|

|

WHERE’S THE SIN IN GIVING MONEYTO EDUCATE THE MOST UNFORTUNATE? By Charles Moore

Not many people who read this article send their children to city academies. And that, really, is the point. This innovation of the Blair Government, which built on the city technology colleges invented under Margaret Thatcher, is for people who do not read broadsheet newspapers; indeed, it is for people who often cannot read at all. It is unlikely, unfortunately, that such people will find a forum to explain their needs to the public. And even if they did, not all of them would be able to use it, because many of them are young children. It is therefore possible that the media will allow the fate of city academies to be subsumed into the great Labour sleaze argument. The link was made because one academy headmaster, lured by the delights of a good dinner with a young woman who was in fact an undercover reporter, started to talk big. Des Smith boasted of his government connections and allegedly indicated that people who gave money to help found city academies would receive peerages or knighthoods. Now our publicity-crazed police have actually arrested the poor fellow. It is indeed a sad day for British justice and for relations between the sexes if a middle-aged man cannot show off to a much younger woman in a restaurant – without attracting the interest of the constabulary. An alliance is forming between all those non-Labour voters who are longing for Tony Blair to fall and all those on the Left of Labour who want the same thing for different reasons. Personally, I have no desire to keep Tony Blair in office a moment longer, but I would still argue that this is a bad alliance, and the case of the city academies shows why. In his grim vision of what might be in A Christmas Carol Charles Dickens imagined two appalling children, one called Ignorance and the other called Want. He saw them as going together, but Ignorance as being worse "for on his brow, I see that written which is Doom". It is a special achievement of our times to have relieved want but to have preserved, perhaps even to have advanced, ignorance. In pockets of most British cities is abysmal ignorance - ignorance of anything that schools can teach, ignorance of codes of behaviour that make life tolerable, ignorance of how to raise children. It may be feeble and Lefty to say "Society's to blame" for all of this, but what is certain is that society has to try to do something about it. What is also certain is that the largest single social intervention in these areas - the "bog-standard" comprehensive school – does not work, and horrifying numbers of local authorities, which have these schools in their charge, do not seem to mind. Until schools do start to work, ignorance will persist. The point of city academies is to take the comprehensive ideal – the idea of "adding value" to everyone in an area regardless of his or her ability – and make it real. Unlike comprehensives, they are independent, though chiefly state-funded, and can run themselves. So far, there are 27 city academies, and by September there will be 50. Eventually, it is hoped, there will be 200. Some of them are entirely new enterprises; others are replacements for what the Government calls "failing schools". The academies enter the worst areas, the ones with the largest proportion of "FSMs". FSM stands for free school meal and it provides a rough guide to where the problems are likely to be the largest the national average for FSMs is 14 per cent. The average among the city academies is 39 per cent. In one place where an academy is taking over from a failing school, 40 out of the 180 11-year-olds have no discernible reading age. At another, a girl was recently gang-raped on the premises and another pupil was stabbed in the eye. In another, where governors had to consider the "exclusion" of 10 pupils, only two parents turned up to put their child's case to the governors. Controversy about the academies arises for two reasons. The first is that true believers in comprehensives resent any suggestion that any other form of school should be permitted, let alone supplant existing comps. This seems to me so stupid that I shall not bother to argue with it. The second reason is that city academies involve an unusual mixture of private and public money. The capital cost of setting one up is, on average, £27 million, and the contribution made by the sponsor is generally £2 million. For this modest proportion, critics argue, the sponsor gets a lot of advantage, too much influence and often, it is now alleged, an honor. It takes a perverse genius of propaganda to look at the matter in such a light what is happening is that people with private money are offering it to help educate children who lack all the advantages that they themselves either inherited or acquired. Surely that is exactly what should happen in a nation where, in David Cameron's phrase, there is such a thing as society and it is not the same as the state. In old, rich educational institutions such as Oxford and Cambridge colleges, there are annual services (followed by feasts) of the commemoration of benefactors. A great list of people, often dating back to the middle Ages, is read out. As the names roll on, you neither know nor care what the original motive of the donor was. Some may have been saintly people, actuated only by Christian charity. Others may have been trying to buy favor, influence, title, immortal fame. Most, probably, mixed their motives. It does not matter: the point is that they all gave, and that the cumulative effect of their gifts is good. Now that Britain is once again a rich society, after a century of wars and punitive taxes, it is the absolute duty of people with money to give much more too social causes, and of governments to do everything possible to encourage them. If honors help, I don't mind muck do you? Actually, the evil fat cats who are backing the academies turn out, in almost all cases, to be people of the deepest respectability. There are old education-related charities, such as Haberdashers and Mercers. There is the United Learning Trust, whose chief executive, Sir Ewan Harper, has spent his career in wickedly plutocratic occupations such as sitting on the Archbishop of Canterbury’s Commission on Rural Areas directing the restoration of Lambeth Palace chapel. There is Lord Harris of Peckham, the carpet king, who has stuck to this cause for nearly 20 years. What is true, and all to the good, is that the attitude of a business is different from that of a bureaucracy. A business exists only to get things done, whereas a bureaucracy sees its own existence as an end in itself. If you think of an organization such as Ark (Absolute Return for Kids), which is a charity set up by people in hedge funds, with a plan to open seven city academies in London alone, you see that what attracts it about the scheme is what businessmen call "leverage". The leverage ratio (I. e. the money you put in compared with the amount of money the whole enterprise attracts) is about 15:1. That is good leverage. A small investment can bring a big return, but the return comes in the form of children with discipline, personal attention andeducation, instead of millions of pounds. I'm still struggling to understand what is so wicked. The Daily Telegraph, Saturday, April 22, 2006

WHY MEDICINE MAKES US FEEL WORSE By Sheena Meredith

Yesterday's headlines warning of risks attached to continuing use of beta-blockers to treat high blood pressure will have alarmed a good proportion of the estimated two million patients affected, as well as the thousands of people taking these drugs for other conditions. The huge media interest is a measure of the importance we attach to drug safety; but it also highlights wider issues about our attitudes to risk and disease prevention. The reports were based on the latest conclusions of the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (Nice) that beta-blockers should no longer be routinely prescribed as initial treatment for high blood pressure. Yesterday, patients were advised not to panic and to wait until their next GP appointment. When switching to other drugs, beta-blocker doses should be reduced gradually, so patients should certainly not stop taking them without consulting their doctor. However, it is also usual in the face of such news for GPs to experience a flood of worried callers, understandably so in the face of headlines screaming "stroke risk" and claiming that the drugs increased the risk of heart attacks and diabetes as well. Nice reviewed its recommendations ahead of schedule in the light of results of a major study, the Anglo-Scandinavian Cardiac Outcomes Trial, dubbed "Ascot". This actually compared just one beta-blocker, atenolol, combined with a thiazide diuretic (both older drugs), with a newer drug combination - and some experts have queried how much the results can be generalised to other beta-blockers. Notably, neither the Nice guidelines nor the Ascot results state that beta-blockers increase the risk of stroke and heart attack, rather that they are less effective in preventing them than other drug combinations. Instead, patients should first be prescribed diuretics, ACE inhibitors or calcium channel blockers or some combination thereof. Beta-blockers are still recommended in some situations, such as younger or potentially pregnant patients. Although the Ascot study results were published in the Lancet last September, doctors were advised to await the Nice report before changing their prescribing practices. In fact, prescribing for hypertension has already moved away from beta-blockers – the two million taking them for high blood pressure represent only about a third of the total number of treated patients. Beta-blockers form only one plank of a variety of drugs recommended in previous Nice – guidelines, published only in 2004. Both Nice and the British Hypertension Society recommend treating blood pressure at levels that embrace an estimated 40 per cent of the adult population. High blood pressure is notoriously under-diagnosed and under – treated, but already results in about 900 million prescriptions a year that represent 15 per cent of the primary care drugs budget. The financial cost is worth it: treating high blood pressure reduces the risks of the awesome consequences that may follow, including heart attacks, strokes, kidney disease and sudden death. The latest Nice assessment included a cost-analysis: although switching from beta-blockers to other recommended drugs could cost the NHS £58-4 million per year, the estimated saving just from not having to treat all those extra heart attacks and strokes is £221-9 million. However, with such a high proportion of the population on treatment, we may need to consider additional consequences, including alarm as a result of being confronted over the morning papers with headlines about a drug one is taking. Furthermore, drugs for high blood pressure are only part of the overall picture. Nice recommendations earlier this year increased the number of adults deemed to need statin treatment to reduce high cholesterol levels to more than five million – 14 per cent of the adult population. If Britain were to adopt American thresholds for treatment, the proportion would be even higher. Notably, another branch of the Ascot study also recommended that people with high blood pressure and other risk factors should receive statins irrespective of their cholesterol levels. Some experts are beginning to worry that turning a risk factor -such as high blood pressure – into a disease also has unanticipated effects. As the British Medical Journal noted, preventive medicine makes us miserable – the higher a population's exposure to modern medicine, the lower do its people tend to self-rate their health and wellbeing. People in poor parts of India have much lower expectations of healthcare and do not live as long as Americans -but they feel a lot less ill. Two thirds of the British population is now on some form of long-term medication whose aim is to treat or prevent illness or to enhance wellbeing. Attempts to give us longer and healthier lives have, to an extent, succeeded in the medicalised West. However, as London GP Dr Iona Heath argued in the BMJ, those lives may be increasingly dominated by feelings of illness and fear, as yesterday's headlines exemplify. We are increasingly good at measuring and setting targets for blood pressure and cholesterol levels, as well as for what the healthcare industry deems lifestyle factors – diet, weight, alcohol and smoking. We are less good at balancing the positive effects of all this measuring, medicalising and nagging against all their possible harms. There are no targets for optimum levels of wellbeing or, come to that, of acceptable rates of worry, or guilt, or even of drug-related complications. Should our healthcare aims, as a society, just seek to prolong life, or should we also aim to enhance its quality – or at least not reduce it to the extent of turning a majority of the population into patients? Would our overall wellbeing be improved more by, say, reducing (or abolishing) the waiting list for hip replacements, or speeding up cataract operations, or improving treatment for children with depression? Yesterday's announcement about beta-blockers certainly does not warrant panic. It could usefully generate a little more debate about whether it is indeed healthy for such a high proportion of the population to be on medication, and to consider itself sick.

The Daily Telegraph Thursday, June 29, 2006

ORBITUARIES

MICHAEL HARTNACK By Alex Duval Smith

Michael Hartnack believed that journalism is a vocation that can serve as a force for good. Before ending his career as a columnist for South African newspapers, he played an active role in the generation of reporters who laid foundations for free expression that will outlive the despotism of President Robert Mugabe in Zimbabwe. Born in what is now Zambia, Hartnack came from a family of journalists – both his grandfather and greatgrandfather on his mother's side had been in the profession. "Hat Rack" or "Heart Attack", as colleagues called him, said journalism to him was "not so much a profession as an inherited genetic disorder". He spent his early years in Mongu, Barotseland, where his father was a civil servant in the Colonial Service. At the age of 10 he was taken to England and educated at Hastings Grammar School, East Sussex. He joined his first newspaper, the Cambridge Evening News, straight from school as a trainee. But the story was better in Rhodesia where Ian Smith had just unilaterally declared independence from Britain to set up his white minority rule government. In 1966, Hartnack joined the Rhodesia Herald – a newspaper best known for the blank spaces that signalled the passage of the government censor. In 1968, Hartnack moved to the Inter-African News Agency (Iana, later Ziana), where he stayed for 13 years and rose to chief parliamentary reporter. During his time at Iana, Hartnack was an active member of the Rhode-sian Guild of Journalists, and its president from 1976 to 1980. Against the background of the guerrilla war against white rule, Hartnack resisted the white regime's censorship, news management and its attempts to intimidate journalists. He fought unsuccessfully for black colleagues to be paid the same as whites. He saw the flaws in the 1979 Lancaster House agreement, which paved the way for majority rule but left Zimbabwe with a dated, colonial rulebook – including censorship – which invited abuses by the incoming government of Joshua Nkomo and Robert Mugabe. Disappointed by Britain's failure to set an example for openness, Hartnack said: " AH the British government would do then was pontificate, as in South Africa post-1910." The pontificators changed skin colour and, in 1981, when the Zimbabwean government took over Iana, Hartnack was made redundant. After a short spell in South Africa, he returned to Zimbabwe and became a foreign correspondent, filing columns forpapers including the Daily Despatch and the Natal Witness. He was the correspondent of the South African Business Day until he fell victim to a brutal black-empowerment scythe that cut through the paper in the mid-1990s. From then on, needing to put his three children through university, he filed for The Times, for the American Associated Press (AP) news agency, Sky News television and Deutsche Welle radio. Towards the end of a career that had done nothing to lower his blood pressure, Hartnack at least received peer recognition when Rhodes University - the prestigious home of southern African journalism – awarded him an honorary doctorate of literature in 2003. The Grahamstown professors who sponsored him said: The qualities which place him in a special class are those which he has displayed under the fire reserved by repressive regimes of every political hue for those who seek to challenge or expose the official view of events. According to AP's Harare bureau chief, Angus Shaw, Hartnack was never a cynic. "Mike and I used to argue about the nobility of the profession," he said: We had the conversation many times – when a colleague was killed in Somalia and again, last year, when someone outside Zimbabwe had suggested that Mugabe was one of the great men of Africa. I would wonder what the point of what we do was. I would have my doubts. Mike always believed that journalists can make a difference. The Daily Telegraph correspondent Peta Thornycroft said: I always found him the most generous of journalists. He had more local information than any other I met so if I wanted to know some obscure date for some obscure legislation and its history, he knew. And his information was so balanced. The last published column written by Hartnack before a stroke killed him on 2 August was about a black colleague, Andrew Kanyowa, whose funeral he had just attended. Epithetically, the piece paid tribute to Kanyowa whom Hartnack had got to know 40 years earlier on the Rkodeski Heratd "Through Andy," he wrote, "I became aware that it was not possible for any African to live in Rhodesia without being daily, hourly, reminded he belonged to a conquered people," Hartnack contrasted Rhodesia with present-day Zimbabwe and the new elite that holds its countryin a new kind of servile relationship. Teenage girls work for wealthy urban families under conditions close to slavery. New farm owners pay their labourers far less than the statutory minimum wage. This is not the sort of society for which black or white people like Andrew Kanyowa hoped and worked. Michael Hartnack, journalist: born Mongu, Barotseland 17 October 1945; married (two sons, one daughter); died Harare 2 August 2006.

The Independent Friday, 25 August, 2006 ADVERTISEMENT

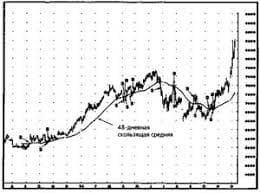

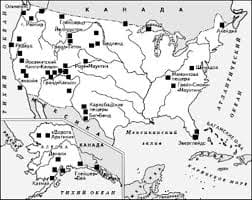

Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|