|

|

Children’s Language AcquisitionThe development of speech in children is summarized in Table 1.2. This development is the same for children throughout the world regardless of the language. French and Thai children babble between the ages of 3 and 6 months just as children who grow up in English-speaking countries do. Children who are language delayed because of mental retardation nevertheless still acquire language in the same order as children of average or above average intelligence. Table 1.2 - The Development of Vocalization

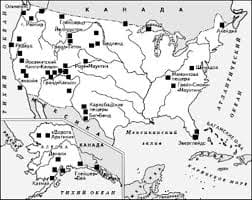

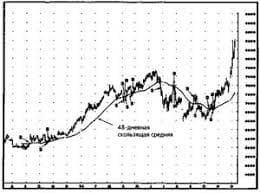

At birth, a baby is capable of producing sounds, none of which arc articulate or understandable. The infant is not yet equipped to produce speech. However, within a relatively short time, the baby refines vocalization until the first word is produced. Newborns are usually exposed to large amounts of stimulation: auditory, visual, and tactile. They quickly learn to distinguish human voices from environmental noises. By 2 weeks of age, infants can recognize their mothers’ voices. Between 1 and 2 months of age, infants start producing “human” noises in the form of cooing as they make sounds that have a vowel-like oo quality. They use intonation. Soon they can understand some simple words and phrases. Babbling About midway through their first year, babies begin to babble. This sign of linguistic capacity is indicated when they repeat consonant-vowel combinations such as na-na-na or ga-ga-ga. Unlike cooing, babbling tends to occur when the babies are not attempting to communicate with others; in fact, some babies actually babble more when they are alone than when people are present in the room with them. During babbling, babies do not produce all possible sounds: they produce only a small subset of sounds. Indeed, sounds produced early in the babbling period are seemingly abandoned as experimentation begins with new combinations of sounds. Research by Oller and Eilers (1982) has shown that late babbling contains sounds similar to those used in producing early words such as da-da-da. Semantic Development Young children first acquire meaning in a contentbound way, as a part of their experiences in the world that are largely related to a daily routine. Mother may say. “It’s story time,” but the youngster is already alerted by the picture book in Mother’s hand. “It’s time for you to take a bath” may not convey the message by itself; the time of day or evening and the presence of a towel, washcloth, and toys for the tub also give clues. Since the sharing of stories and baths are a regular part of the child’s daily routine, the young child has mapped out language in terms of observations. Around their first birthday, babies produce their first word. Typically, dada, mama, bye-bye, or papa are characteristic first words; they all have two syllables that begin with a consonant and end with a vowel. Because youngsters’ first words convey much meaning for them, most first words are nouns or names: juice, dada, doggie, and horsie. Verbs such as go and bye-bye, in this case meaning to go, quickly follow. Content-laden words dominate children’s vocabulary at this age, and they possess few function words such as an, through, and around. The use of one word to convey a meaningful message is called a holophrase. For instance, “cookie” means “I want a cookie.” First words may be overapplied. “Doggie” may refer to a four-legged animal with a tail. The neighbor’s pet cat would also qualify. Tony, age 14 months, lived next to a large cattle-feeding operation. Cow was one of his first words. When Tony saw a large dog or horse, he immediately identified the animal as a “cow.” Later, Tony refined his definition to refer only to female cattle as “cows.” Semantic development in children is interesting, for speaking and listening abilities can vary with the same child. Gina, an 18-month-old, was playing when her uncle pointed to a clock and asked, “What’s that?” Getting no response, he pointed to other objects in the room: the television set, the fireplace, and a table. Each time her uncle asked, “What’s that?” Gina merely looked at him. He decided she didn’t know the names of the objects. To test his theory, he tried a new line of questioning. He asked Gina: “Where’s the table? Where’s the clock? Where’s the fireplace? Where’s the television set?” Each time, Gina pointed to the correct object. Gina’s listening vocabulary exceeded her speaking vocabulary. In the next few months, she began using the names of the same objects in her speaking vocabulary, as the objects became more important to her conveying of messages. Vygotsky argued that young children initially use language only as a tool for social interaction. Later, they use language both in talking aloud during play and in verbalizing their intentions or actions. Telegraphic Speech After producing their first word, children rapidly develop their vocabulary, acquiring about 50 words in the next 6 months. At this time, children begin putting words together to express even more meaning than that found in a single word. In this way, children convey their thoughts, but they omit function words such as articles and prepositions. Brown and Fraser (1963) call these two-word utterances telegraphic because they resemble telegrams that adults would send. The limited number of words in telegraphic speech permits children to get their message across to others very economically. For instance, Sarah, age 20 months, says, “More juice” instead of, “I want another glass of juice.” The resultant message is essentially the same as the more elaborate sentence. Overgeneralization Young children acquire the grammatical rules of English, but often they tend to overgeneralize. For example, a 3-year-old may refer to mouses and foots rather than mice and feet. Comed may be substituted for came and, similarly, falled for fell. Such overgeneralization indicates evidence of the creativity and productivity of the child’s morphology because these forms are neither spoken by an adult nor heard by the child. In early childhood, children tend to invent new words as part of their creativity. Clark (1981, 1982) observed children between the ages of 2 and 6 years and found that they devised or invented new words to fill gaps in their vocabularies. Clark found that if children had forgotten or did not know a noun, the likelihood of word invention increased. Pourer was used for cup and plant-man for gardener in such instances. Verbs are often invented in a similar fashion, yet the verbs tend to evolve from nouns the children know. One 4-year-old created such a verb from the noun cracker when she referred to putting soda crackers in her soup as “I’m cracking my soup”. Children often substitute words that they know for words that are unfamiliar to them. A 3-year-old was taken by her grandmother to see The Nutcracker. After intently watching the ballet for a period of time, the child inquired, “Is that the can opener?” Children tend to regularize the new words they create, just as they overgeneralize words they already know. Thus, a child may refer to a person who rides a bicycle as a “bicycler,” employing the frequently used – er adjective pattern rather than the rare, irregular -ist form to create the word bicyclist. Semantic development occurs at a slower rate than do phonological development and syntactic development. The grammar, or syntax, of a 5-year-old approaches that of an adult. The child can actually carry on a sensible conversation with an adult. There are only a few grammatical patterns, such as the passive voice and relative clauses, yet to be acquired at this age. By age 4, a child understands all of the sounds in a language; however, the child may be 8 years old before he or she is able to produce the sounds correctly. For example, Jeff, age 3 ½, was going shopping with his mother and her friend Penny. While they were waiting for his mother to get ready, Penny noticed that Jeff had a wallet and some money. She asked Jeff what he planned to buy. Jeff said, “A purse.” “A purse?” Penny asked. To this question, Jeff insisted. “No, I want a purse.” Since the boy seemed to enjoy playing with trucks and cars, Penny was quite confused so she changed the conversation. At the shopping mall, Penny volunteered to help Jeff with his shopping. She asked Jeff to show her what he wanted to buy, thinking perhaps a carrying case for miniature cars was what he had in mind. Jeff led her to a large display of blue, red, and white things in the department store. Penny smiled and said, “You want a Smurf!” Jeff beamed, “Yes, I want a purse.” Jeff obviously could distinguish the difference between the words Smurf and purse when someone else said them, but the words sounded identical to him when he produced them.   Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|