|

|

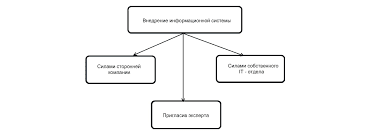

Figure 8.3 – Extract 3 Structure⇐ ПредыдущаяСтр 20 из 20

To show that discourse of this kind is not special to dog fanciers here are three other extracts: one from a mother helping her daughter with her homework, one from an academic, and one from a child aged 6; 4: D. The more tests you do, and the more different ways that questions arc put to you, the more you’re going to understand what the questions are about. So what you’re doing is sort of having a big bath of scientific language, and the more times you get into the bath the better you swim. And these kinds of tests are really good, because at school the teacher knows what she’s taught you, and she knows the words she’s used and everything else: these tests are sort of generalised, so there’s no way they can know exactly what you’ve learnt, but they know approximately what you should be learning about, so they ask you questions to test how much of the information has gone into your brain and been assimilated so that you can reproduce it even if the question is slightly different. E. The one comment I’d have has to do with her writing this up. The dissertation was written within the frame ‘these are the extant theories; let’s use these to derive hypotheses and get some data and cast them against the theories’, and that’s fine, but it’s also a limit, because it leads her for example not to ask such questions as the kind of thing I was pushing her on a little bit, what alternative meanings might be given to the class variable other than the socialization – it is true that in this literature the class variable is interpreted as a socialization variable, but that’s not necessarily the case if you start from the more general question of how can we explain radicalism rather than the more particular question of given the theories currently used to explain radicalism. F. When we ride on a train in the railway museum it’s an old-fashioned train but we call it a new-fashioned train though it’s old-fashioned because it’s newer than the trains that have only got one. - One what? - One driving wheel. But when we ride on a Deltic not in a museum we call it an old-fashioned train. It is often thought that sequences of conversational discourse like this are simply strings of ‘ands’. These extracts make it clear that they are not. Rather, they are intricate constructions of clauses, varying not only in the kind of interdependency (parataxis or hypotaxis) but also in the logical semantic relationships involved. These include not only three basic types of expansion – adding a new point, restating or exemplifying the previous one, or adding a qualification – but also the relationship of projection, whereby the speaker brings in what somebody else says or thinks and incorporates it grammatically into his own discourse. The clause complex is the resource whereby all this is achieved. It embodies the fundamental iterative potential of the grammar. This potential is found with words and groups as well as with clauses; for example, the long strings of nouns that we find in headlines, machine part names, and catalogues. But as a particular feature of spoken language its main contribution is at the rank of the clause. The natural consequence of the spoken language’s preference for representing things as processes is that it has to be able to represent not one process after another in isolation but whole configurations of processes related to each other in a number of different ways. This is what the clause complex is about. Two Kinds of Complexity It is wrong, therefore, to think of the written language as highly organised, structured, and complex while the spoken language is disorganised, fragmentary, and simple. The spoken language is every bit as highly organised as the written, and is capable of just as great a degree of complexity. Only, it is complex in a different way. The complexity of the written language is static and dense. That of the spoken language is dynamic and intricate. Grammatical intricacy takes the place of lexical density. The highly information-packed, lexically dense passages of writing often tend to be extremely simple in their grammatical structure, as far as the organisation of the sentence (clause complex) is concerned. Here is a passage from a philosophical work: We have defined the content of a scientific discipline by reference to three interrelated sets of elements: (I) the current explanatory goals of the science, (2) its current repertory of concepts and explanatory procedures, and (3) the accumulated experience of the scientists working in this particular discipline- i.e., the outcome of their efforts to fulfil their current explanatory ambitions, by applying the available repertory of concepts and explanatory procedures. So understood, of course, the ‘experience’ of scientists is not at all the sort of thing assumed, either by sensationalist philosophers like Mach, for whom the ultimate data of science were supposedly ‘sense-impressions’, or by physicalist philosophers such as the logical empiricists, for whom ‘scientific experience’ simply comprises straightforward factual generalizations. Rather, the experience of scientists resembles that of other professional men: for example, lawyers, engineers or airline pilots. (Stephen Toulmin, Human Understanding, vol. 1, Clarendon Press, Oxford. 1972. 175-6) The argument is of course complex; but the sentence grammar is extremely simple. There are some embedded clauses inside the nominal groups, but even taking these into account the passage does not display any of the kind of dynamic complexity that is regularly associated with natural, spontaneous speech. The complexity of the written language is its density of substance, solid like that of a diamond formed under pressure. By contrast, the complexity of spoken language is its intricacy of movement, liquid like that of a rapidly running river. To use a behavioural analogy, the structure of spoken language is of a choreographic kind. Of course, much conversation is fragmentary, with speakers taking very short turns; and here the potential for creating these dynamic patterns docs not get fully exploited. But the difference is not so great as it might seem, because what happens in dialogue is that the speakers share in the production of the discourse; so that although the grammar does not show the paratactic and hypotactic patterns ofthe clause complex in the way that those appear when the same speaker holds the floor, some of the same semantic relations may be present across turns. Transcribing Spoken Texts Why has it become customary to regard the spoken language as disjointed and shapeless? There seem to be three main reasons for this misunderstanding. One is that of the value systems of literate cultures, already referred to earlier. In an ‘oral’ culture (i.e. one without writing; to say ‘non-literate’ gives too much of a negative flavour), the registers of language which are highly valued, and the highly valued texts within those registers, are, obviously, spoken, since speech is all that there is. Once writing evolves, these texts are written down, because writing is felt to be a more reliable way of preserving them; which means that the value is now transferred to written language, and speech comes to be regarded as transitory and inconsequential. The second reason is that when people begin to transcribe spoken texts, in the age of tape recorders, they are so taken up with the hesitations and ‘false starts’ (the ‘crossing out’ phenomenon in speech), the coughs and splutters and clearings of the throat, that they put them all in as a great novelty, and then judge the text on the basis of their transcription of it. (Anyone who had learnt to listen to language would have been aware of these things without the aid of tape recorders, and they would have come as no great surprise; but unless you are trained as a linguist you are likely to process speech without attending to its sounds and its wordings – very naturally so, since this is what is necessary for survival.) But transcribing these features into writing is rather like printing a written text with all the author’s crossings out and slips of the pen, all the preliminary drafting mixed up with the final version – and then saying ‘Wow! What a mess’. (Imagine reading out a unedited manuscript in this way to someone who is illiterate – that is exactly the picture he would get of what written language is like.) The third reason seems to be that when philosophers of language began recording speech they started with academic seminars, because they were easiest to get at: there is a lot of talk, the interactants, since no great personal secrets were likely to be revealed. But this is just the kind of discourse that is most disjointed, because those taking part are having to think about what they are saying, and work out the arguments as they go along. The ordinary everyday exchanges in the family, the gossip among neighbours, the dialogue-with-narrative that people typically bandy around when sitting together over a meal or at the bar – and also the pragmatic discourse that is engendered when people are engaged in some co-operative enterprise – these tend to be much more fluent and articulated, because the speakers are not having to think all the time about what they are saying. If one’s aim is to bring out all the features that go into the planning of speech, then it is appropriate to transcribe it that way; this is like making a photocopy of an author’s original manuscript of a poem, or preserving all the stages that have gone into children’s composition – it is a special research task. But one would not use these documents to represent written language. In the same way, if one wants to understand what spoken language is like (as distinct from having some special research purpose of this kind), one looks for a form of transcription that is informative, in that it incorporates the systematic and meaningful properties of speech that ordinary writing leaves out, but that does not put in all the tacking and the bits of material that were left over in the cutting process. The following are some of the transcription systems for spoken English that are in current use; the references show where they may be found. 1. Survey of English Usage system R. Quirk & J. Svartvik, A Corpus of English Conversation (Longman, London, 1980). 2. D. Brazil, Pronunciation for Advanced learners of English. Student’s Book (Oxford University Press, 1994). 3. Conversational Analysis system H. Sacks, E.A. Schegloff & G. Jefferson, ‘A simplest systematics for the analysing of turn-taking in conversation’, Language, vol. 50, 1974. 4. Language Development Notation L. Bloom, Language Development: Form and Function in Emerging Grammars (MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1970). 5. Communication Linguistics system K. Malcolm, ‘Communication linguistics: A sample analysis’, J.D. Benson & W.S. Greaves (ed.), Systemic Perspectives on Discvourse (Ablex, Norwood, New Jersey, 1984). 6. Systemic-functional system M.A.K. Halliday, A Course in Spoken English: Part 3, Intonation (Oxford University Press, London, 1970). The last of these is the one that is being used here. It was originally devised for teaching spoken English to foreign students, but has since been used for a variety of linguistic and educational purposes. For very many purposes, however, there is nothing wrong with transcribing into ordinary orthography. This is easy to read and avoids making the text look exotic. The important requirement if one does use straightforward orthography is to punctuate the text intelligently. We have emphasised all along that writing is not speech written down, nor is speech writing that is read aloud. But the two are manifestations of the same underlying system; anf if the one is being represented through the eyes, or ears, of the other, it is important to use the resources in the appropriate way. If you read written language aloud, you do your best to make it sound meaningful. The same guiding principle applies when you write spoken language down. V. Further Reading From: G. Leech, E. Finegan. The Grammar of Conversation/Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English, L: Longman, 1999. P. 1040-1042: An example of conversation Before going further, we present a conversational extract (labelled ‘Damn chilli’) which illustrates many typical grammatical features of conversation. It will be used as a sample from which to exemplify such features in the functional survey which follows. From the transcription, it is not always clear what is occuring among the interlocutors, in spite of the relatively straightforward syntax and vocabulary of this extract. It will help to know something of the setting: a family of four is sitting down to dinner; P is the mother, J the father, and David (D) and Michael (M) are their 20-year-old and 17-year-old sons. D1: Mom, I, give me a rest, give it a rest. I didn’t think about you. I mean, I would rather do it. <unclear> some other instance in my mind. P1: Yeah, well I can understand you know, I mean [ unclear ] Hi I’m David’s mother, try to ignore me. D2: I went with a girl like you once. Let’s serve this damn chilli. M1: Okay, let’s serve the chilli. Are you serving or not dad? J1: Doesn’t matter. P2: Would you get those chips in there. Michael, could you put them with the crackers. J2: Here, I’ll come and serve it honey if you want me to. P3: Oh wait, we still have quite a few. D3: I don’t see any others. P4: I know you don’t. D4: We don’t have any others. P5: Yes, I got you the big bag I think it will be a help to you. J3: Here’s mom’s. M2: Now this isn’t according to grandpa now. P6: Okay. M3: The same man who told me it’s okay <unclear> P7: Are you going to put water in our cups? Whose bowl is that. M4: Mine. P8: Mike put all the water in here. Well, here we are J4: What. P9: Will y’all turn off the TV J5: Pie, I’ll kill you, I said I’d take you to the bathroom. P10: Man, get your tail out of the soup – Oh, sorry – Did you hear I saw Sarah’s sister’s baby? M5: How is it? P11: She’s cute, pretty really. (AmE CONV) This dinner table interaction touches on several seemingly unrelated topics. Reference is made not only to the dinner and its accompaniments (e.g. water, chilli, crackers, cups, bowl) and to other people (grandpa, Sarah’s sister’s baby) and apparently to a household pet named Pie, but also to an imaginary situation in which P speaks (in P1), to switching off the television, to past meetings, etc.). Some lines are opaque out of context (e.g. No this isn’t according to grandpa now; Oh sorry; and Man, get your tail out of the soup). Even the interpretation of J ’s What (J4) can only be guessed at. The shared background information and the shared physical and temporal space required to fully understand this excerpt are considerable. In this respect, although the difficulty of making sense of it on the page may be unfamiliar and disorienting experience for many readers, the extract is typical of conversation.   Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|