|

|

By John F. Burns and Kirk SempleBAGHDAD: When President George W. Bush meets in Jordan on Wednesday with Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki of Iraq, it will be a moment of bitter paradox: at a time of heightened urgency in the Bush administration’s quest for solutions, American military and political leverage in Iraq has fallen sharply. Dismal trends in the war – measured in a rising number of civilian deaths, insurgent attacks, sectarian onslaughts and American troop casualties – have merged with growing American opposition at home to lend a sense of crisis to the talks in Amman. But American fortunes here are ever more dependent on feuding Iraqis who seem, at times, almost heedless to American appeals, American and Iraqi officials in Baghdad say. They say they see few policy options that can turn the situation around, other than for Iraqi leaders to come to a realization that time is running out. It is not clear that the United States can gain new traction in Iraq with some of the proposals outlined in a classified White House memorandum, which was compiled after the national security adviser, Stephen J. Hadley, visited Baghdad last month. Many of the proposals appear to be based on an assumption that the White House memo itself calls into question: that Prime Minister Maliki can be persuaded to break with 30 years of commitment to Shiite religious identity and set a new course, or abandon the ruling Shiite religious alliance to lead a radically different kind of government, a moderate coalition of Shiite, Sunni and Kurdish politicians. The memo’s assessment of Maliki tracks closely with what his American and Iraqi critics in Baghdad say: that six months after taking office, he has still not shown that he is willing or capable of rising above Shiite sectarianism. These critics say, in effect, that the 56-year-old Iraqi leader has failed, so far, to meet the test set by Bush when the two men met for the first time in Baghdad in June. At that meeting, the American leader told Maliki he had come to ''look you in the eye'' and determine if America had a reliable partner here. Against these judgments, some key passages in the Hadley memo seem at odds with the reality on the ground, as if the steady worsening of America’s prospects here has driven the White House to reach for solutions that defy the gloomy conclusions of America’s diplomats and field commanders, not to mention some of Maliki’s closest political associates. Even some powerful figures in the Shiite alliance have spoken recently of Maliki less as a possible leader of a parliamentary coup against the political movement that nurtured him than as an ineffective and ultimately dispensable figure, much like the man he succeeded in the prime minister’s office, Ibrahim al-Jaafari. Shiites in Iraq are riven by factional rivalries, and there may be opportunities for the Americans to exploit those divisions to create parliamentary realignments. Indeed, some Iraqi leaders have started exploring new alliances to break the political logjam, possibly involving a parliamentary coup against Maliki. But if Grand Ayatollah Ali al- Sistani, Iraq’s most powerful Shiite cleric, has been clear about anything, it has been that the Shiites must subordinate their differences to the cause of consolidating Shiite power. So it is hard to imagine Maliki approaching Ayatollah Sistani to win approval ''for actions that could split the Shia politically,'' as the Hadley memo suggests. Shiite leaders, who are tiring of Maliki, appear to be thinking of replacing him with another Shiite religious leader, and not of sundering the alliance and surrendering the power the Shiites have awaited for centuries. But if recent interviews in Baghdad with senior American and Iraqi officials are a guide, a bigger problem for the Bush administration in effecting change here may be that the United States, in toppling Saddam Hussein and sponsoring elections that brought the Shiites to power, began a process that left Washington with ever-diminishing influence. One reason for the declining American influence lies in policies that, for various reasons, alienated the political class, most of them former exiles like Maliki who rode back to Baghdad on the strength of American military power. Many Shiite leaders resent the Americans for compelling them to share power in the new government with the minority Sunni Arabs – a policy, the Shiites say, that guaranteed paralysis for the government. Sunni leaders still resent the American invasion, and the imposition of an electoral process that ended centuries of Sunni dominance. Just as much, they fume over the pervasive influence of neighboring Iran, which backs the Shiite parties. And secular politicians, marginalized by the Shiite and Sunni Islamist politicians who dominate the government, say they, too, have lost faith in the Americans, for failing to protect Iraq’s secular traditions. "Politically, their position is weaker in all aspects," Mahmoud Othman, a Kurdish leader, said of the Americans. "They just got weaker and weaker, and many more people who were supporting them are supporting them less." Meanwhile, the faltering of the latest effort to secure Baghdad has exposed the limitations of American ability to change the military equation. The White House memo raises the possibility of using additional American troops to fill what it calls "the four brigade gap" in troops committed to the Baghdad operation in August – a gap caused by Iraq’s new army committing only two of the six brigades it promised. That shortfall left Americans providing about two-thirds of the 25,000 troops, halting by mid-October the sweeps to clear districts of insurgents and death squads. But American commanders interviewed said that committing additional American troops could send a signal to Shiites, Sunni Arabs and Kurds that they could continue to quarrel over their share of political and economic power behind an American military shield. In recent days, Maliki has seemed to heed these American warnings, telling fellow Iraqi leaders on Sunday, three days after bombings that killed more than 200 Shiites in Sadr City, that they have to accept the blame for the surging violence. ''The crisis is political,'' Maliki said, ''and the ones who can stop the cycle of aggravation and bloodletting of innocent people are the politicians.'' Meanwhile, the political process has almost completely ground to a halt. Maliki’s ''national reconciliation plan,'' intended to reduce violence through dialogue and an amnesty program for militia fighters and insurgents, has stalled. Political leaders have also made little progress on promises to review the new Constitution, a document resented by Sunnis, and a plan to draft a new law that will set terms for the future divisions of oil revenues that account for 90 percent of Iraq’s economy. Saleh Mutlak, a Sunni legislator, was blunt in his assessment of the government: ''Do you not recognize that it’s going backwards? '' Sectarian rifts between the nation’s political leaders have deepened. During a session of Parliament last week, prominent Sunni and Shiite legislators bitterly accused each other of sectarianism and promoting violence. President Jalal Talabani, a Kurd, has warned fellow leaders about the possible collapse of the state. And even the Shiite leaders who control the government have taken to conspiring among themselves, with open jockeying for the succession if Maliki should fall. At the crux of the most difficult decisions facing Maliki stands the Shiite cleric Moktada al-Sadr, whose control of one of the largest blocs in Parliament, several ministries and a large and restless militia, makes him arguably the most powerful politician in Iraq. Maliki is indebted to Sadr for providing the votes within the ruling Shiite alliance that made him prime minister. But Sadr’s volatile militia, the Mahdi Army, is blamed for many of the Shiite revenge attacks against Sunnis. The White House memo suggests that Shiites might be willing to drop their support of the militia if the Americans continue their military pressure against Sunni insurgents. But Shiites see the militia as their last defense against decimation by Sunni insurgents. For the Iraqi leader, the challenge presented by Sadr and the Mahdi Army amounts to a zero-sum game. If Maliki moves too fast against the militia, he risks losing Sadr’s support and splintering the Shiite bloc. If he moves too slowly, he will alienate the Sunni Arabs whose cooperation is crucial to any hope of reining in the insurgency. Meanwhile, Maliki is in a vexed relationship with the United States. The Iraqi government needs the United States for the protection its 150,000 troops afford. At the same time, he has felt compelled to push back publicly against American pressures, partly to gain credibility among those in his power base who oppose the American presence, particularly the staunchly anti-American Sadr. Among other things, he has demanded effective control of Iraq’s new 140,000-man army, which remains under overall American command. According to several Iraqi politicians, Bush may consent in Jordan to arrangements that give Maliki at least greater nominal authority over the Iraqi forces, something American commanders – and the White House memo – agree would be important to Maliki’s credibility. But the Americans will be careful about the practical implications, because of concerns that the Iraqi police and army, overwhelmingly Shiite, could be used as a sectarian militia. Iraqis are growing impatient. ''The government should say they are going to take things into their own hands,'' said Adel Abdul Mahdi, the Shiite vice president and one of Maliki’s rivals for prime minister. ''We don’t have enough time,'' he continued. ''Iraqis have to deliver. We have to show the world that there is a state.''

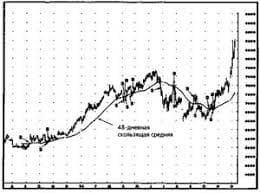

The New York Times, November 29, 2006 EDITORIALS ________________________________________________________ Editorials. Newspapers and magazines offer editorial opinions on subjects of current interest to their readers. The editors of the publication make a claim (a statement of truth, of value or of policy) about a newsworthy subject in order to try to convince their readers to agree with their claim. For instance, an editorial might urge readers to vote for a particular candidate or to support a particular charity. Readers are then invited to express their own opinions in response to editorials by writing letters to the publication. A reader's letter might be selected for publication on the editorial page or in the editorial column. If so, that letter might well be edited for conciseness. Thus, clarity of expression is doubly important.   ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|