|

|

Table 6.1 - The cooperative principle (following Grice, 1975)

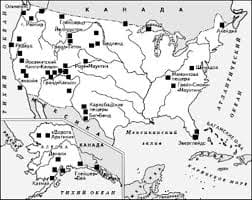

It is important to recognize these maxims as unstated assumptions we have in conversations. We assume that people are normally going to provide an appropriate amount of information (unlike the woman in (2)); we assume that they are telling the truth, being relevant, and trying to be as clear as they can. Because these principles are assumed in normal interaction, speakers rarely mention them. However, there are certain kinds of expressions speakers use to mark that they may be in danger of not fully adhering to the principles. These kinds of expressions are called hedges. Hedges. The importance of the maxim of quality for cooperative interaction in English may be best measured by the number of expressions we use to indicate that what we’re saying may not be totally accurate. The initial phrases in (3a.-c.) and the final phrase in (3d.) are notes to the listener regarding the accuracy of the main statement. 3. a. As far as I know, they’re married. b. I may be mistaken, but I thought I saw a wedding ring on her finger. c. I’m not sure if this is right, but I heard it was a secret ceremony in Hawaii. d. He couldn’t live without her, I guess. The conversational context for the examples in (3) might be a recent rumor involving a couple known to the speakers. Cautious notes, or hedges, of this type can also be used to show that the speaker is conscious of the quantity maxim, as in the initial phrases in (4a.-c), produced in the course of a speaker’s account of her recent vacation. 4. a. As you probably know, I am terrified of bugs. b. So, to cut a long story short, we grabbed our stuff and ran. c. I won’t bore you with all the details, but it was an exciting trip. Markers tied to the expectation of relevance (from the maxim of relation) can be found in the middle of speakers’ talk when they say things like ‘Oh, by the way’ and go on to mention some potentially unconnected information during a conversation. Speakers also seem to use expressions like ‘anyway’, or ‘well, anyway’, to indicate that they may have drifted into a discussion of some possibly non-relevant material and want to stop. Some expressions which may act as hedges on the expectation of relevance are shown as the initial phrases in (5a.-c), from an office meeting. 5. a. I don’t know if this is important, but some of the files are missing. b. This may sound like a dumb question, but whose hand writing is this? c. Not to change the subject, but is this related to the budget? The awareness of the expectations of manner may also lead speakers to produce hedges of the type shown in the initial phrases in (6a.-c), heard during an account of a crash. 6. a. This may be a bit confused, but I remember being in a car. b. I’m not sure if this makes sense, but the car had no lights. c. I don’t know if this is clear at all, but I think the other car was reversing. All of these examples of hedges are good indications that the speakers are not only aware of the maxims, but that they want to show that they are trying to observe them. Perhaps such forms also communicate the speakers’ concern that their listeners judge them to be cooperative conversational partners. There are, however, some circumstances where speakers may not follow the expectations of the cooperative principle. In courtrooms and classrooms, witnesses and students are often called upon to tell people things which are already well-known to those people (thereby violating the quantity maxim). Such specialized institutional talk is clearly different from conversation. However, even in conversation, a speaker may ‘opt out’ of the maxim expectations by using expressions like ‘No comment’ or ‘My lips are sealed’ in response to a question. An interesting aspect of such expressions is that, although they are typically not ‘as informative as is required’ in the context, they are naturally interpreted as communicating more than is said (i.e. the speaker knows the answer). This typical reaction (i.e. there must be something ‘special’ here) of listeners to any apparent violation of the maxims is actually the key to the notion of conversational implicature. Conversational Implicature The basic assumption in conversation is that, unless otherwise indicated, the participants are adhering to the cooperative principle and the maxims. In example (7), Dexter may appear to be violating the requirements of the quantity maxim. 7. Charlene: I hope you brought the bread and the cheese. Dexter: Ah, I brought the bread. After hearing Dexter’s response in [7], Charlene has to assume that Dexter is cooperating and not totally unaware of the quantity maxim. But he didn’t mention the cheese. If he had brought the cheese, he would say so, because he would be adhering to the quantity maxim. He must intend that she infer that what is not mentioned was not brought. In this case, Dexter has conveyed more than he said via a conversational implicature. We can represent the structure of what was said, with b (= bread) and c (= cheese) as in (8). Using the symbol +> for an implicature, we can also represent the additional conveyed meaning. 8. Charlene: b & c? Dexter: b (+>NOTc) It is important to note that it is speakers who communicate meaning via implicatures and it is listeners who recognize those communicated meanings via inference. The inferences selected are those which will preserve the assumption of cooperation. P. 45-46: Conventional Implicatures In contrast to all the conversational implicatures discussed so far, conventional implicatures are not based on the cooperative principle or the maxims. They don’t have to occur in conversation, and they don’t depend on special contexts for theirinterpretation. Not unlike lexical presuppositions, conventional implicatures are associated with specific words and result in additional conveyed meanings when those words are used. The English conjunction ‘but’ is one of these words. The interpretation of any utterance of the type p but q will be based on the conjunction p & q plus an implicature of ‘contrast’ between the information in p and the information in p. In (8), the fact that ‘Mary suggested black’ (= p) is contrasted, via the conventional implicature of ‘but’, with my choosing white (=q). 9. a. Mary suggested black, but I chose white, b. p &<j (+>p is in contrast to q) Other English words such as ‘even’ and ‘yet’ also have conventional implicatures. When ‘even’ is included in any sentence describing an event, there is an implicature of ‘contrary to expectation’. Thus, in (9) there are two events reported (i.e. John’s coming and John’s helping) with the conventional implicature of ‘even’ adding a ‘contrary to expectation’ interpretation of those events. 10. a. Even John came to the party. b. He even helped tidy up afterwards. The conventional implicature of ‘yet’ is that the present situation is expected to be different, or perhaps the opposite, at a later time. In uttering the statement in (10a.), the speaker produces an implicature that she expects the statement ‘Dennis is here’ (= p) to be true later, as indicated in (10b.). 11. a. Dennis isn’t here yet. (=NOT p] b. NOT p is true (+> p expected to be true later) It may be possible to treat the so-called different ‘meanings’ of ‘and’ in English as instances of conventional implicature in different structures. When two statements containing static information are joined by ‘and’, as in [z6a.], the implicature is simply ‘in addition’ or ‘plus’. When the two statements contain dynamic, action-related information, as in [z6b.), the implicature of'and' is ‘and then’ indicating sequence. 12. a. Yesterday, Mary was happy and ready to work. {p &cq, +>pplus q) b. She put on her clothes and left the house. [p &cq, +>q afterp) Because of the different implicatures, the two parts of (11a.) can be reversed with little difference in meaning, but there is a change in meaning if the two parts of (11b.) are reversed. For many linguists, the notion of ‘implicature’ is one of the central concepts in pragmatics. An implicature is certainly a prime example of more being communicated than is said. For those same linguists, another central concept in pragmatics is the observation that utterances perform actions, generally known as ‘speech acts’. *** From: PAUL GRICE: fLogic and conversation* in P. Cole and J. L. Morgan (eds.): Syntax and Semantics Volume 3: Speech Acts. Academic Press 1975, page 48. Cooperation and Implicature I would like to be able to think of the standard type of conversational practice not merely as something that all or most do IN FACT follow but as something that it is REASONABLE for us to follow, that we SHOULD NOT abandon. For a time, I was attracted by the idea that observance of the CP [co-operative principle] and the maxims, in a talk exchange, could be thought of as a quasi-contractual matter, with parallels outside the realm of discourse. If you pass by when I am struggling with my stranded car, I no doubt have some degree of expectation that you will offer help, but once you join me in tinkering under the hood, my expectations become stronger and take more specific forms (in the absence of indications that you are merely an incompetent meddler); and talk exchanges seemed to me to exhibit, characteristically, certain features that jointly distinguish cooperative transactions: 1. The participants have some common immediate aim, like getting a car mended; their ultimate aims may, of course, be independent and even in conflict-each may want to get the car mended in order to drive off, leaving the other stranded. In characteristic talk exchanges, there is a common aim even if, as in an over-the-wall chat, it is a second order one, namely that each party should, for the time being, identify himself with the transitory conversational interests of the other. 2. The contributions of the participants should be dovetailed, mutually dependent. 3. There is some sort of understanding (which may be explicit but which is often tacit) that, other things being equal, the transaction should continue in appropriate style unless both parties are agreeable that it should terminate. You do not just shove off or start doing something else. But while some such quasi-contractual basis as this may apply to some cases, there are too Tany types of exchange, like quarrelling and letter writing, that it fails to fit comfortably.   Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|