|

|

THE DHARMA-PURANA — APPENDIX TO THE SHRISHTI-KHANDA .Although the Dharma-p. stands as an appendix to the Shrishti-khanda, still it deserves special attention for it plays an important part in the constitution of the Padma-p. as it stands today. That this Dharma-p 29 did not, in its origin, form an integral part of the Padma-p. proper but was an independent work, is shown definitely by the facts that all the Bengal mss. of the Shrishti-khanda (written in Bengali script) and one Devanagari ms. preserved in the 1,0., London 30 lack this portion and that the Brhaddharma-p. includes the name of the Dharma-p. in its list of eighteen Upapuranas 31, In course of time, however, this work came to be recognised as a part of the Shrishti-khanda, and it appears from the exclusion of this part from the Bengal mss of the Shrishti-khanda that this addition and recognition were not made in Bengal. Here we shall examine the Dharma p which has so long been regarded as a constituent part of the Shrishti khanda. That the Dharma-p was written m Kamarupa a little after the first Muhammadan invasion, can be proved by various evidences It contains a peculiar story of Garuda which runs as follows Immediately after his birth from Vmata by Kashyapa, Garuda felt very hungry and begged food from his mother, who, from a feeling of helplessness, referred him to his father Kashyapa practising penance on the northern bank of the river Lauhitya (modem Brahmaputra) 32 Accordingly, Garuda met his father there and informed him of his hunger The latter advised him to eat up the Nishadas living on the banks of the Lauhitya but not the brahmins residing with them 53 Now, Garuda acted according to his father’s advice but through mistake devoured up a brahmin also, as he was unable to distinguish him from others This brahmin stuck in his throat in such a way that he was able neither to devour him up nor to vomit him out Feeling extremely helpless, he reported the matter to his father, who, at the request of this brahmin, advised Garuda to vomit out all the Mlecchas together with the brahmin on all sides outside the country Consequently, Garuda gave out different Mleccha tribes in different directions Thus, in the east there were the hairless and beardless Yavanas as well as those who had scanty beard, m the south east there were the sinful Nagnakas (Nagas?), in the south there were the fierce, wicked and speechless people who took delight in killing animals and were beef eaters, in the south west there were the Kuvadas (people having a bad speech?) who were sinners and were always bent on falling cows and brahmins, in the west as well as in the east there were the fearful Kharparas; m the north-west there were the Turuskas, who had their faces co\ered with beard, were habituated beefeaters, rode on horse-back, and knew no retreat from battle, in the north there were the mountains and the Mlecchas living in them, eating everything without discrimination, and practising indiscipline, and capture and slaughter of human beings, and m the north-cast there are the Nirayas (hellish people’ >) living on trees 31 The mention of the Turuskas being driven out to the north-west ofKamarupa, cvidentl) refen to the Muhammadans who, after entering Kamarupa must have received a sc\erc set back with i crushing defeat and been driven away from the heart of the country to the north-w estem part of it Thus, it can safely be held that this Dharma^p was written in Kamarupa after the Muhammadan invasion referred to in the above story We know from inscnptionai, literary and other evidences that on his way to Tibet some time between 1203-1205 A D Md Bakhtyar Khilji, King of Bengal, entered Kamarfipa with an army of horse-men and received a severe blow from the reigning king of the territory 35 It is admitted that Bakhtyar Khilji was murdered in August 1206 AD M If about fifty years be taken to intervene between Bakhtyar Khilji’s expulsion from Klmarupa and The composition of the Dharma-p, then this work is to be dated not earlier tlnn the second half of the 13 th century A D. The upper limit of the date of composition of the Dharma p can be supported by other internal and external evidences, which are as follows The names of ribs and week day’s have been given more than once 3 ", the Tulasi plant has been named on several occasions 34, and the influence of the Agamas and Tamras is very prominent!) discernible in several places 33 There arc references to the Mlccchas 40 which seem to betray the knowledge of the author of the Dharma-p. of the evils of the rule of the Mleccha dynasty in Kamarupa. The comparatively late date of this part of the Shrishti-khanda is further evidenced by the fact that none of the numerous Smriti-writers is found to quote even a single line from this portion either under the name of the Dharma-p. or that of the Shrishti-khanda or Padma-p, although they have quoted frequently from the other part. The two vss. 41, quoted as from Padma-p, in Hemadn’s Caturvarga cintamani I p. 71 and found in chap. 47 of this part, need not be taken to assign this part to an earlier date. Traces of late origin contained in this part itself as well as the remarkable silence of all the Smriti-writers about its contents show definitely that these two vss. were taken by Hemadri from some earlier chap, of the Padma-p. which has been modified or lost. As to the lower limit of the date of the Dharma-p., we have already said that its name has been included in the list of eighteen Upapuranas given in the Brhaddharma-p (1. 25.23-26) which must have been composed not later than the end of the 14th century A D. 42 So, the Dharma-p. could not have been written later than 1325 A D. Thus, the date of composition of this work falls between 1250 and 1325 A D. In order to explain the rise and title of the Dharma-p. a picture of the religious condition of Kamarupa may be drawn from the materials contained in this book itself The socioreligious culture of the country had moved far away from the VarnaSramadharma advocated by the Smriti-writers. There were the Kiratas and the Kapalika Shaivas, who are referred to in the Kaltka-p. and other works as MIecchas, Sulapani, in his Durgotsava-viveka, ascribes to the Skanda-p. a vs. which refers to the worship by Kiratas which was bereft of sacrifices, mantras and their muttering but was furnished with the offering of wine, meat etc. This type of worship was known as Tamasi 43. The Bhavishya-p. also mentions that the Kapahkas took wine and meat profusely 44. Other references of this nature can be had from the Devi-p. and other works also In the Dharma-p there are similar accounts of the MIecchas. According to this work 45 the MIecchas were no better than slaves of their passions. They ate everything, beef, flesh of other animals, wine, onion etc. in particular. They roamed about with dogs in chains with them, took the remnants of food left by others, misappropriated the things deposited with them, killed infants, women, brahmins and cows, and carried away by force the w r omen-folk of others for their personal pleasure!They loved the company of bad people; their servants also became immoral; and their women sometimes became adulterous. In fact, they were impure in body and mind and did not care for purity, penance or knowledge. They did not believe in the Hindu customs and worship of gods, Pitrs, spiritual preceptors and parents or in the efficacy of gifts, Tarpana and Sraddha They were immoral to such an extent that they would desire even their own mothers and sisters for their sensual gratification. They were very cruel and prone to anger, and even towards their own children they did not entertain any feeling of affection The whole structure of the society collapsed under their influence. People in general learnt their dialect (described as pariacikl bhasfi) in order to have service under them, disbelieved the Puranas and the Agama Sarphitas and disrespected the elderly persons They deviated from the right path of Varndiramadharma, were jealous of one another, and became fraudulent The housewives were reluctant to take care of or attend upon their husbands, and other in laws Even the brahmins also had a great fall from the right path of the Vedic Dharma under the influence of these people They became devoid of purity, self control, mantras and sacraments They had no regard for the ancient scriptures, Sraddhas and other Pitrkarmans any more People in general gave up their own hereditary profession and began to adopt the art of craftsmanship, husbandry, agriculture and merchandise according to their own choice 45 During this time, the term Mleccha gained so much popularity that the kings of the Salastambha dynasty were not at all ashamed of giving themselves out as MIccchas 47 The use of this term by Harjaravarman, a descendant of Salastambha, with respect to his ow n ancestors sho%vs that it was popular in Kamarupa and did not mean as much disrespect or dishonour as it is generally presumed If the term would indicate humiliation, Harjaravarman, a descendant of Salastambha, would not have mentioned it in his own inscription This shows that the Mlecchas had spread so much influence throughout the country, that this term was not considered to bring dishonour and humiliation to anybody. The dismal picture of society, given above, is ascribed by the Dharma-p to the wide spread of KSpahka Shaivism, which did not come to Kamarupa all on a sudden There is no doubt about the fact that from early days Kamarupa was a stronghold of Shaivism It will not perhaps be out of place to refer to a story of the Kahka-p in this respect According to this story, all the rivers and mountains of this Mahapitha Kamarupa were sacred and the people dying there became the dwellers of the region of Shiva Yama’s messengers were thus being thrown out of employment, and his abode was experiencing a continuous fall in the number of sinners day by day. This troubled Brahma, Vishnu and others, and all of them went to Mahadeva to report to him all these matters. They requested Mahadeva to see that Yama was not superseded and he might rule over Kamarupa also without experiencing any decline in his power. Mahadeva agreed, and ordered his own Ganas and Devi Ugratara to expel all people from the sacred Pitha. Accordingly the latter began their work, and even the twice-born people Mere not spared. When Ugratara came to catch hold of Vasistha, the latter cursed her and her companions in the following way: “O perverse one, I am a sage, as }ou have caught even me with the intention of expelling, }ou, along with the Matrs, will be worshipped henceforth in a perverse w ay (or, according to the method of the Left-hand Shaktas). As >our wicked Ganas are wandering like Mlecchas, they will become Mlccchas in this Kamarupa.... Let Samkara, by besmearing his body with ashes and wearing bones, be the lover of the Mlecchas 481. There is another story in theKahka-p. which proves the antiquity of Shiva-worship in Kamarupa by referring to the fact that from very early times, Kamarupa was reserved for Shiva 49. All the available inscriptions belonging to the kings of Kamarupa, except one, evince obeisance to Shiva (called Mahdvara) 50 and thus clearly show that these kings were strong followers of Shaivism. That Bhaskaravarman was a devoted worshipper of Shiva has been clearly referred to in Banabha^a’s I/arjacanicP 1 The tracing of the lineage of kings of Kamarupa to Vishnu through Naraka, does not mean that the worship of Vishnu was prevalent m Assam from early times 55 Naraka or Narakasura does not seem to have originally been a Vaishnava The idea that he was the son of Vishnu is a much later one, as it is wanting in all the earlier texts like the Mbk and the Ram It is highly probable, on the other hand, that he was a Kapahka Shaiva According to the story of his birth, as given in Kahka-p chap 36-37, Naraka was born at the dead of night m the sacrificial ground of King Janaka of Videha, and immediately after his birth, began to cry, rolled away from there, and lay for some time on his back by placing his head on a human skull 63 It is interesting to note in this story that Naraka was conceived by his mother Prtluvi m an unusual condition during her monthly courses and (that his mother, as his nurse, reared him up and gave him instructions so that he might grow up as a human being jn mind and habits All these tend to show that he was not an Aryan by birth K L Barua is inclined to take the kings of the dynasty of Naraka to be of Dravidian origin 64 The facts that the Kapala (human skull) is a sign of the Kapahka Shaivas and that immediately after his birth Naraka was found with a skull under his head, tend to indicate that Naraka belonged originally to the Kapahka sect which was highly antagonistic to the Vedic VarnaSramadharma It may be that he was born and brought up in Shakta surroundings, and his connection with the Divine Boar seems to suggest his non Aryan origin The Aryans were tall and of bright complexion whereas the son of the Boar is expected to be a man of short stature, dark complexion and strong built body According to the Chinese traveller Yuan Chwang, the people of Kamarupa were ‘small of stature and black-looking 55 ’ So it is highly probable that Naraka was a local man of Kamarupa and not one from Videha, which, as the Kalika -p says, had been Aryamsed long before Naraka’s birth The term ‘Bhauma has been repeatedly used to refer to Naraka in the Mbh There may be a good deal of truth in the vie\V that Bhauma means local or born of the sod (bhumi) Evidently, he was a local man of Kamarupa, dark complexioncd and belonging perhaps to a Kirata or some other local tribe According to the hahka p, he defeated Ghataka of the Kirata tribe whose complexion was as bright as gold 58 So, Ghataka of the hahka p clearly belonged to the Mongolian tnbe But Naraka was a native of Kamarupa belonging presumably to a local tnbe, or another branch of the Kiratas, who were of dark complexion References to the black Kiratas are not wanting in our ancient literature Tor instance, the J\ r al)a-iaslra of Bharata prescribes that those actors, who arc to play the part of Kiratas, are generally to be painted black 57, and according to Bharavi’s Kiratarjuntja, Shiva in the guise of a Kirata appeared like a cloud 5 ® The author of the Purvapithika of Dandin’s Dasa kumara-canla places the Kiratas m the Vindhja terntor), the native tnbes of winch are mostl} black 5 ® In a work called Sakti-samgama iantra, the Kirata country is desenbed as being situated in the Vindhjas (kiratadeSo devesi vindhya Jade ca tisthati 80) It may be tint the predecessors of Naraka migrated from the Vindhyan territory or from some other place near about it, settled in Kamarupa and were regarded later on as original inhabitants of that place There seems, however, to be little doubt about the fact that Naraka himself was born in KSmarupa From the statement of the Brahma p we know that Naraka was born in Kokamukha-urtliain Kamarupa Thus, beginning from Naraka downwards to the earlier part of the reign of Dharmapala, Kapalika Shaivism, held sway all over Kamarupa and Assam. In recounting the sacred places of ancient Kamarupa, the Kahka-p. mentions fifteen places sacred to Shiva as against five sacred to Devi and five sacred to Vishnu 62

“The evidence furnished by the above sections of the Purana (i.e, Brahmo-p) prove beyond doubt that. the kokamukha tlrtha was m the Himalayan region on the northern fringe of Bengal ” B K. Banja in his Cultural History of Assam, vol T p 153, remarks "‘The reference to the KauhkX and Tnstota nvers as being m its neighbourhood d the site within the ancient boundary of Kamarupa.”

It is highly probable that some time during the long interval between Vajradatta and Pusyavarman a tidal wave in the shape of Vaishnava reform went over the country. During this long and dark period of the history of Kamarupa, attempts seem to have been made to bring all the non-Aryan and non-Vedic or anti-Vedic elements into the Aryan and Vedic fold by means of various innovations, and suitable stories were fabricated and included in books Naraka, definitely a non-Vedic and non-Vaishnava antagonist of the VarnaSramadharma, was connected with Vishnu in order to create a favourable field for Vaishnavism in Kamarupa. But the non-Aryan and non-Vedic inclinations of his mind were too strong to be wiped out totally It has been said in the Kdhka-p. that Naraka was well versed in the Vedas and devoted to the duties of the twice-born, and that Gautama performed his Kesa-vapana ceremony stnctly according to the Vedic rites. But one thing remains prominent that in spite of the Vedic Samskaras, Naraka reverted to his non-Vedic habits and tendencies which were natural to him Hence it is clear, that the flood of Vaishnavism was not very dishastrous for Shaivism that was deeply rooted in the hearts of the people of that place. It could not replace Shaivism but only acquired a temporary footing there. During this period of existence of Vaishnavism in Kamarupa, attempts were made to Aryanise the people and to trace the lineage of the kings of Kamarupa from an incarnation of Vishnu by giving out that Naraka, the cultural father of Kamarupa, was born of the Earth by Vishnu m his incarnation as the Great Boar 63 However, the Vaishnava hold on Kamarupa did not persist long Epigraphic, literary and other evidences indicate that at least from Bhaskaravarman’s time to the earlier part of the Dharma pala’s reign, Vaishnavism lost state support, the kings worslupped Mahesvara as their guardian deity, and there was a great spread of Kapahka Shaivism among the people It is this Shaivism (including Kapalika Shaivism) V hich, under the influence of Tantncism, was responsible for country wide corruption not favoured by the followers of Brahmanism Moreover, the influence of the Muslims which was an out come of the Muslim invasion, made the whole social structure of the country unbalanced At this critical stage of social disintegration came forward the brahmins In order to safeguard the interest of the society, they wrote this Dharma p and later on tried to make it a part of the widely read and universally accepted Padma-p They tried to free their country from undesirable elements and to re establish the Vedic Dharma This attempt of theirs proved to be successful, as Vaishnavism gamed fresh vigour in Kamarupa under the support of a ruling pnnce Dharmapala, whose second copper plate begins with an obeisance to God Narayana in the form of the Boar, 61 while in all the inscriptions of his predecessors and e\en in the first plate of himself the obeisance is to Lord Maheivara It wall perhaps not be unreasonable to presume, therefore, that Dharmapala changed his religious faith in his later life The period of his reign has been approximately fixed as 1090 1115 A D 65 If this date is correct, we can hold that at least from the beginning of the 12th century A D Vaishnavism gradually began to spread its influence which might have affected Bengal also A study of the Sena inscriptions shows that although Ballalasena and his predecessors were devotees of Shiva 60, Lakshmanasena and his successors began their inscriptions by invoking Narayana For instance, the Saktipur, Anulia, TarpandighiandMadhainagar copper-plates of Lakshmanasena, the Edilpur plate of Kesavasena and the Madhainagar and Sahitya Parisat copper-plates of ViSvarupasena begin with obeisance to Narayana 67 and in his Anulia and Madhainagar plates Lakshmanasena calls himself Parama-Vaishnava and ParamaNarasimha respectively 68. So, it is evident that from Lak§manascna’s time Vaishnavism began to receive statesupport in Bengal, and it may not be altogether improbable that this influx of Vaishnavism came from Kamarupa with which Bengal from time immemorial had a unique corelation of cultural movements. During the reign of the Pala and Sena kings, 5aivism spread widely over this country During Dharmapila s reign a four faced image of MahSdcva was installed In his Dfiagafpur grant, N5rJya<>apafa ay that he bestowed some gifts to Shiva-bhat (Iraka and his worshippers, ihc Plsupatas In his Deopara Inscription, Vijayasena invokes Shiva under the name of Sambhu His son BaJUlasena makes obeisance to Shiva under the names of Ardha nlruvara in the Naihati copper-plate grant and DhQqaji in the Rarrackpore copper-plate grant See N G Mazumdar, I nun pi ions of Bengal, III pp. 46, 61 and 71, also History of Benzol, \ol I p 405 It is interesting to note that Lakshmanasena applies the adjective Parama Vaishnava to his father in the Go\mdapur copper plate, although the latter distinctly calls himself Parama Mkhrlvara in the Nathan copper ptate grant. See N G Mazumdar, Insert.

The frequent occurrence of the word dharma in the inscriptions of the kings of Kamarupa has sometimes been taken to prove the prevalence of Buddhism there 60 and to account for all sorts of corruptions that struck at the very basis of the socio-religious structure of the country The description of Dharma, as found in the vs occurring in the Nidhanpur copper-plate ofBhaskaravarman, docs not certainly point to Buddhism as K. L. Barua thinks 70. As a matter of fact, none of the ideas, contained in this vs., has anything which is particularly Buddhistic. The word dharma has been defined in the Sabara-bhasya. of the Mimamsa-sulra as) a eva irej askarah sa eva dharma-fabdenocyate 71. There are also many references in the Af 6ft. to Dharma as a personal god 72. That the idea of Dharma is adrsta also was not unknown to the ancient Hindus, is evidenced by the following statement: Vcdaika-pram.lnagamjo’rthah punya-namadrsta-uScso dharmah. All the schools of Hindu Philosophy admit that Dharma is not seen but can only be inferred from its results. So, the word dharma as occurring in the said inscription undoubtedly refers to the Vamasramadharma of the Hindus. In the same inscription the following line occurs: sa jagad-udaya-kalpanastamayahetuna bhagavata harnala-sarpbhavcn5vaklrna-\arn3Srama-dharma-pravibhaga)a nirmitah 73. The occurrence of the word dharma at the very beginning of the inscription points to Bhaskann arman’s devotion to the Hindu faith. That by the word dharma the kings of KSmarupa meant the Vcdic VamaSramadharma, is shown by IndrapXla's first copper-plate also, in which there is the vs. ‘yasmin nrpe vmaya-vikrama-bhaji ja(te) samyagvibhakta caturasrama varna dharma 74 The occurrence of the name Tathagata m the same inscription has been taken by K L Barua and others’ 3 to point definitely to the prevalence of Buddhism in Kamarupa The relevant portion of the inscription runs thus ‘Uttarena tathagata-Jcaritaditya-bhattaraka-satka-iasana-bhavisa-bhu simni ksetrahstha-Sakhotaha-vrksa Pasupati-karita puskanm daksi(na)-patau ksetrali£-ca 7 V and it describes the northern boundary’ of the land given by Indrapala to a brahmin BeSapala by name It is clearly understood from this inscription that Tathagata is the name of a person 77 here who established an image of the Sun-god, for, in the following line there is a word paSupati which does not certainly refer to Shiva, the lord of animals, but is the name of person who cither owned a pond or caused it to be dug So the name Tathagata only proves that the Buddha and Buddhism were known in Kamarupa, and nothing more. The evidence of Kalhana’s Raja tarangim also is too meagre to be relied upon As stated by Kalhana, Meghavahana, the prince of KaSrmra, married Amrtaprabha, the daughter of the Kamarupa king, and the latter took her father's preceptor to her husband’s kingdom with her and there erected some stupas But one is unable to identify Amrtaprabha's father with any king of Kamarupa Thus, difficulty anses in believing all the statements of Kalhana in toto Moreover, Yuan Chwang expressly states 44 they (i e, the people of Kamarupa) worshipped the Devas, and did not believe in Buddhism So there had never been a Buddhist monastery in the land, and whatever Buddhists there were in it performed their acts of devotion secretly, the Deva-Temples were some hundreds in number, and the various systems had some myriads of professed adherents 78 n There is no reason to disbelieve the accounts of Yuan Chwang who actually travelled through the land unlike Kalhana who wrote from a place more than 1000 miles distant from Kamarupa 79 It is true that Bhaskaravarman treated the learned Chinese scholar with great respect, but this does not prove his inclination towards Buddhism It only show's the greatness of his heart The few sculptural representations of Buddha on stone and terra-cotta plaques, which ha\e been found in Kamarupa, need not be taken \cry seriously They might have been imported from outside. 60 We have indicated above where and how the Dharma p came into being and whj it was so called Although a comparatively late work, it has not come down to us un adulterated A critical study of its text shows that some new portions were added to it, some portions were abandoned, and some portions were altered The story of Andhaka, which is dealt with m chap 43, has been given again in chap 79 in connection with the glorification of Mangah Their beginnings and conclusions are the same In the former, Pulastya is the speaker, while m the latter the speaker is Vyasa who speaks to VaiSampayana and not to Bhisma It is, therefore, definite that one of these stones is spurious, and it seems that the latter is so, as it has imbibed 1 anlnc influence to a greater extent 81. Again, in chap 74 there is a dialogue between Satpjaya and Vyasa, but m vss I30IT of the same chap suddenly the speaker changes to Vaiiarppayana who continues in the same capacity in the following chaps and Samjaya is found no more Tins undoubtedly proves that it was revised by some person or persons Again, in chap 76 vss 18-20, Skanda desires to know from 6i\a, how the latter could incur sin by Brahma-hatyS, but Shiva is found to give in 45 vss ^ a pretty long reply which is wide of the mark Tins shows that either some portion of the question is spurious or the relevant portion of Shiva’s answer has been left out Further, vss 47-49 of chap 79 also may be regarded as spurious, for the dialogue between Brahma and Narada, which terminated in chap 46, cannot be expected in the above vss. Here a question arises as to how the Dharma p which, as we have already seen, was written in Kamarupa, could be incorporated into the Shrishti khanda, m which the Kamarupi^a brahmins have been denounced on two occasions In chap JO vss 14 16 it has been said that one, desirous of performing Sraddha ceremony, should seat a brahmin couple on a bed, mix with curd and milk a small piece of bone collected from the forehead of the deceased person and made into fine powder, and feed that couple with that mixture It further adds that this custom was seen among the first class Parvatiya brahmins B3 It should be men tioned here that although the relevant vss on this peculiar custom do not occur in the Bengal mss of the Shrishti khanda, all of which come from very late date, they have been quoted by Ballalasena 81 and Amruddhabhatta, of whom the latter remarks m his Haralata that by the word ‘Parvatiya the brahmins of Kamarupa have been meant 85 The second mention of the Kfiimrupiy a brahmins is found in chap 17, vss. 176-178a e, wherein it is said that SAvitrl cuncd the goddesses saying that Lakshmi would not live with them but would reside withnhc Mlccchas and the PArvaffyas. As to the occurrence of thcc two references in the Shrishti-hhanda it mas be said that these must have been added b\ the brahmins of MithilA who settled in Krtmarfipa and looked down upon the local brahmins The latter seem to have experienced better da vs under the rule of the Mlcccha dynasty and this was why the Maithila brahmins became jealous of them and referred to their customs with disrespect.

It is n teres ing to note that the cu tom of adm nistermg powdered bone of the deceased to the reap ents of beds was prevalent m the brahm a Zamindar fam lies of Mymcnsirjgh (now m East Pakistan) 1 11 the other day and these rec p enta were locally called Ifadg 1 (i.e. bone-ealmg) brahmins. Thu custom preva led in the Nagi community also cf The Statesman Calcutta thursday Apr l 2 19»3 p 1 col 8 (under the head ng Naga Chiefta n t pledge to give up Head hunt ng) The ch efta it of Tjawlaw leader of another head huntoig tr he and h s l eutenants touched a t ger s too h and chewed a b l of tin t ante tar t bones n an oath never to wage war again.

(2) THE BHUMI-KHAKDA.

In the course ofour remarks on the Devan’tgarl recension of the Spui-khan^a we Ime noted why the question of determining its proper place among other Khamjas appears to be a difficult task. There were, we have noticed, at least two contrary statements on this issue. Xo controversy, however, would arise with regard to the attribution of proper place to the Bhfimi-khanda. In all the printed editions of the Pa<itra-p.' i > as well as in all its available mss. both Ilengab and DnarrigarJ, the Khomi-khanda Jns been given the second place. 11m is also the ease with the available lists of the Klianda nr Parva division of the Ptdn<tp Hence, after our analysis of the Spthkhanda we propose 16 take up the Rhumi-Umula as our subject of study. There are strong grounds to believe that the present Bhumi-khanda which has come down to us was not the original one Very likely the whole of it has been revised, rewritten and recast Its apocryphal nature may be detected if one carefully goes through the original portion of the Sj-sti-khanda which seems to be earlier and more genuine In our analysis of the Shrishti-khanda we have tried to show what constitutes its earliest portion In that portion a short description of the contents of each Parva (Khanda) has been given There a short synopsis of the BhQmi-khanda also is found But, unfortunately this description of the subjectmatter of the Bhumi-khanda is in no way similar to the contents of the Bhumi-khanda as we see it today It 1 sh, however, true that the present Bhumi-khanda contains towards its end a summary of the contents discussed in it, but it should be noted that this summary is conspicuous by its absence in the older version thereof According to the Parva divisions of the Padma-p, which has been shown to be the earlier division, the second part is named Tirtha-parva which deals with plinatory geography 3 According to the Bengal mss also, the second Parva predominantly deals with a good number of sacred places 4 Moreover, the first chap of the Bengal ms of the Svarga-khanda states clearly that the Khanda previous to it, deals with the geography of the earth and has the serpent Shesha and the sage Vatsyayana ash the main interlocutor and hearer respectively From the latter Vyasa 13 appraised of the matter which he reports to the father of the Suta, from whom again the Suta comes to know of them. Again, the lines bhu\o mlnarp narniya' and ‘irutaip me bliagavan bhumch saipsthanam 7 ’clearly show that original!) the BliumMwhantJa of the iPedmi-p. dealt with the geography of the earth. Titus, to be precise, the BhumMhanda in its earlier stage Mas perhaps connected with the pianatory gcograph), sacred place as well as the gcograph) of the earth. But, in the present text of the Bhumt-hhanda, no such enumeration and glorification either of the sacred places or of the geographv of the earth is found. Hence, it may perhaps be presumed that the original BhumMehantfa which dealt with these things has been totally lost, and has been replaced by a new one, which is nothing but a collection of several stories. The name BhumMriianda along with the names Svarga-hhanda and IMtnla-khan^ta may create an impression that its contents were concerned with the earth while those of the other two with the hcaxcu aud the nether regions rcspcctivclv. This serves to confirm our contention that the whole of the present Bhumi-khanda is the product of a latrr age. Moreover, the present Bhumikhan<)a docs not contain anywhere the names of VatsySyana and Seja as the hearer and the intcrlocuror. This is also suggestive of the apocr>phal nature of the present Bhumt-khanda, and it is almost sure that the BhtimMJtanda winch discussed the geography of the earth and heaven at least preerded the present Bhumh Lhanda\ But, even the present form of the Phumt-khand is the product of different hands at different As in the other Pur3nas, this Khanka also bran the stamp of interisolation which may be delected by a critical analysis of the whole of it For example, the fortymth chap, contain a vs f. which informs us that the Gltavidv.'ldhara reports to Indra that he (Gitavidyadhara) has performed what he has been asked to do by his master Indra But actually, we do not find any reference to such request or order given to the Gitavid>adhara by Indra Thus it is obvious that either some coherent portions of this section have been lost or the whole of the Gitavidyadhara episode is a later fabrication Moreover, it is to be noted that the story of Prthu and Vena nhich commences independently from the beginning of the twentysixth chap and runs to the end has no link with the previous chaps One can, therefore, easily understand these two broad divisions of the Bhumi khanda viz, (i) the first twenty five chaps and, (») that from chap 26 to the end. A penetrating search will show that the second portion has been added later as all evidences of a late period are discernible in this section The thirtysixth chap bears traces of the later phase of development of the Jama Philosophy The distinct mention of the name Turuska (which undoubtedly points to the Mohammedans who invaded India about the 9th century A D) which is found in the seventyeighth chap 10 also points to that conclusion A later idea of the origin of Suta, which does not coincide with that as given m the Vayu-p, has been discussed in the twentyseventh chap 11 Moreover, undue importance has been given in that portion to the Tulasi plant, which is unmistakably a mark of its later origin. The fixing of the date of the first section, l e, the first twentyfive chaps, will enable us to fix the date of the second part In the first section 52 Buddha has been mentioned as one of the incarnations of Vishnu It is generally accepted that Buddha came to be recognised as an incarnation of Vishnu from about 550 AD 13 Moreover, at the very beginning of the first chap of this Khanda, the sages ask Suta to narrate that story in the Puranas in which Prahlada is said to have worshipped KeSava when the former was only five years of age 14 It appears from this, that the author was referring to the Bhagavata p where alone the age of Prahlada along with his story has been given 15 Now the date of the Bhagaiata p has been fixed as the sixth century AD 18 Thus we see that the upper limit cannot go be>ond the seventh century AD as at least a span oflOO years should be allowed to intervene between the two works, viz, more recent and the older one, and it is highly probable that it was written between 700 and 800 A. D. The argument that Bhumi khanda should be placed in a still later period as none of the Smriti writers quote from it is not sufficiently convincing The Smriti writers generally quote those texts of the Puranas where Smarta rites and customs are delineated, as such texts help them m establish ing their point of view But this portion of the Bhumi khanda does not contain any element which can be utilised by any Smriti writer It is nothing more than a mere collec tion of some legendary tales So it is more probable that the Smriti writers, although they were conversant with the existence of this portion of the Bhumi khanda did not make use of it as they did not find anything helpful for their purpose. As for the date of the second portion, we think, we shall have little difficulty to reach a decision \Ve have already referred to the Turuskas as mentioned in this portion They had come to India about the ninth century AD So the con elusion is irresistible that the same happens to be the lower limit. We shall now show on the strength of the Bengal mss of the Bhumi khanda of the Padma p that the Bengal or East Indian text of the Bhumi khanda was an earlier one in comparison with the De\ anagan text of it The former see ms not to be acquainted with the Bhagavata p, as there is no mention about Prahlada’s age The necessary lines read as ‘yat-svadharma-hitenapP for ‘panca-varsanvitcnapi of the Devanagari text The Bengal ms contains an earlier set of hearer and interlocutor who were Shesha the serpent and the sage Vatsyayana respectively It contains some description of the geography of the earth (which justify the name Bhumikhanda), and of some sacred places which include first of all Puskara — the abode of Brahma and some eastern tirthas such as the Karatoya As Puskara has been very much glorified and as it has been given the first place among all the tirthas, it can perhaps be safely remarked that the original Bhumi-khanda was written in East India during the eighth century by the Brahma-worshippers We have shown before that at that period East India was a stronghold of Brahmaism Later, the Bhumi-khanda was taken up by the Vaishnavas who must have been residing in the territories near the river Reva (as it appears from the innumerable glorifications of that river in the printed texts all of which come from the Devanagari recension) The Vaishnavas had probably eliminated the geographical features and the glorifications of Puskara and other places associated with it, invented some stones glorifying the Jangama tirtha (not the Sthavara-tirthas of the Bengal mss) and incorporated them therein Their attempt proved successful The influence of the Brahma-worshippers in the original Bhumi khanda disappeared and gradually the people took this Khanda as a Vaishnava work delineating and eulogising the glorifications of Vishnu.

(3) THE SVARGA-KHANDA (ADI a BRAHMA-KHANDA)

According to the Vang ed of the Padma p the Svarga khanda occupies the third place It is quite natural that after carefully and elaborately delineating the Bhumi, i e, the earth, the narration of the Svarga (the upper land or the heaven) has been taken up But unfortunately, as we observed in our first chap., in the Anss. cd. of the Padma-p. no such division bearing the name Svarga is found. Incidentally it should be pointed out that the whole of the contents of the Svarga-khanda is found in the Anss. cd- also. In the latter ed. the Adi and the Brahma-khanda combined together constitute the Svarga-khanda of the Vang. ed. Thus to be precise — that part of the Padma-p. which has been published under the title Svarga-khanda by the Vang. Press is nothing but the combination of the Adi and the Brahma-khanda as found in the Anss. cd. In the Venkat. ed. of the Padma-p the Svarga-khanda of the Padma-p. is named the Adi-khanda. Although the Venkated. docs not contain the name of the Brahma-khanda it retains the whole of it. The name Svarga-khanda appears to be more correct and authentic because the Patala-khanda which follows it categorically mentions that it is the Svarga-khanda which immediately precedes the Patala-khanda. 1 There arc two passages in the Adi-khanda of the Anss. and Venkat. editions where Adi-khanda and Adi-sarga have been mentioned The vss. in question arc as follow's: tatradav-adi-khandaip syad bhumi-khandarp tatah param/ 2 and: adi-sargam-aharp tuvat kathayami dvijottamih / jiiiyatc vena bhagavan paramatma sanatanah// Here Khanda and Sarga obviously refer to the same thing, both meaning portion or part. But the mss consulted for preparing the Anss. cd are not unanimous in their readings of the first passage. Two mss marked Mia and n clearly read Spti-Uiandam instead of Adikhnndam. According to them the reading is as follows: tatradau sp^i-kliardarp syftd bhfuni-Uiandarp tatah param 4

The Vang. cd. of the Svarga-khanda reads adya svargam-aham tavat Kathayami dvijottamah instead of adisargam-aham tavat 5. The N6radt}ap. speaks of the Svarga-khanda and gives its summary. The Adi-khanda which as we have observed comprises the first part of the Svarga-khanda, can neither claim to be a genuinely original work nor can it command a respectable antiquity. The Adi-khanda in its Anss. cd. contains sixtytwo chaps. 6 among which at least tliirtysix chaps, arc in common with some of the other Puranas. The following analysis may be helpful in this connection.

The first part of the Vaåg ed of the Svatga k) anda seluch corresponds to the Adl khanda of the Anss ed consists of thirtythree chaps Generally one chap Of the Vang ed coveß two chaps of the Anss ed Hence the anomaly in the numbermg of the chaps may not be seriously considered. In the Afatsya2 context the speaker here while the Adl khaoda has Nårada as the speaker Some vss (twelve) of chap 187 of the MatyaP are not found m chap 14 of the Adi khanda Chap 188 algo contatns more vss than chap 15 The difference bet Ln the name of the speaker only Natada as the prmopal speaker tn that portton of the AdL khandag while the Uttara khava has Dattatreya as its speaker The first ntneteen vss {except vs I) o! the thirtyfourth chap of the Rutma constitute the thxrtyseventh chap of the Ad' khapda to The last five vss or chap 112 where there a reported speech o? Nandlkeivara and Suta In the Maeya are not found an the AdL khapda chap 49

It has been held that as regards these common chaps the Adi-khanda is the borrower 12. These portions of the Matsja-p. and the KBrma-p. from which identical vss. have been taken and used in the Adi-khanda may be dated most probably between 800 and 1200 A.D 13 Thus the Adikhanda or the first part of the Svarga-khanda of the Padma-p. cannot be supposed to have been written or compiled before 1000 A.D. Its more recent origin is also proved by the mark of later Vaishnavism dealt with in it. Nowhere in this Khanka such stamps of early production as invocation to Brahma, glorifications of Brahma-worshippers arc observable. On the contrary a few chaps, towards the end deal profusely with Vishnu-bhaktt and high respect to Vishnu and Vaishnava Although, perhaps the main theme of thisKhanda is to offer a glimpse into the mystery of the creation of the universe and to delineate the glories of a number of sacred places and rivers, the whole of it is redolent of Vishnu-mahatmya. 11 For a comparatne study the fottovvmg analysis of the different chap, of the Ad) khan^a and the Karma p is given Adi khapda 51 karma-) oga kathanam^ Kurma 12 brihmanlnlm upanayanidibmu»yogo nSma etc t 52 karma yoga kathanam^-AVmuJ ]3 brahmavidySyim leamanildikarma-yogo nima etc „ 53 karma yoga kalhanam hunrui 14 brali mavdyS) Sip vedldhya yanSdi kramantyamo ninu etc p 54 dliarma kathanam — Aumid 15 brahmatid)5) 5rp dharmidli) J>o nlma etc „ 55 d! arma-kathanam«» Kuma 16 brahmavid)S)Jm liandcira myama-dl armo n5ma etc fP 56 bhakjylbhikiya nivama kathanam 17 bhakf> a khAlfya-n injay o rim tic „ 57 gphajiha-dharma nirnaya Kurma 26 brahmarwi) 5yin dinadharmSdi kaihanam nima etc 58 vinaprasthiframiclra kithanam^ Karma 27 brahmavklylyirp vlnaprasthiiraTTva-dharmo nima etc „ 59 arma mrfipanam^/arn»4 23 brahmavid)!)Jrp yatiDharmo nima etc Pf 60 No name of the chap. U found us the cotopl»on Kirw 29 brahmav»dyJ)lEti yatidharmo nlma etc. The latter part of the shvarga-khanda,i e,Brahma-khanda of the Anss ed is a \er> short one consisting of twentysix chaps only It deals mainly with the glorification of Vishnu It is said that the people who besmear a Vishnutcmple with cow dung or even accidentally apply some lime over the walls of it or make the gift of a lamp to it go straight to the Vishnu-loka It is also concerned with the descriptions of the merits of observing some Vaishnava vratas such as, Jay^antl-vrata, Guruvara-vrata, Hari janmostaml and R3dhastami-vrata, Hanvasara-vrata, Vishnupaficakavrata and the worship of Vishnu on the full-moon day Moreover, the water winch is being touched by Vishnu's feet has been highly spoken of and glonficd, the month of KartUka and the Tulasi plant ha\e been eulogised Various stories have been told about the merits of observing these vratas or festivals The author or compiler of this Khanda while describing the Radhastami (the birthday festival of Radha) has narrated the story of Sarmidra manthana The brahmins have been glonficd in more than one chap. There are unmistakable signs in this Khanda from which it can be safely remarked that it comes from a very late date The whole or the chap 7 deals profusely with the birthday festival of Radha, the eternal female consort of Krishna Moreover, here and there we come across references to Radha w’orship and glorification of Radhii-worshippers The term ‘consort or beloved of Han’ (han pnya) has been given to the Tulasi plant which has been highly eulogised The garland of Tulasi can remove all sins 11 One who holds the Tulasi garland on his neck, is respected even by the denizens of the heaven 15 Similar other observations on the Tulasi plant are found Some chaps speak highly of the gifts of lamps to the shrines of Vishnu All these are unmistakable stamps of a very' late age The ancient works like the Mbh, Ram, Hanvamsa md the earlier Puranas do not anywhere mention the name of Radha or the Radha-worshippers. The sect of 15 the Radha-vallabhins who look at Radha as the eternal Sakti, it is held, arose not before the 16th century A.D. From the inscriptional records it is known that the gift of lamps to the temples became popular in southern India from about the end of the ninth centur) A D. 17 All these considerations point to the late date of composition of this Khan da. This is supported by the evidence of the Nibandha-writers who have nowhere taken in their writings any passage from this Khanda nor have evenreferred to it although some portions of this Khanda might have ' suited their purpose. The Naradi)a-p. y however, includes its contents. 18 Hence it can be said that this Brahma-khanda is not later than 1400 A.D Thus w T e find that the approximate date of the Svarga-khanda of the Padma-p, may be fixed between 1200 and 1400 A.D.

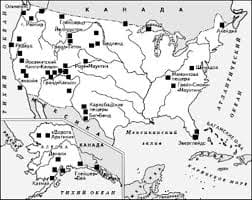

ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|