|

|

The subject-matter of lexicology and its main problemsСтр 1 из 10Следующая ⇒ The subject-matter of lexicology and its main problems Lexicology as a science has both theoretical and practical value. As a theoretical science modern English Lexicology investigates: -the problems of word structure and word formation in modern English, -the semantic structure of English words, -the main principles of classification of the vocabulary units into various grouping -the development of the vocabulary -etymology of English words -the laws that govern the development of English in present The theoretical value of Lexicology becomes obvious if we realize that it forms the study of one of the three main aspects of language: its vocabulary, grammar and sound system. Lexicology came into being to meet the demands of many different branches of linguistics, namely lexicography, literary criticism and especially of foreign language teaching. As for the practical value, it stimulates the systematic approach to the facts of vocabulary and organized comparison of the foreign and native languages. It helps the students to master the literary standards of word usage, to acquire the necessary skills of usage different kinds of vocabularies; it prepares students for further independent work on improving and enriching their vocabulary. Lexicology and Phonetics Phonemes have no meanings of their own but they serve to distinguish between meanings, e.g. dog- dig. Their function is building up morphemes. It is exactly on the level of morphemes that the form-meaning unity is introduced into language. Discrimination between the words may be based upon the stress, e.g. import to Import. Stress also helps us to distinguish compounds from homonymous word groups, e.g. blackbird- black bird. Lexicology and Stylistics It studies many problems treated in Lexicology but from different point of view. These are the problems of: -meaning -connotations -synonyms -functional differentiation of the vocabulary according to the sphere of communication Lexicology and Grammar The difference and interconnection between Grammar and Lexicology is 1 of the most important controversial problems in Linguistics, e.g. the verbs say, talk, think is possible only for animate human subjects, it is obvious that not all animate nouns are human. English vocabulary as a system — words 1. the biggest units of morphology and the smallest of syntax 2. they embody the main structural properties and functions of the language 3.can form the utterance in combination with other such units 4.may be used in isolation — parts of words (morphemes) 1.cannot be divided into smaller meaningful units 2.function in speech only as constituent parts of words 3.more abstract and more general that of words 4.less autonomous — word-groups 1.set expressions - ready-made units with a specialized meaning of the whole 2.orthographic words - sequence of letters bounded by spaces on a page The word is the basic unit of language system, the largest on the morphologic and the smallest on the syntactic plane of linguistic analysis. The word is a structural and semantic entity within the language system. Lexicology(general or special) Ways of enriching the voc: 1) voc extension 2) semantic extension voc extension a)productive word-formation -affixation-rewrite -conversion-colour-to colour -composition-heart-broken -back-derivation-to beg b)non-patterned ways of word-creation -lexicalization-arms-arm -adjectivization -shortening-st.for street c)borrowing semantic extension a)polysemy(a word has more than one meaning) b)homonymy(identical words in sound and spelling but different in meaning)

The classification of the English vocabulary On the morphological level words are divided into 4 groups according to their morphological structure, namely the number and type of morphemes which compose them: -root or morpheme words - dog, hand; - derivatives - helpful; -compound words - notebook; -compound derivatives -left-handed; Another type of traditional lexicological grouping is known as word-families. All the words are grouped: -according to the root-morpheme, e.g. clog, doggie, dog-days etc. -according to a common suffix or prefix, e.g. handsome, troublesome, lonesome etc. The next step is classifying words not in isolation but taking them within actual utterances.(Notional words and Form words) Notional words can stand alone and have meaning and form a complete utterance; they function as primary or secondary members. Form words =functional words-empty words or auxiliaries, prepositions, conjunctions-they express grammatical relationships between words. Subdivisions of parts of speech are called lexico-grammatical groups (LGGs) - a class of wors which have a common lexico-grammatical meaning, a common paradigm, the same substituting elements and possibly a characteristic set of suffixes rendering the lexico-grammatical meaning. Thematic groups The words are associated, because the things they name occur together and are closely connected in reality, e.g. kinship: brother, sisier, uncle, aunt, mother, father, cousin. The relationship existing between elements of various levels is logically that of inclusion. Semanticists call it hyponymy. And what is more it is a constitutive principle in the organization of the vocabulary of all languages. Idiographic groups Unite words of different pa its of speech but thematic-ally related; they are classed according to the system of logical notions, e.«. the notion of light; light, n; to shine, v; bright, adi Semantic fields (Trier) Closely connected sectors of the voc, characterized by a common concept, e.g. school V: to educate, to teach... Adj: academic, scholastic... N: college, university... Semantic and Idiographic groups-одинаковые, разница в терминологии

Etymological composition of the English Word- Stock Words of native origin and their characteristics. The English vocabulary has the composite nature. From the point of view its origin the English words may be divided 2 layers: The ancient Indo- European layer comprises different semantic groups: -words expressed family relations: father, mother, son, daughter, brother; -words naming the most important objects and phenomena of nature: sun, moon, star, wind, water, wood, hill, stone, tree; -names of animals and birds: bull, cat, crow, goose, wolf; -parts of human body: arm, ear, eye, foot, heart; -some of the most frequent verbs: bear, come, sit, stand; -the adjectives denoting concrete physical properties: hard, quick, slow, red, white. -most numerals. A much bigger part of the native vocabulary layer is formed by words of the Common Germanic stock: names of seasons -phenomena of nature: storm, ice -the most common actions: to burn, die + -nouns: ground, bridge, house, shop, room, coal, iron, lead, cloth, hat, hand, life, sea, ship, hope, etc; -many adverbs and pronouns; -verbs: bake, buy, drive, hear, keep, learn; -adjectives: broad, dead, deaf, deep. The English proper element – specifically English words having no cognates in other languages: bird, boy, girl, lady, lord, woman, daisy, always. Mechanism of borrowing According to the character borrowing may be divided into several groups: True loan words the words taken into the language in more or less the same phonetic form in which they existed in their own language. Such words may undergo the process of assimilation, and become associated with the native words, but sometimes they become undistinguishable from the native elements, e.g. to take -transcription the rendering of the sound form of a foreign word by the letters of the alphabet of another language, - transliteration the rendering of the letters of one alphabet by the equivalents in the other, e.g. kolhoz - transplantation the transferring of a word form from one language into another without changing its graphic form, e.g. tete-a-tete 2) translation loans/calques are a special kind of borrowing in the adoption of a word, not in the same phonetic shape, it has been functioning in its own language but after undergoing the process of translation, e.g. self-critisism 3) semantic loans the term used to denote the development of a new meaning due to the influence of a related word in another language Types of meaning Lexical meaning in morpheme can be analyzed into denotational (the component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible) and connotational (the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word; it can be found not only in root morphemes but in affixational morphemes as well) components, e.g. The morphemes, e.g. -ly, -like, -ish, have the denotational meaning of similarity in the words womanly, womanlike, womanish, the connotational component, however, differs and ranges from the positive evaluation in -ly (womanly) to the derogatory in -ish (womanish): женственный — женский — женоподобный, бабий. Functional – the part of speech meaning. The root-morphemes do not possess the part-of-speech meaning (cf. manly, manliness, to man); but derivational morphemes carry this meaning. In some morphemes, however, for instance -ment or -ous (as in movement or laborious), it is the part-of-speech meaning that prevails, the lexical meaning is but vaguely felt. In some cases the functional meaning predominates. The morpheme -ice in the word justice, e.g., seems to serve principally to transfer the part-of-speech meaning of the morpheme just — into another class and namely that of noun. It follows that some morphemes possess only the functional meaning, i.e. they are the carriers of part-of-speech meaning. Differential meaning is the semantic component that serves to distinguish one word from all others containing identical morphemes. In words consisting of two or more morphemes, one of the constituent morphemes always has differential meaning. In such words as, e. g., bookshelf, the morpheme -shelf serves to distinguish the word from other words containing the morpheme book-, e.g. from bookcase, book-counter and so on. Distributional meaning – the meaning of the order and arrangement of morphemes making up the word. It is found in all words containing more than one morpheme. The word singer, e.g., is composed of two morphemes sing- and -er both of which possess the denotational meaning and namely ‘to make musical sounds’ (sing-) and ‘the doer of the action’ (-er). There is one more element of meaning, however, that enables us to understand the word and that is the pattern of arrangement of the component morphemes. A different arrangement of the same morphemes, e.g. *ersing, would make the word meaningless. The combining form allo- from Greek allos ‘other’ is used in linguistic terminology to denote elements of a group whose members together constitute a structural unit of the language (allophones, allomorphs). Thus, for example, -ion/-sion/-tion/-ation in are the positional variants of the same suffix. To show this they are here taken together and separated by the sign /. They do not differ in meaning or function but show a slight difference in sound form depending on the final phoneme of the preceding stem. They are considered as variants of one and the same morpheme and called its allomorphs.So the allomorph is a position variant of a morpheme which may slightly differ in form or spelling IC method The method is based on the fact that a word characterised by morphological divisibility (analysable into morphemes) is involved in certain structural correlations. Breaking a word into its immediate constituents we observe in each cut the structural order of the constituents (which may differ from their actual sequence). Furthermore we shall obtain only two constituents at each cut, the ultimate constituents, however, can be arranged according to their sequence in the word: un-+gent-+-le+-man+'ly. CLASSIFICATION OF AFFIXES The analysis of such words can be done on two levels: 1)morphemic (we analyze morphemes which build words); 2)derivational (words are analyzed from the point of view of their structure – complex or not). Simple words contain only the primary stem (man, girl, take, go). Derived or compound words also contain derivational affixes. Prefixes mostly modify the lexical meaning of the word: Suffixes do change the meaning of the word, but also they can change the lexico-grammatical class of the word (the part of speech). It must be said that there are two types of prefixes: those that can be used as independent words (free morphemes) (like in the words to undercook – to go under); those that can’t function independently (bound morphemes) (mis - - to misunderstand). As a rule prefixes do not change the part of speech, but there are several of them which do so. That’s why they are called convertive (changing the form/ the part of speech). Prefixes can be classified according to their origin. Here they can be divided into native and borrowed. Prefixes can also be classified into productive (which take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development) and non-productive. Prefixes can belong to different styles. According to their meaning English prefixes are grouped the following way (the major groups): those of negative meaning (dis - - disloyal); those denoting words with the opposite meaning or with the meaning of repetition of some action (un- - undress); those denoting space, time and other relations (pre- - prewar). The main classification of suffixes is based on the parts of speech. There can be: noun suffixes (-dom – freedom); adjectival (adjective forming) suffixes (-ful – wonderful); verb-forming suffixes (-en – to shorten); adverb suffixes (-ly). From the point of view of meaning noun suffixes indicate a doer of an action; the relation of possession, belonging to some group; collectivity and other similar notions; diminutiveness; feminine gender. As for other peculiarities of English suffixes, there are those that change the part of speech and those that don’t do it (grey - greyish). The semantic type of the word can be changed with the help of some suffixes. For example, some words denoting objects become abstract (leader – leader ship). As well as prefixes, English suffixes can be stylistically coloured or neutral. Since any living language can develop, there are some changes in the meaning of its affixes. That’s why we have such phenomena as polysemy, homonymy and synonymy of affixes. It’s only natural that affixes have several meanings. Even the most famous ones. -er – 1) a doer of some action (a living being); 2) an object (boiler); 3) a person who is in some state (watcher); 4) distinguishes a feature of a man (chatter). 1) adverb-forming (quietly, readily); By productive affixes we mean those that take part in deriving new words in this particular period of language development. The best way to identify productive affixes is to look for them among neologisms (new words and occasional words). From the etymological point of view affixes are divided into the same two large groups as words: native and borrowed. For the affix to be called borrowed the total number of words with this affix must be considerable in the new language.

SEMI-AFFIXES Semi-affix – a free form in the E. vocabulary which has acquired valency similar to that of affixes.

I.e.: land, the pronunciation [lænd] occurs only in ethnic names Scotland, Finland and the like, but not in homeland or fatherland. As these elements seem to come somewhere in between the stems and affixes, the term semi-affix has been offered to designate them. A great combining capacity characterises the elements -like, -proof and -worthy, so that they may be also referred to semi-affixes, i.e.: godlike, gentlemanlike, ladylike, unladylike, manlike, childlike, unbusinesslike, suchlike, noteworthy, praiseworthy, seaworthy, trustworthy, and unseaworthy, untrustworthy, unpraiseworthy. -wise traditionally referred to adverb-forming suffixes: otherwise, likewise, clockwise, crosswise, etc. -way and -way(s) representing the Genitive: anyway(s), otherways, always, likeways, side-way(s), crossways, etc. -proof: damp-proof, fire-proof, bomb-proof, waterproof, shockproof, kissproof (about a lipstick), foolproof (about rules, mechanisms, etc., so simple as to be safe even when applied by fools). Semi-affixes may be also used in preposition like prefixes. Thus, anything that is smaller or shorter than others of its kind may be preceded by mini-: mini-budget, mini-bus, mini-car, mini-crisis, mini-planet, mini-skirt, etc. Other productive semi-affixes used in pre-position are midi-, maxi-, self- and others: midi-coat, maxi-coat, self-starter, self-help. The factors conducing to transition of free forms into semi-affixes are high semantic productivity, adaptability, combinatorial capacity (high valency), and brevity. HYBRIDS Words that are made up of elements derived from two or more different languages are called hybrids. Here distinction should be made between two basic groups: Cases when a foreign stem is combined with a native affix, as in colourless, uncertain. After complete adoption the foreign stem is subject to the same treatment as native stems and new words are derived from it at a very early stage. For instance, such suffixes as -ful, -less, -ness were used with French words as early as 1300; Cases when native stems are combined with foreign affixes, such as drinkable, joyous, shepherdess. Here the assimilation of a structural pattern is involved, therefore some time must pass before a foreign affix comes to be recognised by speakers as a derivational morpheme that can be tacked on to native words. Therefore such formations are found much later than those of the first type and are less numerous. The early assimilation of -able is an exception. Some foreign affixes, as -ance, -al, -ity, have never become productive with native stems. Types of word meaning It is more or less universally recognised that word-meaning is not homogeneous but is made up of various components the combination and the interrelation of which determine to a great extent the inner facet of the word. These components are usually described as types of meaning. The two main types of meaning that are readily observed are the grammatical and the lexical meanings to be found in words and word-forms. Grammatical Meaning We notice, e.g., that word-forms, such as girls, winters, joys, tables, etc. though denoting widely different objects of reality have something in common. This common element is the grammatical meaning of plurality which can be found in all of them. Thus grammatical meaning may be defined,as the component of meaning recurrent in identical sets of individual forms of different words, as, e.g., the tense meaning in the word-forms of verbs (asked, thought, walked, etc.) or the case meaning in the word-forms of various nouns (girl’s, boy’s, night’s, etc.). In a broad sense it may be argued that linguists who make a distinction between lexical and grammatical meaning are, in fact, making a distinction between the functional (linguistic) meaning which operates at various levels as the interrelation of various linguistic units and referential (conceptual) meaning as the interrelation of linguistic units and referents (or concepts). In modern linguistic science it is commonly held that some elements of grammatical meaning can be identified by the position of the linguistic unit in relation to other linguistic units, i.e. by its distribution. Word-forms speaks, reads, writes have one and the same grammatical meaning as they can all be found in identical distribution, e.g. only after the pronouns he, she, it and before adverbs like well, badly, to-day, etc. It follows that a certain component of the meaning of a word is described when you identify it as a part of speech, since different parts of speech are distributionally different (cf. my work and I work). Lexical Meaning Comparing word-forms of one and the same word we observe that besides grammatical meaning, there is another component of meaning to be found in them. Unlike the grammatical meaning this component is identical in all the forms of the word. Thus, e.g. the word-forms go, goes, went, going, gone possess different grammatical meanings of tense, person and so on, but in each of these forms we find one and the same semantic component denoting the process of movement. This is the lexical meaning of the word which may be described as the component of meaning proper to the word as a linguistic unit, i.e. recurrent in all the forms of this word. The difference between the lexical and the grammatical components of meaning is not to be sought in the difference of the concepts underlying the two types of meaning, but rather in the way they are conveyed. The concept of plurality, e.g., may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the world plurality; it may also be expressed in the forms of various words irrespective of their lexical meaning, e.g. boys, girls, joys, etc. The concept of relation may be expressed by the lexical meaning of the word relation and also by any of the prepositions, e.g. in, on, behind, etc. (cf. the book is in/on, behind the table). “ It follows that by lexical meaning we designate the meaning proper to the given linguistic unit in all its forms and distributions, while by grammatical meaning we designate the meaning proper to sets of word-forms common to all words of a certain class. Both the lexical and the grammatical meaning make up the word-meaning as neither can exist without the other. That can be also observed in the semantic analysis of correlated words in different languages. E.g. the Russian word сведения is not semantically identical with the English equivalent information because unlike the Russian сведения the English word does not possess the grammatical meaning of plurality which is part of the semantic structure of the Russian word. Parf-of-Speech Meaning It is usual to classify lexical items into major word-classes (nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs) and minor word-classes (articles, prepositions, conjunctions, etc.). All members of a major word-class share a distinguishing semantic component which may be viewed as the lexical component of part-of-speech meaning. For example, the meaning of ‘thingness’ or substantiality may be found in all the nouns e.g. table, love, sugar, though they possess different grammatical meanings of number, case, etc. The grammatical aspect of the part-of-speech meanings is conveyed as a rule by a set of forms. If we describe the word as a noun we mean to say that it is bound to possess a set of forms expressing the grammatical meaning of number (cf. table — tables), case (cf. boy, boy’s) and so on. A verb is understood to possess sets of forms expressing, e.g., tense meaning (worked — works), mood meaning (work! — (I) work), etc. The part-of-speech meaning of the words that possess only one form, e.g. prepositions, some adverbs, etc., is observed only in their distribution (cf. to come in (here, there) and in (on, under) the table). One of the levels at which grammatical meaning operates is that of minor word classes like articles, pronouns, etc. Members of these word classes are generally listed in dictionaries just as other vocabulary items, that belong to major word-classes of lexical items proper (e.g. nouns, verbs, etc.). One criterion for distinguishing these grammatical items from lexical items is in terms of closed and open sets. Grammatical items form closed sets of units usually of small membership (e.g. the set of modern English pronouns, articles, etc.). New items are practically never added. Lexical items proper belong to open sets which have indeterminately large membership; new lexical items which are constantly coined to fulfil the needs of the speech community are added to these open sets. The interrelation of the lexical and the grammatical meaning and the role played by each varies in different word-classes and even in different groups of words within one and the same class. In some parts of speech the prevailing component is the grammatical type of meaning. The lexical meaning of prepositions for example is, as a rule, relatively vague (independent of smb, one of the students, the roof of the house). The lexical meaning of some prepositions, however, may be comparatively distinct (cf. in/on, under the table). In verbs the lexical meaning usually comes to the fore although in some of them, the verb to be, e.g., the grammatical meaning of a linking element prevails (cf. he works as a teacher and he is a teacher). Denotational and Connotational Meaning Proceeding with the semantic analysis we observe that lexical meaning is not homogenous either and may be analysed as including denotational and connotational components. One of the functions of words is to denote things. The same meaning for all speakers of the language is the denotational meaning, i.e. that component of the lexical meaning which makes communication possible. The second component of the lexical meaning is the connotational component, i.e. the emotive charge and the stylistic value of the word. Emotive Charge and Stylistic Reference As a rule stylistically coloured words, i.e. words belonging to all stylistic layers except the neutral style are observed to possess a considerable emotive charge. That can be proved by comparing stylistically labelled words with their neutral synonyms. The colloquial words daddy, mammy are more emotional than the neutral father, mother; the slang words mum, bob are undoubtedly more expressive than their neutral counterparts silent, shilling, the poetic yon and steed carry a noticeably heavier emotive charge than their neutral synonyms there and horse. Words of neutral style, however, may also differ in the degree of emotive charge. We see, e.g., that the words large, big, tremendous, though equally neutral as to their stylistic reference are not identical as far as their emotive charge is concerned. Types of context Polysemy is closely connected with the notion of the context (the minimum stretch of speech which is sufficient to understand the meaning of a word). The main types of context are lexical and grammatical. Lexical context (the lexical environment of a word): heavy, adj: in isolation: of great weight, weighty combined with industry, arms, artillery: the larger kind of… Grammatical context. The grammatical structure of the context that serves to determine various individual meanings of a polysemantic word. make, v: the meaning of force, “to induce” to make + pronoun + verb (to make smb laugh) the meaning “to become” to make + adj + noun (to make (стать) a good wife) Extra-linguistic context (context of situation). The meaning of the word is determined not only by linguistic factor, but by the actual speech situation in which the word is used. ring - a circlet of precious metal or a call on the telephone glasses – spectacles or drinking vessels

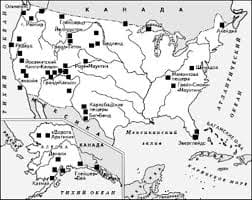

Types of semantic change Changes in the denotational meaning may result in the restriction of the types or range of referents denoted by the word. This may be illustrated by the semantic development of the word hound (OE. hund) which used to denote ‘a dog of any breed’ but now denotes only ‘a dog used in the chase’. This is generally described as “restriction of meaning” and if the word with the new meaning comes to be used in the specialised vocabulary of some limited group within the speech community it is usual to speak of specialisation of meaning. For example, we can observe restriction and specialisation of meaning in the case of the verb to glide (OE. glidan) which had the meaning ‘to move gently and smoothly’ and has now acquired a restricted and specialised meaning ‘to fly with no engine’ (cf. a glider). Changes in the denotational meaning may also result in the application of the word to a wider variety of referents. This is commonly described as extension of meaning and may be illustrated by the word target which originally meant ‘a small round shield’ (a diminutive of targe, сf. ON. targa) but now means ‘anything that is fired at’ and also figuratively ‘any result aimed at’. If the word with the extended meaning passes from the specialised vocabulary into common use, we describe the result of the semantic change as the generalisation of meaning. The word camp, e.g., which originally was used only as a military term and meant ‘the place where troops are lodged in tents’ (cf. L. campus — ‘exercising ground for the army) extended and generalised its meaning and now denotes ‘temporary quarters’ (of travellers, nomads, etc.). As can be seen from the examples discussed above it is mainly the denotational component of the lexical meaning that is affected while the connotational component remains unaltered. There are other cases, however, when the changes in the connotational meaning come to the fore. These changes, as a rule accompanied by a change in the denotational’ component, may be subdivided into two main groups: a) pejorative development or the acquisition by the word of some derogatory emotive charge, and b) ameliorative development or the improvement of the connotational component of meaning. The semantic change in the word boor may serve to illustrate the first group. This word was originally used to denote ‘a villager, a peasant’ (cf. OE. zebur ‘ dweller’) and then acquired a derogatory, contemptuous connotational meaning and came to denote ‘a clumsy or ill-bred fellow’. The ameliorative development of the connotational meaning may be observed in the change of the semantic structure of the word minister which in one of its meanings originally denoted ‘a servant, an attendant’, but now — ‘a civil servant of higher rank, a person administering a department of state or accredited by one state to another’. It is of interest to note that in derivational clusters a change in the connotational meaning of one member doe’s not necessarily affect a the others. This peculiarity can be observed in the words accident аn accidental. The lexical meaning of the noun accident has undergone pejorative development and denotes not only ’something that happens by chance’, but usually’something unfortunate’. The derived adjective accidental does not possess in its semantic structure this negative connotational meaning (cf. also fortune: bad fortune, good fortune and fortunate). The subject-matter of lexicology and its main problems Lexicology as a science has both theoretical and practical value. As a theoretical science modern English Lexicology investigates: -the problems of word structure and word formation in modern English, -the semantic structure of English words, -the main principles of classification of the vocabulary units into various grouping -the development of the vocabulary -etymology of English words -the laws that govern the development of English in present The theoretical value of Lexicology becomes obvious if we realize that it forms the study of one of the three main aspects of language: its vocabulary, grammar and sound system. Lexicology came into being to meet the demands of many different branches of linguistics, namely lexicography, literary criticism and especially of foreign language teaching. As for the practical value, it stimulates the systematic approach to the facts of vocabulary and organized comparison of the foreign and native languages. It helps the students to master the literary standards of word usage, to acquire the necessary skills of usage different kinds of vocabularies; it prepares students for further independent work on improving and enriching their vocabulary. Lexicology and Phonetics Phonemes have no meanings of their own but they serve to distinguish between meanings, e.g. dog- dig. Their function is building up morphemes. It is exactly on the level of morphemes that the form-meaning unity is introduced into language. Discrimination between the words may be based upon the stress, e.g. import to Import. Stress also helps us to distinguish compounds from homonymous word groups, e.g. blackbird- black bird. Lexicology and Stylistics It studies many problems treated in Lexicology but from different point of view. These are the problems of: -meaning -connotations -synonyms -functional differentiation of the vocabulary according to the sphere of communication Lexicology and Grammar The difference and interconnection between Grammar and Lexicology is 1 of the most important controversial problems in Linguistics, e.g. the verbs say, talk, think is possible only for animate human subjects, it is obvious that not all animate nouns are human.   Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|