|

|

From the book “History of the Church” by N. Talberg.Стр 1 из 18Следующая ⇒ The Schism of the Roman-Catholic Church From the book “History of the Church” by N. Talberg. Translated from Russian by Seraphim Larin. Contents:

Missionary activity of the Latins. Papacy and Monasticism. Papal Conflict With Emperors. Decline of Papal Power. Attempts to Curb Papal Authority. Church’s Secession in the West. Reasons that Prepared the Separation of the Churches. Beginning of the Separation. Final Separation of the Churches in the 11th Century. Heresies and Sects in the West. Theological Directions in the West. New Dogmas in the Roman Church. Sects in the Roman Church in the 11th—15th Centuries. Reformation. General Dissatisfaction with the Roman Church. Reform Movements in Germany. Lutheranism. Roman-Catholic Church Politics. Guarding of Orthodox Faithful from Roman Propaganda. Latin Endeavors to Secure Holy Places in Palestine. New Papal Endeavors in Favor of Unionism. Interrelationship of Papacy and Catholic Governments. Religious Directions in the Roman Church. New Dogmas in the Roman Church. The Old-Catholics.

Addendum: The Jesuits. Introduction. History of the Jesuits. Conclusion.

Missionary activity of the Latins. T he missionary activity of the Roman church in the 11-15th centuries took on a character that is not proper for a Christian. The peaceful path of spreading Evangelical teachings by means of sermons and persuasion was forsaken. During the conversion of the unbelievers, the Roman church was more willing to allow the use of forceful measures — fire and sword. It was also not backward in sending her missionaries into those countries, where Orthodox missionaries were active, forcing them out and converting the newly Christened Orthodox faithful to the Latin faith. At the same time, they were also attempting to spread their teachings among the established Orthodox faithful, trying to convert them to their faith. The following methods were employed to spread Christianity throughout Europe: 1) A number of crusades of the cross to convert the Baltic Slavs (Wends); 2) Converting Prussians through force of arms — initially by the order of Prussian knights, and then by the order of German knights; 3) affirming Christianity, which had been established in the 12th century, by sword and flame of the sword-wielders in Livonia, Courland and Estonia, and 4) making Latvia into a Christian state through the marriage of the Latvian prince Yagailo with the successor to the Polish throne, princess Yadviga.Heathen Latvians were baptized through force, while Orthodox Latvians were subject to persecution. In Asia, the Latinos organized a variety of missions. They conducted propaganda among the Orthodox faithful, and endeavored to convert Muslims and heathens. They had no success among the Orthodox and the Muslims, and while they did establish a Christian congregation in the 13th century among the heathens (Mongols in China), it disappeared without a trace in the middle of the 14th century. After the discovery of new lands in western Africa and subsequently America, the Portuguese and Spaniards brought Christianity to these conquered lands. As a result of their brutal methods of converting the indigenous peoples, Christianity spread very feebly.

Papacy and Monasticism. Decline of Papal Power. A fter a century of stubborn struggle against the hostile house of Hohenstaufens, the papacy gained a complete victory over them. However, this very victory was the beginning of the fall of papacy. Charles of Anjou, obligated to the Popes for his sovereignty over Naples and Sicily, and having given them a lot of promises, aspired to occupy such a position in Italy that were occupied by German Emperors. The Popes were forced to undertake measures in order to weaken his authority. Pope Nicholas III (1277-80) concluded a union with German and Byzantine Emperors, and before his death prepared an uprising in Sicily against him, known as the Sicilian supper (?). Notwithstanding this, Charles succeeded in securing such an influence in Italy that in 1281, he insisted on the election of his subordinate Pope Martin IV (1281-85). However, the more dangerous opponent for papacy was the French king Philip the Fair (1285-1315). He rejected the papal right, established by Popes, to interfere in secular matters of other states. He delivered the first savage blow against Boniface VIII (1294-1303). Philip was at war with England. The Pope offered himself as a mediator, which Philip rejected, not wanting any interference from the Pope. The Pope became indignant, having learned that in order to cover his military expenses Philip had levied taxes on the French clergy, In 1296, the Pope issued a bull (without naming Philip), in which he threatened excommunication from the church to all laymen that are applying the taxes on the clergy, and all the clergy that are paying such taxes. The Pope replied by forbidding the export from France of all precious metals. As a result, the Pope began losing his income from France, and because of this, he agreed to concessions. The clergy was not forbidden to make voluntary donations for the state’s needs. A compromise was established, and Philip even accepted the Pope’s offer of mediating in his talks with the English king. However, it was soon discovered that in the role of adjudicator between the two, the Pope was supporting the English king. Hostilities renewed and the struggle between Philip and Boniface reached extremes. In 1301, because the papal legate spoke to the king so rudely, he had him arrested, ignoring the Pope’s demands to have the matter dealt with in Rome. The Pope wrote indignantly to the king: “Fear God and preserve His commandments. We wish you to know, that in spiritual and temporal matters, you are subordinate to us… We regard those who think otherwise as heretics. “ In another letter, he offered Philip to come to Rome with the French clergy — or an authorized body — in order to explain these matters. Philip burned both letters and replied: “ Let your immense stupidity know that in temporal matters, we are subordinate to no one… We regard those who think otherwise as insane.” In 1302, Philip convened an assembly of deputies from all classes of society, who expressed the same opposition as the King’s to the Pope, and triumphantly declared that the king received his crown directly from God and not the Pope. The French clergy concurred with this. Boniface responded by calling a council in Rome and condemning the behavior of the French with a bull “unam Sanctam” (opening words), in which he developed with full determination, Gregory VII system. He declared: “Christ entrusted the church with two swords, symbols of two authorities — spiritual and secular. One and the other had been established for the benefit of the church. The spiritual authority is found in the hands of the Popes, while the secular one — in the hands of kings. The spiritual one is greater than the secular one, just as the soul is greater than the body. Consequently, just as the body is subordinate to the soul, so must the secular authority be in subordination to the spiritual one. Only under these circumstances can the secular authority serve the church beneficially. In case of abuse by the secular power, then the spiritual authority must try her. The spiritual authority cannot be tried by anyone. To separate secular authority from the spiritual one and recognize it as autonomous, means to introduce a dualistic heresy — manicheism. In contrast, to acknowledge the Pope’s total spiritual and secular authority, is to acknowledge the faith’s dogma.” Philip answered this bull by convening an assembly of government representatives, where the jurist Wilhelm Nogareaccused the Pope of many crimes, and proposed the king be authorized to arrest and try the Pope. Boniface couldn’t tolerate this; in 1303, he damned Philip, applied interdictions on France and dismissed the whole French clergy. Philip convened a third assembly. Here, his skilful jurists accused Boniface of simony and other crimes, even non-existing ones e.g. of witchcraft, and as a consequence of this, it was decided to immediately convene a council in Lyons so that the Pope could be tried and the king vindicated. Meanwhile, Wilhelm Nogare was entrusted to arrest Boniface and present him to the council. Nogare set forth to Italy; he was joined by another enemy of the Pope, a cardinal who was a descendant of Colonna and who was driven out of office when Boniface became Pope. When they arrived, they found the Pope in a small town of Anagni. In order to disarm his enemies, he met them in full papal regalia, sitting on his throne. However, ignoring his endeavors, they arrested him in his own house. They treated him so harshly that after being liberated by the townspeople 3 months later, upon his return to Rome, he went insane and died shortly thereafter (1303). Boniface’s successor, Benedict XI, realizing that his predecessor acted too brusquely, attempted to have a reconciliation with France. However, after 8 months in office, he died (1304). During the election of the new Pope, the cardinals were divided — those who had France’s interests at heart, wished to see a Frenchman occupy the papal throne, while those committed to Boniface’s interests — an Italian. Finally, the French bloc took the upper hand. The chosen Pope was an Archbishop Bertrand of Bordeaux, who took the papal name of Clement V (1305-14). Having an influence on the election, Philip the Fair secured an oath from the new Pope that he will revoke all of Boniface’s arrangements concerning him, denounce Boniface and destroy the Knights Templar. Fearing repercussions in Rome for his concessions to France, Clement decided to remain in France permanently by summoning the cardinals and confirmed his residency in Avignon. The Popes remained here up to 1377, and this nearly 70-year stay is known in history as the Avignon papal captivity. The Popes of Avignon, beginning with Clement V, became fully reliant upon the French kings and functioned under their influence. Despite this, the Avignon Popes strived to play the role of universal overlords — if not in France, then in other countries. However, they were not successful. Awareness of independence of secular powers from spiritual ones developed everywhere. Following France, the next protestations against papal pretensions emerged in Germany. The Popes sent ineffectual excommunications and interdictions — but they were ignored. In 1338, the German Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria, the dukes and electorates even decided to show that the secular power was independent of the spiritual one, by passing a triumphant act. Having declared that the papal pretensions of controlling the Emperors crown as being unlawful, they decided that future coronations will not require papal affirmation. The same thing was passed in the “golden bull” (1356) of Emperor Carl IV. During the Avignon captivity of Popes, England being totally enslaved by the Popes since the times of John Lackland, also liberated itself from their influence. During Edward III reign, feudal tributes to the Popes were terminated, as was the practice of sending appellations to Rome. Even in Italy, the power of the Popes weakened. Only in the church sphere were they formally acknowledged as overlords. Whereas in reality, neither the Pope nor his successors and legates had any influence on the running of the state.Adherents of the Pope invited them to return to Rome, fearing that if the Popes remained in Avignon, papal authority would be completely obliterated. The Popes themselves were well aware of this. Employing a mercenary force for his resettlement within the church dominion, Gregory XI (1370-78) finally moved his residence to Rome (1377), where he eventually died (1378). With his death, the Roman church experienced the beginning of the so-called Great Schism. The majority of cardinals in the papal curia were French, having come from Avignon. They insisted that the Pope be French while the Roman people demanded that he be a Roman. Eventually, an Italian was chosen as Pope — Urban (1379-89), a man of harsh and even cruel nature. The new Pope began his reign with trying to improve the morals of the clergy; this touched upon the cardinals. Insulted by this, the French cardinals seized the Pope’s valuables, left Rome declaring the election of Urban as invalid and elected their own Pope Clement VII (1379-94), who shortly thereafter settled in Avignon. Clement was recognized by France, Naples and Spain, while the other nations acknowledged Urban. Thus a dual authority appeared in the Roman church.

Reformation.

Wycliffe. The English theologian, John Wycliffe (1324-84) emerged with his reformatory ideas in the latter half of the 14th century. The situation was favorable to him. During the reign of Edward the III, the English government had begun to gradually free itself from papal tutelage, and therefore looked favorably upon its opponents. Wycliffe began in 1356 with the publication of his work “about the last days of the Church.” Then during the confrontation of (1360), between Oxford university and impoverished monks, he began to orally and in writing argue that monasticism was insolvent. When the government refused to pay the papal tribute, Wycliffe came out in defense of the government. This earned him a professorship and doctorate at Oxford university. In 1374, commissioned by the government and in the company of others traveled, he traveled to Avignon for talks with the Pope. Here, he came face to face with the corruptness of the papacy and upon his return, began to preach that the Pope is an “antichrist.” In his attacks, Wycliffe began to reject the priesthood, arguing that it’s not the consecration that is the basis of their right to control and celebrate Divine Services, but the piety of individuals. This gave the impoverished monks the opportunity to accuse him of heresy. In 1378, a court was convened by Pope Gregory the XI to judge Wycliffe. Due to the protection of the English government, he was found guiltless, having satisfied the court with his explanations. This coincided with the papal split. Wycliffe renewed his attacks and began to completely reject the bishopric authority. He proposed to re-establish the “apostolic Presbyterian order.” He fully rejected Holy Tradition, teachings on purgatory and indulgences. He recognized the Gospel as the only norm of religious doctrine. He regarded Chrismation as not essential, oral confession as a violation of conscience, proposing that an inner penitence before God is sufficient. In the Mystery of the Eucharist, he recognized Christ’s spiritual and not His actual presence. He argued about the necessity of having full simplicity in Divine Services, proposed the allowance of priests to marry, and abolish the monastic order, or at least regard the monks on the same level as laymen. In general, Wycliffe strove to limit all means of contact between God and man, and regarded salvation as being dependent upon the personal relationship between man and the Redeemer. He founded an order of pious men for the dissemination of religious teachings and Evangelical sermons to the people. He began to translate the Gospel into English. Once again persecutions re-commenced against him. In 1382, a council in London condemned 24 areas of his teachings as heretical. King Richard the II could protect only Wycliffe himself, who retired from Oxford to his parish at Lutterworth, where he later died. Shortly before his death, Wycliffe wrote a treatise in which he outlined his thoughts on reform. As a result, he was condemned at the councils of Rome (1412) and Constance (1415). He left followers not only from the ordinary people, but from the highest class of society. They were called heretical Lollards. Under papal pressure, the English government refused them sympathy, and even assisted the church in their persecutions against them and they soon lost their significance. However, Wycliffe’s ideas sent out deep roots in England, as in many other countries.

John Huss. John Huss was a professor of theology in a Prague university in Bohemia. While Wycliffe reached a point of rejecting a great deal that was significant in religion, Huss on the other hand, in revolting against the evil practices of the Roman church, remained firm on the basics of the church, and even more — he was a defender of the early Orthodoxy. He was born in 1369, in Husinec that was located in Southern Bohemia; he received his education in a Prague university, where from 1398 he taught theology. There was talk of regeneration of the church even in Bohemia. It was there in the 14th century that a desire arose for the restoration of early Orthodoxy, which was preached in that region by Saints Cyril and Methodius. Divine Services in Slavonic language and the partaking of Holy Sacraments under both guises, formed the foremost desire of the Bohemians. In occupying the professorial chair, John Huss became a passionate champion for church reform, in the sense of returning to her early Orthodoxy. In 1402, he took up the post of preacher in a Bethlehem chapel (private church). In his sermons in Slavonic language, he taught the people faith and life according to the Gospel, which in turn forced him to make sharp criticisms of the Catholic priests and monks. Familiarizing himself with Wycliffe’s writings, he sympathized with them, but did not share their extreme views. The upholders of Latinism began to accuse Huss of Wycliffe’s heresy. Shortly after, there was a confrontation. Two theologians — followers of Wycliffe — arrived in Prague and presented to paintings. One depicted Christ, wearing a thorny crown and walking with His disciples toward Jerusalem — the other, the Pope wearing a three-sided golden crown and walking toward Rome, accompanied by his cardinals. Discussions commenced with the Bohemians having one voice, while the Germans and Poles, three. Not sanctioning the Anglican split from the church, Huss expressed his opposition to papacy in a spirit maintained by Wycliffe. Impelled by their nationalism, the foreign professors were against Huss. In 1408, they compiled some conclusions, in which they condemned 44 of Wycliffe’s opinions. However, in 1409, Huss received a decree from king Wenceslas, which presented the Bohemian university members with the majority of voices. Soon after, the Bohemians with Huss as their head, commenced to decisively speak out against the Roman church. The archbishop of Prague then came out against Huss. He sent a report to Rome, which in 1410, replied with a bull, directing that all of Wycliffe’s works be burned and his followers be brought to trial. It was also forbidden for them to preach in private churches. Huss appealed to the Pope, pointing out the many truths in Wycliffe’s teachings; he continued to preach in the Bethlehem chapel. The Pope demanded his presence in Rome. Owing to the intercession of the king and the university, the Huss affair ended peacefully in Prague. Soon after, in organizing a crusade against his enemies, Pope John XXIII sent a bull to Bohemia in which he granted a full indulgence to all crusaders. Huss rose against it in sermons and articles, while Jerome of Prague burnt the Papal bull. They people were on their side: unrest began. In 1413, a new bull followed, which excommunicated Huss from the Church and carried an interdictum against Prague. Huss wrote an appeal to the Lord Jesus Christ Himself, hoping to find justice on earth. At the same time, he published an article titled “About the Church,” where he argued that a true church must consist of believers. As the Pope had digressed from the Faith, he was no longer a member of the Church and his excommunication is of no importance. However, the archbishop of Prague was successful in forcing Huss out of Prague. In 1414 the Council of Constance convened. As a result of his former appeals to the Ecumenical Council, Huss’s presence was demanded in Constance. Emperor Sigismund even issued him a protective edict. Having arrived in Constance, Huss had to wait a long time to be interrogated, after which he was immediately arrested. The Emperor didn’t wish to insist on his release. The Council was annoyed over Huss’s demand that they prove him wrong in his thinking, based on the Gospel. This was regarded as heresy. The Council only sought to curb the Pope’s arbitrary powers while viewing all other matters with a narrow point of view. The future of Huss was not determined immediately, because the Council was dealing with the matter regarding John XXIII. Interrogation of Huss took place in prison. After 7 months, he was summoned to the solemn sitting of Council so that his matter can be concluded. He continued to insist on being shown his errors, based on the Gospel. The Council recognized him as a heretic and condemned him to be burned at the stake. On the 6th July, 1415, Huss died at the stake. Jerome of Prague, who arrived with Huss, was also burned at the stake in 1416 after a lengthy incarceration. However, the reformist movement in Bohemia didn’t end. After Huss’s death, the Bohemians, who had supported Huss before and after the Council sitting, revolted en masse against the Roman Church. Huss’s followers (Husseites) — with his permission — introduced a dual Holy Communion. While the Constance Council rejected this as heresy, the Bohemians decided to defend this with force of arms. Many citizens and nobility joined the Husseites. John Zizka became their leader. He and 40,000 of his adherents fortified themselves on a mountain, which he named Tabor. In the Czech language, a fortified camp is called Tabor, hence they began to call themselves Taborites. They were the left-wing part of the Husseite movement. Their religious element was evident in divine services, where the clergy took confessions, preached and gave Holy Communion in two forms. They practiced brotherly, communal dining and strived to maintain moral purity. At the same time, nationalistic and social questions had immense significance within the movement. The Taborites aimed at eliminating German rule and establishing a self-sufficient and independent Czech nation. The lower classes were imbued with hatred toward the Catholic clergy, who lived in luxury while burdening them with tithes and taxes. As an example, the archbishop of Prague owned 900 villages and many towns, which equaled possessions those of a king. The Taborites, living in their mountain and harboring hatred toward the clergy and the affluent classes, destroyed many churches, and carried out many discreditable acts. Their ideal was a democratic republic, rejecting secular and spiritual hierarchy. When Wenceslas — king of Bohemia — died in 1419, the Bohemians refused to swear allegiance to the new emperor Sigismund, because he betrayed Huss. All of Bohemia upraise against him. Pope Martin V, sent a number of armed crusades against them, which achieved nothing. The Bohemians were successful in repelling these attacks. Victories of Procopius the Great -their second leader — created great fear among the bordering nations. This situation continued until the convening of the Basle Council in 1431, where it was decided to attempt a reconciliation between the Husseites and Rome. By this time the Husseites had divided into two parties. The more moderate party, which was against extreme views, agreed to the reconciliation under certain conditions — the retention of dual Holy Communion, sermons to be in their native tongue, the clergy denied of church possessions and that they be subjected to a stern church court. These Husseites were also called the “followers of the chalice” and Utraquists. The other Husseites — Taborites — having reached a stage of fanatic hatred, made additional demands of iconoclasm, abolition of Confession etc.. In response to an invitation from the Basle Council in 1433, the Husseites sent a delegation of 300 men. Prolonged meetings didn’t produce any results, so the Husseites departed for home. The Council sent a deputation after them with a compromise offer. The Council was prepared to the 4 demands of the Chaliceites, who in turn joined the Church. However, in 1462, Pope Pius II declared all these concessions as null and void. Following this, the Chaliceites performed the dual Holy Communion clandestinely. Even after Basle Council’s concessions, the Taborites remained irreconcilable enemies of the Roman Church. Having suffered a savage defeat in 1434 — from the Catholic forces — they were forced to calm down. Around 1450, the remaining Taborites formed a small order under the heading of b ohemian or moravian brothers, which renounced arms and strove to lead their lives according to the strict teachings of the Gospel. In the 16th century, it began to spread and achieved the same level of importance as other religious orders, which appeared after reformation.

Savonarola Attempts to bring about Church reform appeared even in Italy, close to the Papal throne. In Florence, a Dominican monk — Girolamo Savonarola — emerged as a Church reformer. He led a disciplined life but was a zealous and captivating individual. During his time, the so-called renaissance of the sciences and the epoch of humanism in Italy, began an intense study of ancient pagan classics among the Italians, which reflected destructively on their spiritual outlook. The mixture of pagan and Christian outlooks, brought society to a new classical paganism. Religious understanding was so entangled in Rome that Christ was often confused with Mercury and the Madonna with Venus. Religious ceremonies were performed in honor of Virgil, Plato and Aristotle. Even the cardinals and bishops viewed the Gospel as some sort of Greek mythology. The spread of unbelief, associated with the lowering of morals among the Popes, clergy and society in general, prompted Savonarola to take the path of reform activity. Jerome (Girolamo) Savonarola was born in 1425, in a town named Ferrara. He was a descendant of an ancient family of Padua. His grandfather was a renowned physician. His father was preparing Jerome for a medical career and tried to give him a comprehensive upbringing. Early in his life, the quiet and pensive youth displayed an ascetic beginning, a love for contemplation and a deep religious feeling. The then prevailing situation in Italy deeply distressed Savonarola. A combination of an unsuccessful romance and an attraction toward theological works, especially Thomas Aquinas, brought him to a decision to enter a monastery. In 1475, he fled secretly from the family home to a Dominican monastery in Bologna. There, he led a austere life, gave away his money, donated his books (leaving the Bible for himself) to the monastery, fortified himself against the excesses of the monastery and devoted his spare time to studying patristic heritage. It was here that he wrote his poetical work “About the fall of a church,” where he pointed out that people didn’t have their prior purity, scholarship or Christian love, and the main reason for that was the decadence of the Popes. The father superior entrusted him with teaching novices and to preach. He was sent to preach in Ferrara, then in Florence where he became celebrated as an erudite at the monastery of San Marco. Because his sermons were less successful, he left for a small township to improve this deficiency. He later captivated his parishioners with his sermons. In 1490, he was summoned to Florence by its governor, the renowned Lorenzo Medici. Once again Savonarola took up teaching in the monastery of San Marco. His fame as a preacher grew. The monastery used to swell with laymen that came to listen. In 1490, he delivered his famous sermon in which he expressed his firm opinion that it was imperative to renovate the Church immediately, otherwise Italy will be struck down with God’s wrath. He asserted that like the ancient prophets, he is just relaying God’s commands, at the same time he censured the corrupt morals of the Florentines, not being coy with his choice of words. Because some of his prophecies came true — death of Pope Innocent, invasion by the French king etc — his influence increased. His kind and sincere treatment of the brothers made him the monastery favorite, and in 1491, he was elected as father superior of San Marco. He immediately placed himself in an independent position with Lorenzo Medici, who was forced to take it into account. After his renowned sermon against the extravagance of women’s ornaments, they ceased to wear them to church. Often, under the influence of his sermon, merchants returned profits that they acquired unfairly. He declared: “The power of Italy’s sins are making me a prophet.” Through his writings, it can be seen that he was convinced in his “divine calling,” and the people believed in his prophecies. When Peter Medici became governor of Florence and the infamously immoral Alexander VI Borgia — Pope, Savonarola’s warnings became sharper. At one time — as a consequence of being banned to preach by the governor — he quit Florence. Upon returning, he undertook monastery reform. He sold monastery possessions, banned extravagance, and forced all the monks to work. In order to achieve preaching success among the heathens, Savonarola founded teaching chairs in Greek, Jewish, Turkish and Arab languages. Pope Alexander attempted to attract Savonarola to his side, at first offering him the archbishop’s seat of Florence, then a cardinal’s cap. However, rejecting these offerings from the pulpit, Savonarola started to fulminate against the papal dissoluteness. During France’s king Charles VIII entry into Italy and the expulsion of Peter Medici from Florence, Savonarola became its true overlord. He restored republican establishments and carried out a variety of political and social reforms. Through his proposal, the Great Council — reinstated anew — replaced the land tax with an income tax, and freed borrowers from their debts. Decisive measures were undertaken against usurers and money-changers. Savonarola proclaimed Jesus Christ to the Senior and to the King of Florence, while remaining in the eyes of the people as Christ’s chosen one. He also attempted to transform Florence morally. In 1494, a strong transformation was already noticeable: the Florentines began to fast, attend church, and the women stopped wearing expensive adornments. The streets resounded to the singing of Psalms instead of songs and only the Bible was read. Many eminent people isolated themselves in the monastery of San Marco. He nominated sermons during the hours of ballet and masquerades; the people flocked to him. Savonarola decreed that sacrilegists have their tongues torn out and the debauchers — burned alive. Inveterate gamblers were punished with huge fines. He had his own spies. The people on Savonarola’s side were common people, a party of “whites” that were called "weepers." The ones opposing him were called “the possessed” — followers of the aristocratic republican rule, and the “gray,” who supported Medici. In his sermons, Savonarola didn’t spare anyone and as a consequence had many enemies among the lay, as well as the clergy. On a number of occasions, preachers emerged opposing him; the Pope banned him from preaching. However, his fame spread beyond the boundaries of Italy. His sermons were translated into foreign languages, even in Turkish for the sultan. Strong intrigues were maintained by Peter Medici. Savonarola’s enemies turned the Pope against him, who invited him to Rome; but he refused to come due to illness, and continued his sermons of censure. The Dominicans, appointed by the Pope to examine the substance of his sermons, found no grounds to accuse Savonarola of heresy. The Pope, once again, tried unsuccessfully to offer him the purple robes of a cardinal. Enjoying a popularity, strengthened through the saving of Livorno that was besieged by the emperor — which was predicted by him and defended by his faithful “VALORI” — Savonarola decided to strike a decisive blow against “the possessed.” He organized a squad of boys who, barged into eminent homes to see if the 10 commandments were being fulfilled, ran around the city confiscating playing cards, dice, secular books, flutes, perfumes etc. after which there was a ceremonial burning of these items in the city square. Secular books on humanism and classical antiquities were irreconcilable enemies to Savonarola. He even argued about the evil of the sciences in general. A society of degenerate youths was formed, who tried to kill him. On the 12th May, 1497, having labeled the teachings of Savonarola as “suspicious,” Pope Alexander VI excommunicated him from the Church. However, Savonarola refused to submit to this command and issued “an epistle against the falsely obtained bull of excommunication.” At the same, he issued his work “ Triumph of the Cross,” where he defends the true Catholic faith and explains the dogmas and mysteries of the Catholic Church. On the last day of the carnival in 1498, Savonarola performed a triumphant liturgy and “the burning of the anathema.” The Pope demanded he stand trial in Rome so that he may be imprisoned; threatened the whole of Florence with an interdict and excommunication of everyone who listens to Savonarola. However, the latter continued to preach, arguing the essentiality of convening an ecumenical Council as the Pope may be in error. After the Pope’s second decree — "breve" — the Florence authorities, signoria banned Savonarola from preaching. On 18th of march 149, Savonarola bid farewell to the people. He wrote “A letter to the emperors,” in which he urged them to convene an ecumenical council so as to dismiss the Pope. The letter to the French king Charles was intercepted and ended up in the Pope’s hands. The Florentines were worried. In order to test the righteousness of Savonarola’s teachings, a “God’s trial” was appointed — trial by fire. This was a trap organized by Savonarola’s enemies — “the possessed” and Franciscans. On the 7th of April. Savonarola and a Franciscan monk had to walk through fires. However, this never occurred. Disillusioned in their prophet, the people started to accuse him of cowardice. The following day, the monastery of San Marco was besieged by an irate mob. Savonarola and his friends were imprisoned. The Pope appointed an investigative committee of 17 individuals, selected from the party of “the possessed.” Savonarola’s interrogation and abuse was conducted in the most barbarous manner. They abused him 14 times a day, forcing him to contradict himself; through interrogation and threats compelled him to acknowledge that everything he preached were lies and deception. Savonarola was still able to write a final work. At the request of his jailer, his last work “Guidance in a Christian life,” was written a few hours before his death on a cover of a book. On the 23rd of May 1498, in the presence of a large crowd, Savonarola was hanged and his body burned. Savonarola’s teachings were vindicated by Pope Paul IV (1555-59), while in the 17th century, a church service was created in his honor. However, his activities evoke divided opinions. Some idealize his honesty, candor and broad plans, and see him as a reformer that exposed the corruptness of the Church. Others argue that he lived with ideas of the middle-ages; that he didn’t create a new church, but retained a strong Catholic essence; that in emerging initially as a reformer, he intermingled politics into his work and appeared as a demagogue, which is what brought about his downfall.

The Old-Catholics. T he announcement of the dogma on the Pope’s infallibility provoked a protest of opposition, which quickly formed into an “old order Catholic Church.” It was established by Catholic theologians that didn’t recognize the new dogma. In Germany, this movement began immediately after the dogma was accepted in Rome. The main leaders of this movement were professors of theological studies from Catholic faculties in universities at Munich, Bonn and other cities. An especially outstanding individual among them was the dean of Munich university, the renowned Dallinger. Under his influence and guidance, in 1874 in Munich, a society was formed called “old order Catholics,” which did not recognize the Vatican council’s enactment's, and generally rejected the “ultra-montanism’s” theory on papacy. Following the formation of the society in Munich, other old order Catholic societies began to spring up in other German cities, like Cologne, Bonn and others. The learned theologians were hoping that their movement would be supported by the German bishops, being their comrades by profession and who had shown vigorous opposition to the acceptance of the papal dogma; however the bishops refused to create a rift with the Pope. The professors, accusing the new papal teaching as a contradiction to the Gospel and Christianity, received empathy and approval from the diverse classes of the population in various areas of Germany and Switzerland. They also received favorable attention on the part of Prussia, Wurttemberg, Baden-Hesse and several Swiss cantons (autonomous regions). An idea was formed about organizing the movement, committees and conferences began to form and their delegates appointed to the central committees and congresses. Developing slowly, the old order Catholic movement assumed the form of a positive religious denomination, became organized, formed religious communities in Germany and Switzerland and having received religious corporate rights, established its own churches. The dogma on the Pope’s infallibility is just an extreme expression and the end result of the papal system, both in teachings and rights, beginning approximately in the 9th century and developed over many centuries. The papal system brought with it the separation of Churches and distortion of canonical order of the Church, established on the beginnings of Apostolic tradition and legislation of the Ecumenical Church; she brought about the rift in Western Europe, where the opposition to the papal love of power was expressed through the formation of Anglican, Lutheran, Reform and Utrecht churches, as well as the appearances of many opposition movements. In the subsequent development of their protest against the Vatican dogma, the learned leaders of the old order Catholics should have also aimed at cleansing the Church of those strata -associated one way or another with this dogma — which have been introduced by the Popes. At the first congress, they in fact marked down such a program aimed firstly, toward the restoration of old Church canonical order among their Christian adherents; secondly, the cleansing of Christian teachings of aberrations and innovations, and the restoration of the dogmatic truths of the Ecumenical Church that existed in the first ten centuries; thirdly, to unite with the Orthodox Churches and faiths that existed in Western Europe. In 1871, at the first old order Catholic congress in Munich, rules governing the formation and organization of parochial communities were formulated. Every community had to have a priest, and for their ordination, a bishop was essential. An “episcopate committee,” formed in 1872 and made up of professors of theology, selected the former professor and priest Joseph-Hubert Reinkens as the bishop. Consecrated by the Utrecht archbishop Gool he swore an oath of allegiance to the Prussian king and government, and was recognized in Prussia, followed quickly by Baden and Hesse as being a worthy “bishop of the German old order Catholic Church.” The organization of the old order Catholic Church in Germany was worked out with his participation and direction. Its composite sections were — parochial communities, parishes with bishops and a synod. After the death of “REINKENS” (1896), his replacement was a former professor of philosophy, Theodore-Hubert Weber. The most success achieved by the old order Catholic movement was in Switzerland. Its substance is outlined in the “Utrecht declaration,” signed on the 24th September 1889 by bishops Reinkens and Gerzogand three other bishops of this Church. In it, the false teachings of the Popes are rejected. The old order Catholics emphasized that they were striving to preserve the old, unspoiled Catholicism. According to their convictions, such Catholicism represents itself as the Church of the Ecumenical Councils, when unity existed between East and West. This conviction led the old order Catholics to the idea of coming closer — and even restoring communion — with the Eastern Orthodox Church, as well as the Western Christian societies that recognized the Church beginnings of the Ecumenical Councils’ times. With this aim in mind, in 1874 and 1875, the leaders of the old order Catholics arranged two conferences in Bonn, called “friends of Church unity.” At these conferences, apart from the old order Catholics participating, there were representatives of theological study from Orthodox East — even from Russia, as well as spiritual individuals and theologians of Anglican and Protestant beliefs. The aim of the conference was to work out a basis upon which it would be possible to establish unity among all the Churches. However, notwithstanding the genuine desire for unity on the part of all the participants, and despite the fact that there was agreement on some points, these discussions did not bring the desired result in the ensuing period. At the Lucerne congress in 1892, a proposal was adopted for the old order Catholic bishops to enter into official relations with the Eastern Churches, and particularly with the Russian Church. On the 15th December 1892 in St. Petersburg, the Holy Synod directed that a commission be formed to determine the conditions and demands, which could be presented as a basis for discussions with the old order Catholics. The commission was chaired by Archbishop Anthony (Vadkovsky) of Finland. An accord didn’t ensue. The reason for this was because in recognizing the true Church as being that of the Church of Ecumenical Councils, the old order Catholics didn’t want to take that decisive of severing their ties with Catholicism and returning to the bosom of the Eastern Orthodox Church, which has preserved up to the present time, the pure beginnings and Traditions of the ancient Universal Church. E. Smirnoff sums up the old order Catholic movement with the following: “Strictly speaking, the old order Catholic’s successes (in the past and present) within the Roman Church have been insignificant. Because of their general indifference to religious questions, educated Catholics do not adhere to this party. Masses of Catholic people stand aloof from the old order Catholicism, because their spiritual guides, taking advantage of their lack of knowledge, are very skillfully able to sustain their loyalty to the papal Church. Catholic and Protestant governments treat old order Catholicism with indifference. Finally, as a result of vagueness in its tasks and aims, it couldn’t and cannot have great success in the West: having separated itself from papal Catholicism, it didn’t merge with Orthodoxy, and assumed a peculiar and indeterminate position among Christian communities. Generally speaking, results of the old order Catholic movement is a question of the future.”

Addendum:

The Jesuits. The Jesuits Introduction. History of the Jesuits. 1. Ignatius Loyola. 2. Loyola’s First Disciples. 3. Organization and Training of the Jesuits. 4. Moral Code of the Jesuits. 5. The Jesuit Teaching on Regicide, Murder, Lying, Theft, Etc. 6. The “Secret Instructions” of the Jesuits. 7. Jesuit Management of Rich Widows and the Heirs of Great Families. 8. Diffusion of the Jesuits throughout Christendom. 9. Commercial Enterprises and Banishment. 10. Restoration of the Inquisition. 11. The Tortures oft the Inquisition. Some Quotes: Conclusion.

Introduction. T he correct name of the body is the Society of Jesus. When Ignatius of Loyola proposed to found an organization, the Protestants of Germany and England had exposed the comprehensive corruption of the monastic orders, and those who advocated reform in Rome itself wanted the suppression of all Orders rather than the establishment of new. Ignatius had great difficulty in securing permission to found even a “Society,” whose members should take the usual vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience and live in communities without being classed as monks. Permission was granted in 1540 after years of intrigue and deceit — the followers of Ignatius in Rome were directed ostentatiously to serve the sick poor and quietly secure rich youths and the support of rich women — which left a permanent mark on the body. It was characterized also from the start by the martial spirit of the ex-soldier Ignatius and by its special consecration in the Pope's service as a regiment to fight heresy. Its activity was rightly called “Jesuitry” from the first. The vow of poverty, collective as well as individual, was prevented from interfering with the accumulation of wealth, which was a primary aim, by drawing a distinction between “colleges” and “houses of the professed” (equal to monasteries) and claiming that the former could acquire unlimited property. From the first also the characteristic Jesuit practice of spying on each other and tale-bearing was introduced and the vow of obedience was especially stressed. Nicolini mistranslates the Constitutions when he says that the Jesuit is “bound to obey an order to commit sin,” but the document is written (here at least) in such crude Latin that one might so interpret it; while in practice a Jesuit superior would always claim that it was his business to judge whether the act prescribed was sinful, and the appalling casuistry of the theologians of the Society would serve his purpose. The charge that they had in addition a secret Constitution (Monita Privata) is disputed. The Jesuits contend that the Polish ex-Jesuit Zahorowski fabricated or falsified the document. He may have tampered with it, but so many copies of the document were found in Jesuit houses when the Society was suppressed in the eighteenth century that it is widely accepted as genuine. Modern Jesuits, on the other hand, try to convince the world of their high character by describing their “Spiritual Exercises” — an intensive periodical course of religious training such as all monks and nuns have — but these spiritual orgies leave no more permanent impression on monks than “revival services” do on an American small town. One must judge the Society by its actual history and by the very grave charges against it which the Pope fully endorsed in suppressing it. The Jesuits may never have laid it down in the public gaze that the end justifies the means [see Ends and Means], but it is a platitude of their history that they always proceeded upon that axiom. The special privileges (such as the right of their colleges to grant degrees) which they wheedled from favourable Popes — some Popes hated them as bitterly as most of the monks and clergy have always done — enabled them to capture the universities, and through these and their colleges, to which they drafted the sons of the rich and noble whom they particularly cultivated, they prepared Catholic lands for the ghastly Thirty Years War against Protestantism, in which groups of them followed the armies and hung about the camps. Their system of education, for which their writers have secured a high and spurious reputation, was the narrowest and most vicious (especially in regard to history) in Europe. In order to maintain their influence in this respect they pressed their services as confessors of princes and nobles everywhere and connived at their vices. In France, in the time of Louis XIV, the King and all the leading ladies of the Court had Jesuit confessors — Louis had three in succession during the most corrupt seventeen years of his life — and there never was a more debased court. France had at first regarded them with just suspicion, but their leader, Father Manares (whom the Jesuits themselves had later to condemn for corrupt ways), won favour by “discovering” a (fabricated) plot of the Huguenots and prepared the way for the St. Bartholomew Massacre. In non-Catholic lands their propensity for melodramatic secrecy and picturesque or murderous intrigue had full rein. In England, even under “Bloody Mary,” they, as Burnet tells in his History of the Reformation (II, 526), overreached themselves by trying to secure all the confiscated monastic property, and after Mary's death their intrigues in disguise and their inspiration of plots soured Elizabeth's policy of toleration. They boast of a hundred Jesuit martyrs in the period that followed. In point of fact only five regularly admitted Jesuits were executed (for plots), and two saved their lives by turning informers. They swelled their list of martyrs by getting priests in prison to “join the Society” before execution. In Scandinavia they strutted in court-dress as ambassadors and even, disguised, taught Lutheran theology in Protestant universities. In India some lived for years as mystics of the Hindu religion, and there (and in China) they made “converts” by permitting (for which Popes repeatedly condemned them) a mixture of Hindu (or Confucian) and Christian ideas and practices, while they worked fraudulent miracles on the ignorant natives. In South America [see Paraguay] they made virtual slaves of and exploited their converts and raised great wealth by trade. Local bishops whom they defied and libeled, priests, and monks assailed Rome with complaints, and in 1656 Pascal opened the attack on them in Europe by the scalding charges, especially of lax principles and leniency to vice, of his famous Provincial Letters. The Popes repeatedly condemned their practices (1710, 1715, 1742, and 1744), but dreaded their power and vindictiveness. More than one Pope is said to have been poisoned by them, and we smile at the ingenuous Jesuit plea that we cannot prove it. But Europe had now begun to feel a power more subtle, yet more honest, than that of the Society — that of Voltaire — and the great statesmen who were his pupils moved against them. The Marquis de Pombal got them expelled from Portugal in 1759. Choiseul exposed their trickery and their vast wealth in France and secured their expulsion (1764). Count D'Aranda had them suppressed in Spain (1767), and Tannucci in the Kingdom of Naples. A tense and dramatic struggle now proceeded at Rome, the Jesuits using every device in their large repertory to avert the suppression which the Catholic monarchs demanded, but in 1773 Pope Clement XIV, in the Bull Dominus ac Redemptor Noster, abolished the Society “for ever.” The charges against the Jesuits were in large part brought by bishops or priests of high character, but the Jesuit writers airily dismiss them by giving the reader the impression that they were fabrications of wicked enemies of Christ. It would be fatal to admit that the Pope endorsed the indictment, so the apologists uniformly say, in one of their most brazen perversions of facts, that in the Bull “no blame is laid by the Pope on the rules of the Order, or the present condition of its members, or the orthodoxy of their teaching.” (That is the language of the Catholic Encyclopaedia). The Pope is represented as being reluctantly forced by circumstances to suspend the Society for the time. The truth is that the Pope enumerates at length all the charges against the Jesuits and fully endorses them. He recalls that thirteen previous Popes have condemned their practices and their doctrines after full inquiry, but he says the remedies had “neither efficacy nor strength to put an end to the trouble.” Therefore, “recognizing that the Society of Jesus can no longer produce the abundant fruits and the considerable advantages for which it was created,” he “suppresses and abolishes the Society for ever.” Catholic writers in grossly misrepresenting the Pope's action, take advantage of the fact that no English translation of the Bull is available, the last published being in The Jesuits by R. Demaus (1873). The essential parts of it are translated from Latin by the present writer in the book listed below. The Society was restored in the sanguinary reaction that followed the fall of Napoleon and the Jesuits returned to their pernicious intrigues. To-day they are a body of very comfortable mediocrities confining their love of intrigue to the capture of rich Catholics for their own parishes for which most priests cordially detest them and angling for aristocratic or semi-aristocratic converts. They have no distinction in learning or literature in spite of their wealth and leisure and they are superior to the other clergy only in their audacity in untruth and their solicitous ministration to the wealthy. See McCabe's Candid History of the Jesuits (1913). F. A. Ridley's The Jesuits (1938) is a sound, shorter, but broader study. A. Close's Jesuit Plots Against Great Britain (1935) is generally reliable. Of the works recommended in Robertson's Courses of Study, all of which are outdated, Nicolini's History of the Jesuits (1853) is unreliable, and Crétineau-Joly's Histoire religieuse, politique, et littéraire de la Compagnie de Jesus (6 vols., 1845-6), which all encyclopaedias recommend as the standard authority, is a monstrous piece of Jesuitry subsidized by the Jesuits themselves. The Jesuit Historian, Nicolini, stated in regard to the Jesuits: “Draw the character of the Jesuit as he seems in London and you will not recognize the portrait of the Jesuit in Rome. The Jesuit is a man of circumstances, despotic in Spain, constitutional in England, republican in Paraguay, bigot in Rome, idolater in India. He will assume and act out in his own person all those different features by which men are usually distinguished from each other. He will accompany the gay women of the world to the theatre and will share in the excess of the debauchery. With solemn countenance he will take his place by the side of the religious manner church or will revel in the tavern with a glutton or sot. He dresses in all garbs, speaks all languages, knows all customs, is present everywhere though nowhere recognized and all this it would seem, Oh Monstrous Blasphemy, “for the greater glory of God.” The Jesuits backed the Inquisition with all it’s elaborate and barbarous system of tortures and murders, putting to death millions of people. The Jesuits recon it among the glories of their Order that Loyola himself, supported by a special memorial to the Pope a petition to reorganize that cruel and abhorrent tribunal, the Inquisition. Under the shadow of that hellish monster the infernal flames of the most vile persecution were stoked while the Jesuits looked on with a sinister and diabolical smile across their faces.

History of the Jesuits. [1] E xcerpted from the massive 2 vol. History of Protestantism Dr. Wylie's massive History was published in 1878. The Jesuits did not self-destruct with the fall of the Papal States in 1870. As a matter of fact, that momentous event spurred them on to greater effort. The highest ranking Jesuit priest ever to escape that system and come to Christ was Dr. Alberto Rivera. He was a Bishop under the Extreme Oath of Induction. Normally, a person of such high rank who wants out knows too much, and always leaves feet first. God miraculously spared his life for 30 years. He finally succumbed to Jesuit poison in June, 1997. Dr. Rivera authenticates everything that Dr. Wylie says in his book and the half has not been told. Alberto Rivera as a young Spanish Jesuit priest during the Franco regime Dr. Rivera (the man who knew too much) after his conversion to Christ in 1967. Dr. Rivera became a martyr for Jesus in 1997. His brave widow is courageously carrying on his mission.

Ignatius Loyola. Rome’s New Army — Ignatius Loyola — His Birth — His Wars — He is Wounded — Betakes him to the Legends of the Saints — His Fanaticism Kindled — The Knight-Errant of Mary — The Cave at Manressa — His Mortifications — Comparison between Luther and Ignatius Loyola — An Awakening of the Conscience in both — Luther turns to the Bible, Loyola to Visions — His Revelations.

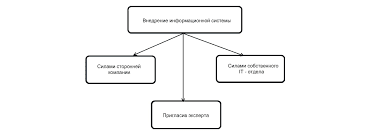

….. Don Inigo Lopez de Recalde, the Ignatius Loyola of history, was the founder of the Order of Jesus, or the Jesuits. His birth was nearly contemporaneous with that of Luther. He was the youngest son of one of the highest Spanish grandees, and was born in his father’s Castle of Loyola, in the province of Guipuzcoa, in 1491. His youth was passed at the splendid and luxurious comfort of Ferdinand the Catholic. Spain at that time was fighting to expel the Moors, whose presence on her soil she accounted at once an insult to her independence and an affront to her faith. She was ending the conflict in Spain, but continuing it in Africa. The naturally ardent soul of Ignatius was set on fire by the religious fervor around him. He grew weary of the gaieties and frivolities of the court; nor could even the dalliances and adventures of knight-errantry satisfy him. He thirsted to earn renown on the field of arms. Embarking in the war which at that time engaged the religious enthusiasm and military chivalry of his countrymen, he soon distinguished himself by his feats of daring. Ignatius was bidding fair to take a high place among warriors, and transmit to posterity a name encompassed with the halo of military glory — but with that halo only. At this stage of his career an incident befell him which cut short his exploits on the battlefield, and transferred his enthusiasm and chivalry to another sphere. It was the year 1521. Luther was uttering his famous “No!” before the emperor and his princes, and summoning, as with trumpet-peal, Christendom to arms. It is at this moment the young Ignatius, the intrepid soldier of Spain, and about to become the yet more intrepid soldier of Rome, appears before its. He is shut up in the town of Pamplona, which the French are besieging. The garrison are hard pressed: and after some whispered consultations they openly propose to surrender. Ignatius deems the very thought of such a thing dishonor; he denounces the proposed act of his comrades as cowardice, and re-entering the citadel with a few companions as courageous as himself, swears to defend it to the last drop of his blood. By-and-by famine leaves him no alternative save to die within the walls, or to cut his way sword in hand through the host of the besiegers. He goes forth and joins battle with the French. As he is fighting desperately he is struck by a musket-ball, wounded dangerously in both legs, and laid senseless on the field. Ignatius had ended the last campaign he was ever to fight with the sword: his valor he was yet to display on other fields, but he would mingle no more on those which resound with the clash of arms and the roar of artillery. The bravery of the fallen warrior had won the respect of the foe. Raising him from the ground, where he was fast bleeding to death, they carried him to the hospital of Pamplona, and tended him with care, till he was able to be conveyed in a litter to his father’s castle. Thrice had he to undergo the agony of having his wounds opened. Clenching his teeth and closing his fists he bade defiance to pain. Not a groan escaped him while under the torture of the surgeon’s knife. But the tardy passage of the weeks and months during which he waited the slow healing of his wounds, inflicted his ardent spirit a keener pain than had the probing-knife on his quivering limbs. Fettered to his couch he chafed at the inactivity to which he was doomed. Romances of chivalry and tales of war were brought him to beguile the hours. These exhausted, other books were produced, but of a somewhat different character. This time it was the legends of the saints that were brought the bed-rid knight. The tragedy of the early Christian martyrs passed before him as he read. Next came the monks and hermits of the Thebaic deserts and the Sinaitic mountains. With an imagination on fire he perused the story of the hunger and cold they had braved; of the self-conquests they had achieved; of the battles they had waged with evil spirits; of the glorious visions that had been vouchsafed them; and the brilliant rewards they had gained in the lasting reverence of earth and the felicities and dignities of heaven. He panted to rival these heroes, whose glory was of a kind so bright, and pure, that compared with it the renown of the battlefield was dim and sordid. His enthusiasm and ambition were as boundless as ever, but now they were directed into a new channel. Henceforward the current of his life was changed. He had lain down “a knight of the burning sword” — to use the words of his biographer, Vieyra — he rose up from it “a saint of the burning torch.” The change was a sudden and violent one, and drew after it vast consequences not to Ignatius only, and the men of his own age, but to millions of the human race in all countries of the world, and in all the ages that have elapsed since. He who lay down on his bed the fiery soldier of the emperor, rose from it; the yet more fiery soldier of the Pope. The weakness occasioned by loss of blood, the morbidity produced by long seclusion, the irritation of acute and protracted suffering, joined to a temperament highly excitable, and a mind that had fed on miracles and visions till its enthusiasm had grown into fanaticism, accounts in part for the transformation which Ignatius had undergone. Though the balance of his intellect was now sadly disturbed, his shrewdness, his tenacity, and his daring remained. Set free from the fetters of calm reason, these qualities had freer scope than ever. The wing of his earthly ambition was broken, but he could take his flight heavenward. If earth was forbidden him, the celestial domains stood open, and there worthier exploits and more brilliant rewards awaited his prowess. The heart of a soldier plucked out, and that of a monk given him, Ignatius vowed, before leaving his sick-chamber, to be the slave, the champion, the knight-errant of Mary. She was the lady of his soul, and after the manner of dutiful knights he immediately repaired to her shrine at Montserrat, hung up his arms before her image, and spent the night in watching them. But reflectin   Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|