of his daughter. In a corner both dogs give a passive alert. There they dig for her. In the meantime our dogs are already searching another house. There they also indicate the location of a buried victim and a block of houses a little fa   Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|