|

|

The problem of gender in nounsСтр 1 из 3Следующая ⇒ The problem of gender in nouns

The category of gender Traditionally gender is a lexical category of nouns as there are no gramatical markers - Fillmore, Palmer

Professor Blokh - he defines nouns into - person nouns (feminine/masculine) - non-person nouns (animate/inanimate)

Lexical means to express gender in English: - pronominal correlations - the use of personal pronouns he, she, it (man can be substituted by 'he') - word composition: he-cat, she-cat, billy-goat, nanny-goat, jack-ass, jenny-ass - personification - a stylistic device when human properties are ascribed to lifeless things: the Moon - she (smth unpredictable, beautiful), a ship - she, a car - she

The common gender - doctor, professor, friend

The category of determination It is a grammatical category - the gram meaning of definitness/indefinitness is demonstrated through the article It is a binary privative opposition the:: zero article, a/an the meaning of identification or non-identification

Tr-lly the articke and the niun is a phrase, but some scholars (Ilyish, Blokh) consider such units to be analytical forms where the article is a special type of grammatical auxiliary

The problem of gender in English nouns. There is a constant contradiction between the presentation of gender in English. Blokh: The category of gender is expressed in English by the obligatory correlation of nouns with the personal pronouns of the 3rd person. It’s strictly oppositional, formed by 2 oppositions hierarchically related.1.This opposition functions in the whole set of nouns dividing them into person (human) (strong) and non-person (non-human) nouns (weak).2. The other opposition functions in the subset of person nouns only dividing them into masculine and feminine. The cases of reductions:1.Non-person & their substitute are used in the positions of neutralization.2.Great number of nouns are capable for expressing both female & masculine person genders. Ex: person, parent, friend have a common gender. In plural all genders - neutralized. Nouns can show the sex of their referents lexically ex: boy-friend, girl-friend or with the help of suffixes –ess (mistress). Categories of gender in English is semantic because it reflects the actual features of the named objects, but the semantic of the category doesn’t in the least make it into non-grammatical.

The problem of case in nouns The category of case Tr-ly it shows relations of the niun to other words in the sentence, it is expressed by the binary privative opposition: Common (unmarked, weak) - Genetive (marked, strong). It is a morphological

Non-morphological approaches to the category of case -the theory of positional cases (John Nesfield, Max Deutschbein): cases are distinguished by the position of the noun in the sentence: the Nominative case, the Vocative case, Dative, Accusative Nom - subject, precedes the verb: rain falls Vocative - the noun is in a direct adress, separated by commas Acc - direct object, follows the verb (he saw a dog) Demerit: it substitutes the functional charecteristics of the sentence part for the morphological features: the case is a morphological category, it should be marked by a gramatical signal, but here it is marked by syntactical positions, rather then the form of the noun

-the theory of analytical case forms (George Curme): case relations are expressed by prepositions or by their absense: 4 cases - Nominative - marked by the absense of the preposition -Accusative - it follows a verb used as a direct object, marked by the absense of the preposition -Dative - marked by the preposition 'to' -Instrumental 'with' Demerit: the number of case forms are unlimited, there be a lot of cases, as there are a lot of prepositions

- the English noun has lost the category of case (Professor Vorontsova, pr Ezhkova, pr Mukhin) the grounds: 1) the -'s inflection may be added not only to separate nouns, but to the group of words (the group genetive) - Tom and Mary's house, Henry Sweet: the man I saw yesterday's son - the inflection is added to the whole subordinate clause 2) there is a parallism of the constructions with the Common case and the Gen case, no difference in the meaning, or it is very slight London streets (is more general)- London's streets (such as... - the meaning is more specified) with person nouns we can use either the Gen case or an of-phrase the face of Irene (a rheme is 'of Irene') - Irene's face (we speak about the part of the body, not its owner) Professor Mukhin speaks of 's i flection as a particle denoting posession The form words in English FORM WORDS trad-ly they are devoid of a lex meaning, no syntactic function. They are closed systems, because no new prepositions or conjunctions an so on appear

Problems - the number of form words is debatable some scholars (Smirnitskiy, Sweet) consider link verbs to belong to form words as well 'he became a teacher' Henry Sweet distinguishes full form words (he became Prime minister - it combines the full meaning of change with the gram function of the form word 'to be') and empty form words (the Earth is round - it doesn't presuppose the meaning of change, it emphasises only the form function of the verb 'to be') He says that sometimes 'to be' may be used as a full form word with the meaning of change: 'Troy is no more' - there is the meaning of change

- homonymous parts of speech 'some' is used as indef pronoun (then it has a strong stress - 'some people think') and a form word ('give me some more bread' has a weak stress)

-Jespersen 'the philosophy of grammar' combines adverbs, prepositions, conjunctions and interjections as one part of speech - 'particles' on the basis they are unchangeable in their form

-Charles Fries - gives 15 groups of function words - group a (includes all the words in the position of the definite article - no, some) group b (modal words)

- the problem of the meaning of form words trad-ly they are devoid of lex meaning, fulfill only gram function But Ilyish considers form parts of speech to have their own lex meaning - the book is in/on the table - whether they are words of morphemes, i.e. the variety of affixes? trad'ly they are words Smirnitskiy - 'I gave an apple to the boy' - the function is that of a morpheme, the same function as the case inflections in Russian Barkhudarov speaks on double nature of form parts of speech - formally they are words, but functionally they are morphemes The IC method The IC method, introduced by American descriptivists, presents the sentence not as a linear succession of words but as a hierarchy of its ICs, as a ’structure of structures’. Ch. Fries, who further developed the method proposed by L.Bloomfield, suggested the following diagram for the analysis of the sentence which also brings forth the mechanism of generating sentences: the largest IC of a simple sentence are the NP (noun phrase) and the VP (verb phrase), and they are further divided if their structure allows.

Layer 3 The recommending committee approved his promotion. Layer 2 Layer 1

The deeper the layer of the phrase (the greater its number), the smaller the phrase, and the smaller its ICs. The resulting units (elements) are called ultimate constituents (on the level of syntax they are words). If the sentence is complex, the largest ICs are the sentences included into the complex construction. The diagram may be drawn somewhat differently without changing its principle of analysis. This new diagram is called a ‘candelabra’ diagram.

The man hit the ball. S If we turn the analytical (‘candelabra’) diagram upside down we get a new diagram which is called a ‘derivation tree’, because it is fit not only to analyze sentences, but shows how a sentence is derived, or generated, from the ICs. The IC model is a complete and exact theory but its sphere of application is limited to generating only simple sentences. It also has some demerits which make it less strong than transformational models, for instance, in case of the infinitive which is a tricky thing in English. I.Causality "Itsy Bitsy spider climbing up the spout. Down came the rain and washed the spider out." The event of "raining" causes the event of "washing the spider out" because it creates the necessary conditions for the latter; without the rain, the spider will not be washed out. II.Enablement "Humpty Dumpty sat on the wall, Humpty Dumpty had a great fall." The action of sitting on the wall created the sufficient but not necessary conditions for the action of falling down. Sitting on a wall makes it possible but not obligatory for falling down to occur. III.Reason "Jack shall have but a penny a day because he can't work any faster." In contrast to the rain which causes Itsy Bitsy spider to be washed out, the slow working does not actually cause or enable the low wage. Instead, the low wage is a reasonable outcome; "reason" is used to term actions that occur as a rational response to a previous event. IV.Purpose "Old Mother Hubbard went to the cupboard to get her poor dog a bone." In contrast to Humpty Dumpty's action of sitting on the wall which enables the action of falling down, there is a plan involved here; Humpty Dumpty did not sit on the wall so that it could fall down but Old Mother Hubbard went to the cupboard so that she could get a bone. "Purpose" is used to term events that are planned to be made possible via a previous event. V.Time "Cause", "enablement" and "reason" have forward directionality with the earlier event causing, enabling or providing reason for the later event. "Purpose', however, has a backward directionality as the later event provides the purpose for the earlier event. More than just a feature of texts, coherence is also the outcome of cognitive processes among text users. The nearness and proximity of events in a text will trigger operations which recover or create coherence relations. "The Queen of Hearts, she made some tarts; The Knave of Hearts, he stole the tarts; In the explicit text, there is a set of actions (making, stealing and calling); the only relations presented are the agent and the affected entity of each action. However, a text receiver is likely to assume that the locations of all three events are close to one another as well as occur in a continuous and relatively short time frame. One might also assume that the actions are meant to signal the attributes of the agents; the Queen is skilled in cooking, the Knave is dishonest and the King is authoritative. As such, coherence encompasses inferencing based on one's knowledge. For a text to make sense, there has to be interaction between one's accumulated knowledge and the text-presented knowledge. Therefore, a science of texts is probabilistic instead of deterministic, that is, inferences by users of any particular text will be similar most of the time instead of all of the time. Most text users have a common core of cognitive composition, engagement and process such that their interpretations of texts through "sensing" are similar to what text senders intend them to be. Without cohesion and coherence, communication would be slowed down and could break down altogether. Cohesion and coherence are text-centred notions, designating operations directed at the text materials. Intentionality [edit] Intentionality concerns the text producer's attitude and intentions as the text producer uses cohesion and coherence to attain a goal specified in a plan. Without cohesion and coherence, intended goals may not be achieved due to a breakdown of communication. However, depending on the conditions and situations in which the text is used, the goal may still be attained even when cohesion and coherence are not upheld.

Even though cohesion is not maintained in this example, the text producer still succeeds in achieving the goal of finding out if the text receiver wanted a piggyback. Acceptability [edit] Acceptability concerns the text receiver's attitude that the text should constitute useful or relevant details or information such that it is worth accepting. Text type, the desirability of goals and the political and sociocultural setting, as well as cohesion and coherence are important in influencing the acceptability of a text. Text producers often speculate on the receiver's attitude of acceptability and present texts that maximizes the probability that the receivers will respond as desired by the producers. For example, texts that are open to a wide range of interpretations, such as "Call us before you dig. You may not be able to afterwards', require more inferences about the related consequences. This is more effective than an explicit version of the message that informs receivers the full consequences of digging without calling because receivers are left with a large amount of uncertainty as to the consequences that could result; this plays to the risk averseness of people. Informativity [edit] Informativity concerns the extent to which the contents of a text are already known or expected as compared to unknown or unexpected. No matter how expected or predictable content may be, a text will always be informative at least to a certain degree due to unforeseen variability. The processing of highly informative text demands greater cognitive ability but at the same time is more interesting. The level of informativity should not exceed a point such that the text becomes too complicated and communication is endangered. Conversely, the level of informativity should also not be so low that it results in boredom and the rejection of the text. Situationality [edit] Situationality concerns the factors which make a text relevant to a situation of occurrence. The situation in which a text is exchanged influences the comprehension of the text. There may be different interpretations with the road sign

However, the most likely interpretation of the text is obvious because the situation in which the text is presented provides the context which influences how text receivers interpret the text. The group of receivers (motorists) who are required to provide a particular action will find it more reasonable to assume that "slow" requires them to slow down rather than referring to the speed of the cars that are ahead. Pedestrians can tell easily that the text is not directed towards them because varying their speeds is inconsequential and irrelevant to the situation. In this way, the situation decides the sense and use of the text. Situationality can affect the means of cohesion; less cohesive text may be more appropriate than more cohesive text depending on the situation. If the road sign was "Motorists should reduce their speed and proceed slowly because the vehicles ahead are held up by road works, therefore proceeding at too high a speed may result in an accident', every possible doubt of intended receivers and intention would be removed. However, motorists only have a very short amount of time and attention to focus on and react to road signs. Therefore, in such a case, economical use of text is much more effective and appropriate than a fully cohesive text. Intertextuality [edit] Intertextuality concerns the factors which make the utilization of one text dependent upon knowledge of one or more previously encountered text. If a text receiver does not have prior knowledge of a relevant text, communication may break down because the understanding of the current text is obscured. Texts such as parodies, rebuttals, forums and classes in school, the text producer has to refer to prior texts while the text receivers have to have knowledge of the prior texts for communication to be efficient or even occur. In other text types such as puns, for example "Time flies like an arrow; fruit flies like a banana', there is no need to refer to any other text. Main contributors[edit] Robert-Alain de Beaugrande [edit] Robert-Alain de Beaugrande was a text linguists and a discourse analyst, one of the leading figures of the Continental tradition in the discipline. He was one of the developers of the Vienna School of Textlinguistik (Department of Linguistics at the University of Vienna), and published the seminal Introduction to Text Linguistics in 1981, with Wolfgang U. Dressler. He was also a major figure in the consolidation of critical discourse analysis.[14] Application to language learning[edit] Text linguistics stimulates reading by arousing interest in texts or novels. Increases background knowledge on literature and on different kinds of publications. Writing skills can be improved by familiarizing and duplicating specific text structures and the use of specialized vocabulary.[13]

Pragmatics Pragmatics is a subfield of linguistics and semiotics which studies the ways in which context contributes to meaning. Pragmatics encompasses speech acttheory, conversational implicature, talk in interaction and other approaches to language behavior in philosophy, sociology, linguistics and anthropology.[1]Unlike semantics, which examines meaning that is conventional or "coded" in a given language, pragmatics studies how the transmission of meaning depends not only on structural and linguistic knowledge (e.g., grammar, lexicon, etc.) of the speaker and listener, but also on the context of the utterance, any pre-existing knowledge about those involved, the inferred intent of the speaker, and other factors.[2] In this respect, pragmatics explains how language users are able to overcome apparent ambiguity, since meaning relies on the manner, place, time etc. of an utterance.[1] The ability to understand another speaker's intended meaning is called pragmatic competence. [3][4][5] Ambiguity[edit] Main article: Ambiguity The sentence "You have a green light" is ambiguous. Without knowing the context, the identity of the speaker, and his or her intent, it is difficult to infer the meaning with confidence. For example: · It could mean that you have green ambient lighting. · It could mean that you have a green light while driving your car. · It could mean that you can go ahead with the project. · It could mean that your body has a green glow. · It could mean that you possess a light bulb that is tinted green. Similarly, the sentence "Sherlock saw the man with binoculars" could mean that Sherlock observed the man by using binoculars, or it could mean that Sherlock observed a man who was holding binoculars (syntactic ambiguity).[6] The meaning of the sentence depends on an understanding of the context and the speaker's intent. As defined in linguistics, a sentence is an abstract entity — a string of words divorced from non-linguistic context — as opposed to an utterance, which is a concrete example of a speech act in a specific context. The closer conscious subjects stick to common words, idioms, phrasings, and topics, the more easily others can surmise their meaning; the further they stray from common expressions and topics, the wider the variations in interpretations. This suggests that sentences do not have meaning intrinsically; there is not a meaning associated with a sentence or word, they can only symbolically represent an idea. The cat sat on the mat is a sentence in English; if you say to your sister on Tuesday afternoon, "The cat sat on the mat," this is an example of an utterance. Thus, there is no such thing as a sentence, term, expression or word symbolically representing a single true meaning; it is underspecified (which cat sat on which mat?) and potentially ambiguous. The meaning of an utterance, on the other hand, is inferred based on linguistic knowledge and knowledge of the non-linguistic context of the utterance (which may or may not be sufficient to resolve ambiguity). In mathematics with Berry's paradox there arose a systematic ambiguity with the word "definable". The ambiguity with words shows that the descriptive power of any human language is limited. Referential uses of language[edit]

When we speak of the referential uses of language we are talking about how we use signs to refer to certain items. Below is an explanation of, first, what a sign is, second, how meanings are accomplished through its usage. A sign is the link or relationship between a signified and the signifier as defined by Saussure and Huguenin. The signified is some entity or concept in the world. The signifier represents the signified. An example would be: "Santa Claus eats cookies." In this case, the proposition is describing that Santa Claus eats cookies. The meaning of this proposition does not rely on whether or not Santa Claus is eating cookies at the time of its utterance. Santa Claus could be eating cookies at any time and the meaning of the proposition would remain the same. The meaning is simply describing something that is the case in the world. In contrast, the proposition, "Santa Claus is eating a cookie right now," describes events that are happening at the time the proposition is uttered. Semantico-referential meaning is also present in meta-semantical statements such as: Tiger: carnivorous, a mammal If someone were to say that a tiger is an carnivorous animal in one context and a mammal in another, the definition of tiger would still be the same. The meaning of the sign tiger is describing some animal in the world, which does not change in either circumstance. Indexical meaning, on the other hand, is dependent on the context of the utterance and has rules of use. By rules of use, it is meant that indexicals can tell you when they are used, but not what they actually mean. Example: "I" Whom "I" refers to depends on the context and the person uttering it. As mentioned, these meanings are brought about through the relationship between the signified and the signifier. One way to define the relationship is by placing signs in two categories: referential indexical signs, also called "shifters," and pure indexical signs. Referential indexical signs are signs where the meaning shifts depending on the context hence the nickname "shifters." 'I' would be considered a referential indexical sign. The referential aspect of its meaning would be '1st person singular' while the indexical aspect would be the person who is speaking (refer above for definitions of semantico-referential and indexical meaning). Another example would be: "This" A pure indexical sign does not contribute to the meaning of the propositions at all. It is an example of a ""non-referential use of language."" A second way to define the signified and signifier relationship is C.S. Peirce's Peircean Trichotomy. The components of the trichotomy are the following: 1. Icon: the signified resembles the signifier (signified: a dog's barking noise, signifier: bow-wow) These relationships allow us to use signs to convey what we want to say. If two people were in a room and one of them wanted to refer to a characteristic of a chair in the room he would say "this chair has four legs" instead of "a chair has four legs." The former relies on context (indexical and referential meaning) by referring to a chair specifically in the room at that moment while the latter is independent of the context (semantico-referential meaning), meaning the concept chair. Non-referential uses of language[edit] Silverstein's "pure" indexes [edit] Michael Silverstein has argued that "nonreferential" or "pure" indices do not contribute to an utterance's referential meaning but instead "signal some particular value of one or more contextual variables."[10] Although nonreferential indexes are devoid of semantico-referential meaning, they do encode "pragmatic" meaning. The sorts of contexts that such indexes can mark are varied. Examples include: · Sex indexes are affixes or inflections that index the sex of the speaker, e.g. the verb forms of female Koasati speakers take the suffix "-s". · Deference indexes are words that signal social differences (usually related to status or age) between the speaker and the addressee. The most common example of a deference index is the V form in a language with a T-V distinction, the widespread phenomenon in which there are multiple second-person pronouns that correspond to the addressee's relative status or familiarity to the speaker. Honorifics are another common form of deference index and demonstrate the speaker's respect or esteem for the addressee via special forms of address and/or self-humbling first-person pronouns. · An Affinal taboo index is an example of avoidance speech that produces and reinforces sociological distance, as seen in the Aboriginal Dyirbal language of Australia. In this language and some others, there is a social taboo against the use of the everyday lexicon in the presence of certain relatives (mother-in-law, child-in-law, paternal aunt's child, and maternal uncle's child). If any of those relatives are present, a Dyirbal speaker has to switch to a completely separate lexicon reserved for that purpose. In all of these cases, the semantico-referential meaning of the utterances is unchanged from that of the other possible (but often impermissible) forms, but the pragmatic meaning is vastly different. The performative [edit] Main articles: Performative utterance and Speech act theory J.L. Austin introduced the concept of the performative, contrasted in his writing with "constative" (i.e. descriptive) utterances. According to Austin's original formulation, a performative is a type of utterance characterized by two distinctive features: · It is not truth-evaluable (i.e. it is neither true nor false) · Its uttering performs an action rather than simply describing one However, a performative utterance must also conform to a set of felicity conditions. Examples: · "I hereby pronounce you man and wife." · "I accept your apology." · "This meeting is now adjourned." Jakobson's six functions of language [edit] Main article: Jakobson's functions of language

The six factors of an effective verbal communication. To each one corresponds a communication function (not displayed in this picture).[11] Roman Jakobson, expanding on the work of Karl Bühler, described six "constitutive factors" of a speech event, each of which represents the privileging of a corresponding function, and only one of which is the referential (which corresponds to the context of the speech event). The six constitutive factors and their corresponding functions are diagrammed below. The problem of gender in nouns

The category of gender Traditionally gender is a lexical category of nouns as there are no gramatical markers - Fillmore, Palmer

Professor Blokh - he defines nouns into - person nouns (feminine/masculine) - non-person nouns (animate/inanimate)

Lexical means to express gender in English: - pronominal correlations - the use of personal pronouns he, she, it (man can be substituted by 'he') - word composition: he-cat, she-cat, billy-goat, nanny-goat, jack-ass, jenny-ass - personification - a stylistic device when human properties are ascribed to lifeless things: the Moon - she (smth unpredictable, beautiful), a ship - she, a car - she

The common gender - doctor, professor, friend

The category of determination It is a grammatical category - the gram meaning of definitness/indefinitness is demonstrated through the article It is a binary privative opposition the:: zero article, a/an the meaning of identification or non-identification

Tr-lly the articke and the niun is a phrase, but some scholars (Ilyish, Blokh) consider such units to be analytical forms where the article is a special type of grammatical auxiliary

The problem of gender in English nouns. There is a constant contradiction between the presentation of gender in English. Blokh: The category of gender is expressed in English by the obligatory correlation of nouns with the personal pronouns of the 3rd person. It’s strictly oppositional, formed by 2 oppositions hierarchically related.1.This opposition functions in the whole set of nouns dividing them into person (human) (strong) and non-person (non-human) nouns (weak).2. The other opposition functions in the subset of person nouns only dividing them into masculine and feminine. The cases of reductions:1.Non-person & their substitute are used in the positions of neutralization.2.Great number of nouns are capable for expressing both female & masculine person genders. Ex: person, parent, friend have a common gender. In plural all genders - neutralized. Nouns can show the sex of their referents lexically ex: boy-friend, girl-friend or with the help of suffixes –ess (mistress). Categories of gender in English is semantic because it reflects the actual features of the named objects, but the semantic of the category doesn’t in the least make it into non-grammatical.

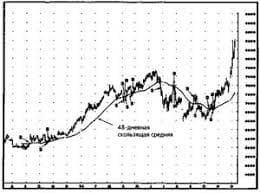

ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|