|

|

Specially Built Training CentersWhat about specially built search and rescue dog training centers? Are these centers an effective place to teach search and rescue dogs? These places mostly look the same: a small, artificial search field, often containing some stones, beams, planks, and sometimes other building-waste. In this field are permanent hiding places, mostly complete with cover. The candidates for tests have trained on it, and dogs walk straight to these hiding places. Each dog locates and alerts for these places very well, of course. But when every dog alerts well, then there is no way to make a distinction between dogs that are actually searching well and dogs that have simply learned the location of the hiding spots. That’s why handlers at such training centers often assess unimportant details and, as a last resort, use a stopwatch to time each dog’s performance. Most handlers and trainers recognize that it is bad to search on the same terrain all the time, and they try to correct this by building more hiding places than are necessary. By changing the location of the hiding places, handlers or trainers may think that they can mislead the searching dog. The results say a lot about the capabilities of the dogs, but not much for their handlers.

Figure 7.3 Heavier terrain and more difficult circumstances will engender more excitement in the dog during searches.

Dogs Have a Good Memory After searching more than once, sometimes even after only one search, dogs show that they can find set hiding places without any problem. We once had to give a second demonstration on the same terrain, one week later. Both times, the same handlers and dogs were used. The dogs had some problems the first time around with locating one of the victims, who was hidden in a closed garbage container. All dogs showed very well that they had picked up the odor of the victim, but it took a bit more time to pinpoint the victim’s exact location. This makes sense, because a container designed to keep the stench of the garbage in also keeps the human odor of the victim in. The second time, however, all the dogs walked straight to the different hiding places and also to the garbage container. With this, the dogs showed clearly that they were making good use of their ability to remember. We have observed the same phenomenon many more times while watching the training of search and rescue dog units with a wonderfully equipped training field of their own. The training field often had different rubble objects, but the hiding places were always in the same spots. After one or a few days, most of the dogs knew where they had to search. They walked straight to those places to see if there was someone in them. We learn from this that we constantly have to look for new training fields and debris piles to keep the dogs really searching. We also learn that search and rescue dog examinations held in permanent training fields have absolutely no value. Dogs and handlers trained and certified this way will prove during a mission that they are unable to work out their job because a real mission lacks well-known hiding places. Disaster Villages Disaster villages—artificial, often massive villages built out of concrete for training rescue workers—are not suitable for training search and rescue dogs. The problems with the hiding places are the same as those described for dog training centers; in fact, they’re sometimes worse. The turbulence in such artificial setups caused by the systems of tubes used to build these places is often confusing and is seldom like real rubble. In artificial rubble piles, there is also another problem: because of reinforced structures to prevent collapsing walls and stones falling down, the handler and the dog come to have a confidence and ease they will never have in a real operation. The critical assessment of the status of damaged and collapsed buildings, and the associated judgment of the dangers involved in entering them, can’t be experienced and trained for. This poses a great danger if dogs and handlers trained in artificial disasters then attend a real search mission. Fresh Rubble Anyone who has experienced a search operation after a major earthquake even once will agree that training handlers and search and rescue dogs can’t be based on compromises. Demolition sites and condemned buildings have to be available as training terrain, if only to allow the handler and dog to gain the necessary experience in judging the dangers—an experience that can’t be lacking during a real mission. We know that it is not easy to find demolition sites, and you can occasionally use a rubble breakery or storage area for training—but only occasionally. Dogs training for search and rescue have to be trained regularly, twice a week at least, in the different areas (searching, grid pattern, alert, obedience, dexterity). Handlers should not forget to include evening and night training. Furthermore, dogs must be kept in a good search mood with all sorts of tracking and search performances. Besides training the dog, the handler has to be taught the theoretical background of the work, assessment of dangers, life-saving actions, and so on. It is important that every handler, during training, be fully prepared mentally and physically, and also be tested thoroughly. This is the only way a real selection can take place, which could mean the difference between life and death later during a real operation. Training Essentials During training, everything has to be done to increase the capabilities of the handler and dog team. They should be trained under a variety of exciting search conditions, such as

• Deeper search actions (the helper is hidden deeper) • Longer and not immediately successful search actions • Searching under all sorts of conditions and situations. Conditions such as smoke, stench, noise, and people are overrated. However, a female dog in heat can form a natural obstacle for working males. And believe us, during an actual mission there often are such females. Because of that, females in heat are included in our training scenarios. Searching Without Prey An experienced search and rescue dog and its handler should, unknown to them, occasionally train a search action without a victim in place. The result is that the dog searches without finding—because there is no victim to find. The dog will not be frustrated by this failure, because not having found anyone, it will not expect the full hunting ritual to be carried out. Such a dog doesn’t need to be rewarded, praised, or comforted. The absolutely normal lack of success while hunting is something a wild dog experiences daily. Because the search and rescue dog has inherited this tendency, it won’t view the experience as negative. Through this failure, the urgency to succeed the next time will increase more quickly and the desire to search will be even stronger. Following this chain of logic, which we have tested, handlers come to recognize that they should not offer a replacement victim after a negative search.

Figure 7.4 The result of training should be a search and rescue dog with a strong passion for searching certain areas, such as rubble, woods, or snow.

Case Study: Gas Explosion in the City I am watching the late news when the alarm is called out: “A multi-storied house has collapsed after a gas explosion: we need three dogs.” It is a bit after 11:00 p.m. While I am donning my jumpsuit I remember our last mission. We have just come back and I am still unpacking. And now I am standing in my jumpsuit again, ready to go on the next operation. I fill the can with fresh water for the dogs and we are on our way. I look at my watch: five minutes have gone by since the alarm; I am satisfied. With the phased traffic lights, I am lucky in the always busy traffic of the city. I quickly pick up the last dog handler with his dog. Now we have three dogs in the car; our operational crew is complete. Other handlers are already on standby. The traffic becomes quieter, and we can take the shortest way. Through a street with one-way traffic, and then we see the fire department vehicles. Calmly the handlers and their dogs leave the car; I am satisfied and have a quiet feeling. A nervous dog handler does not achieve good things. I walk through the outlet, an open part in a row of houses, and then I see in the full light of the floodlights what has happened. The back wing of a house has collapsed. Six floors lie in a pile in front of me. Little concrete, but a lot of bricks, planks, and beams. I try to form a picture for myself. Where might survivors be found? It doesn’t look very good. Planks and beams lie on a slant, and only a ten-foot (3 m) piece of a wall from the courtyard is still standing. The fire department commander tells me all the facts known and asks us to search from the courtyard.

Figure 7.5 After arrival, I first find a quiet place for my dog to lie down.

My two colleagues start the work with their dogs, each on one side of the debris. How many victims to expect is, as always, a big question mark. A woman on the first floor must have been at home for sure, but there are five floors on top of her: about thirty feet (7 m) of fine rubble closely pressed together. God help her! The fire department is working on the installation of security measures in the stairwell. A light odor of gas is hanging over the site of the accident, but the fire department commander has ensured gas and electricity are disconnected. I want more information about the possible number of missing people. A crying woman is hardly able to speak: “My grandparents were upstairs on the fourth floor.” Upstairs? The fourth floor is lying in front of me. I give this less-than-precise information to the fire department commander: “Fourth floor, two elderly people were probably in the house at the moment of the explosion.” Blinded by the floodlights of the newly arrived television team, I head in the direction of the rubble pile. My handlers come back with their dogs from the rubble. They have completed the first hasty search. One of them tells me he got an alert of a dead victim and asks me to search that area again. I tell my dog he can start searching. He walks on the rubble cone and I follow him, mostly on my hands and feet. I see him again; he stands still with a half high nose, he is smelling the surrounding area. He goes to the right and shows interest at a place at the edge of the rubble above. He paws some rubble away, smells once more, looks at me and lightly waves his tail. Then he scratches again a few times without confidence and stays in place with his ears laid back, staring at the rubble. Then he gives me his death alert, sitting down and putting his nose deep in the rubble. Hours later I know why he was not totally sure. Between him and the dead body lay about nineteen feet (6 m) of fine, tightly packed rubble. One of my colleagues, who was watching me and the dog, nods affirmatively that his dog also indicated there. My colleague tells the commander of the fire department where he can start digging. I reward my dog and ask him to search further. He goes to the left and comes to a piece of the house that is still standing. High above, the washbasins and radiators are hanging loose on the wall. Along the wall some beams come out of the rubble. The dog shows interest, goes left along the woodpile, and smells there for a longer time. Then he gives his death alert and carefully pulls a wet rug out of the wood. What does he want to say to me? The members of the fire department ask what is happening. “I’m not totally sure,” I hear myself say, “let a second dog search the same area.” That dog sniffs in a clear, audible, intensive fashion in the same place, scratches some rubble away carefully, and lies there softly crying with his nose between the planks. He has also smelled a dead body! From experience I know that a dog’s alert at a dead person is totally different than at a living person. We compare the results of both dogs and determine that both showed a strong interest left of the floor planks near the center of the debris cone. The fire department commander orders digging near the floor planks. I explain to him how such planks can redirect the odor. Because of that, the right location could be situated more to the center.

Figure 7.6 I follow my dog across the rubble, letting him take the lead.

Figure 7.7 The dog sniffs in a clear, audible, intensive fashion on the same place. He scratches some rubble away carefully and lies there, softly crying with his nose between the planks. He smells a dead body!

I tell him about the direction-showing alerts of our dogs, and how we bring them back to the hole being dug in the rubble to show the right direction to dig for the victim. The debris cone to the right of the spot where the dogs alerted has to be worked very carefully, because of the danger of collapsing the adjacent properties. They can’t use machines to dig, and members of the fire department are working hard to move the high pile of rubble away with their hands. It will take hours before they reach the dead body. The dogs lie down now to rest between jerry cans with water and stretchers in the piles of dust in the corridor to the courtyard. Around them are perspiring and panting members of the fire department, sobbing women, busy journalists, and police. Lit by the fierce floodlights of the television crews, the dogs sleep. But time and again we bring them back on the rubble to do their direction-showing work. They know how to conserve their energy, because every time they are back on their place, they roll up and sleep again. It is after midnight when the dogs in the tunnel dug by workers don’t alert further in the debris cone, but clearly want to go deeper. After taking away more than three feet (1 m) of closely packed rubble, we see the sad result: both missing people from the fourth floor. The commander makes sure that there is only one still missing: a seventy-five-year-old woman on the first floor, who was at home at the moment of the explosion. We can spare the dogs a bit; the rubble of five floors has to be cleared by hand first. We go into the second back wing of the building and lay the dogs down in a cabinet-maker’s shop. Later in the night we feel a shock and see some cracks in the floor; the staircase hall is sloping a bit more. The salvage stops immediately, and a firefighter places an instrument with a piece of glass in a corner and waits. If the glass breaks, we’ll know that the walls are sliding. The glass doesn’t break, so after half an hour we can work further. By the alerts of our dogs, we expect to find the last victim along the wall against the neighboring property. The work becomes progressively heavier and more dangerous; the staircase is almost coming down. Dawn is already coming when the fire department commander asks for the dogs again. I search first and my dog walks directly to the right very quickly. He indicates between the surface beams. The second dog does the same. There is nothing left for it but to remove the cramped surface beams and dig further there. In between, the rubble gradually lessens. I become nervous. It looks like all dogs were indicating wrong, giving a false alert. A tired member of the fire department becomes impatient and complains. Then the commander of the fire department surprises me. He believes the dogs and encourages his people to dig further. Suddenly we discover a piece of furniture covered with cloth. Part of a bed! Quickly we set up a dog, and his alert is very clear. Almost at the same time, a member of the fire department calls: “I see a foot, the dog has located!” I take off my dust mask. Hours of long, hard work are behind us. It is Sunday. If I turn my back on the rubble, the new day looks so nice it appears nothing has happened.

Wilderness Search

The search for missing people in large wooded areas and other difficult terrain can be done by an individual dog and handler but also with more handlers and their dogs on a search line. In this chapter we first describe search tactics and then discuss types of alert and ranging. Search Methods For the wilderness search, also called an area search, there are four different methods of searching: • Searching along a road • Corridor searching • Sector searching • Searching a slope or mountain Searching Along a Road Searching along a road is a quick search method that can be used when we have information on the possible route the missing person took. With this method, two handlers walk, one on each side of the road, directing their dogs to loop only to one side of the road. The dog does not cross in front of the handler to the other side but instead stays on one side to search from the edge of the road in loops. How deep the dog is sent into the woods depends on the dog’s ability, the density of the area, and the direction of the wind. This search method can also be used by one handler with a dog. The dog searches first one side of the road and then the other side on its way back. It is advisable under these circumstances to take along an assistant without a dog. No one should go alone on a mission. With this search tactic we have to teach the dog to range the area only to the left as well as only to the right side of the handler, as appropriate.

Figure 8.1 Road search. When two handlers search along a road, one directs a dog to search to the left side of the road and the other to the right.

Corridor Searching With corridor searching, more handlers and dogs walk in a straight line through the area at a large distance from each other (about 55 yd. or 50 m). The distance between the handlers depends on the accessibility of the terrain and the ability of the dogs. They should be farther apart in open terrain and closer together in thick shrubs. The line is preferably arranged so that dogs with lower ability, which can search only smaller areas, work beside more experienced or higher-ability dogs, which can search larger areas. With this search method, the dog crosses in front of its handler to search both the left and the right side areas between the handlers. For the corridor search to function best, there should be at least three and at most five or six handlers. If more handlers and dogs are available, then they can choose to search by sector or form a second corridor search line, which will be placed behind the first one. With this latter approach, the handlers of the second search line should be staggered behind those in the first search line (like rows of seats in a theater). This method is useful when an area has to be searched intensively. The handlers of the first search line can walk a wider distance from one another because the area between them will be searched once more by the second search line. So the dogs don’t disturb each other, the distance between the first and the second search line has to be at least one hundred yards (100 m). The second search line works independently of the first search line. After a search line has been drawn up at the beginning of the area and the command to search has been given, the handlers send their dogs looping in a systematic grid pattern from left to right throughout the area. It is of great importance that every command to stop or continue searching be passed on from every handler to the adjacent colleagues. Working in a corridor search requires much discipline and attentiveness to make the search mission a success.

At one edge of the search line walks a handler or helper who can orient well in the terrain (using a compass or GPS navigation device) and who keeps an eye on the borders of the search area. The whole search line must be directed by this person. In Figure 8.2, this person would eventually replace the marking flags.

When the line makes a side movement (for instance, when the line is searching its way back along a bordering area) it is important that the person standing on the border on the side the line is moving toward keeps standing there. That person knows the border of the area the line has just completed searching.

Figure 8.2 Corridor search. In a corridor search, the handlers walk parallel to each other and their dogs range back and forth to search to both sides of their handlers.

Leadership Is Essential During a course for beginners and advanced search and rescue dog teams, many handlers got irritated with the way the operational leader—the middle person in the line—was giving commands during a night exercise in which they had to search a large area of forest. This person was giving commands loudly, was not willing to discuss the search pattern to be followed, and was leading the whole corridor at a high tempo, which was not easy because of the darkness and the terrain. For the beginners, it was too difficult to follow this experienced search and rescue dog handler, who had already completed many wilderness searches. The beginners were not satisfied with the way he did things, and after everyone returned to the hotel, there was a great deal of discussion about what happened, although the exercise worked out very well. Some beginning handlers, who doubted the success of the exercise, arranged for a night exercise that they would command the following evening, where they could work it out their own way. It was a disastrous exercise because of the endless discussions about the search pattern to follow, the division of the terrain, and which dogs should search where, all of which took an enormous amount of time. Many handlers were confused about what was to happen next. Each time a part of the line stood still, another part continued. The line had to be constantly reconnected and regrouped. There is much to be learned from this story. The leader should be aware of the experience of the handlers in the group and adjust the pace and directions to ensure everyone can contribute effectively. On the other hand, handlers in the search group should not interrupt the search to discuss search patterns. During the search, everyone must follow the leader’s orders. Especially with corridor searching, discipline is of the utmost importance, because you are working in bigger groups and always walking some distance from one another. If the line falls apart, the whole area has to be searched again or something may be missed. There is time in the debriefing to ask questions and discuss problems.

Figure 8.3 It is important to discuss every exercise thoroughly, but not during an operation, when efficiency and speed are critical.

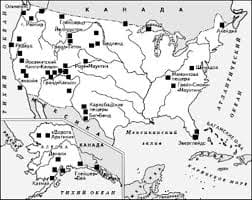

Sector Searching The total search area can also be divided into several sectors, depending on how many handlers and dogs are available. These sectors, the borders of which have to be clearly marked by roads, ditches, or geographic coordinates in latitude and longitude, will be searched by two or three handlers and their dogs (using a corridor search). The advantage of working this way is that smaller, more numerous units can work faster. The disadvantage is that the handlers have to orient themselves very well in the terrain so that no areas are missed. That’s why this search method has to be coordinated centrally, with all groups equipped with a radio and GPS for control.   Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|