|

|

BEARING THE WEIGHT OF THE MARKET?Most people in the advanced economies seem willing to accept, most of the time, that economic integration through international flows of trade and finance is a good thing. They acknowledge, for instance, that foreign investment can help poor economies to modernise, and that international competition helps to raise productivity and, at least in the aggregate, incomes as well. Yet people also recognise the costs, such as unemployment or lower wages, that integration may force on particular groups at certain times. When weighing these costs of globalisation against the benefits, economists typically point to the role of government. Through taxes and public spending, they say, societies can use some of the extra income created by globalisation to cushion the losers. In principle, governments could go further, ensuring that everybody ended up better off. Which is very reassuring - unless it turns out that integration itself reduces the freedom of governments to act. The view that globalisation makes it harder for governments to govern has come to be widely accepted. The basic idea is simple enough. Globalisation adds to the reach and power of the market: now even governments, not just firms and people, must bow down before the new master of worldwide competition. A government might want to prohibit dangerous or undesirable working practices, for instance. But if it did, the affected industries might move abroad or shut down, because the new regulation could put domestic firms at a disadvantage in competition with foreign producers. Or suppose the government wants to raise taxes and spending. However popular more public spending may be with voters, the market might well forbid it. In the new global economy, people and firms can flee to other tax jurisdictions rather than paying an onerous tax. Governments do not even have their former freedom to design their own social policies, the argument continues. The financial markets now sit as judge; if they deem that a new national health-care scheme or a massive education reform will prove too costly, they will punish the country with higher interest rates or a collapsing currency. In this way global market forces not only rule out the kind of compensation to losers that would make globalisation easier to live with, they also seem to challenge democracy itself. If this thinking were correct, there would be good reason to oppose further globalisation, or to regret that the process has gone as far as it has. But it is not correct. In part it is muddled and in part it is simply wrong. New thinking Politicians in rich and poor countries alike, regardless of whether they were of “the left” or “the right”, began calling for lower taxes and public spending, for lighter regulation of industry, for privatisation of state-owned enterprises, and in general for their economies to be given greater “flexibility”. In other words, governments have freely chosen to give market forces more sway, in the hope that this will raise living standards. It is odd therefore to say that the global economy has seized power from the state - and it is plain wrong to say that democratic rights have been trampled on. Many would argue, however, that things are not so simple. Having started to liberalise their economies, governments were left with less power than they had expected. And having surrendered more control than they meant to, politicians found they could not go back. As a result, according to this view, globalisation is running out of control. Governments themselves have done a lot to foster this idea. Nowadays no statement on economic policy is complete, it seems, without a declaration of impotence which says, in effect, “Our plans reflect not what we would like to do, but what the global market requires us to do.” Advancing technology adds to the sense of helplessness. Things that governments could once forbid or restrict -foreign borrowing; imports of computer software; pornography; political ideas - are now far harder to control because modern communications have eroded the boundaries between nations. It is true that when technology and liberalisation come together, governments can be taken by surprise. Anomalies appear, sometimes requiring further deregulation, at other times requiring new forms of regulation that previously mattered little. It is also true that governments have sometimes done the right things in the wrong order; liberalising cross-border flows of capital without updating regulation of the banking industry, for example, is one of the factors behind the recent series of financial crises in Asia. Like Topsy The best and simplest measure of a government’s involvement in the economy is public spending. In rich industrial countries this has followed a persistently upward trend since the latter part of the 19th century. True, many governments have tried hard to cut their outlays and their budget deficits of late. By and large, however, they have succeeded only in slowing, not reversing, the rate of growth of spending. Where budget deficits have been reduced, this has been done more by raising taxes than by curbing expenditure. Over the long term, a government’s ability to spend is limited by its ability to raise taxes. In the past 20 years, better international communications and freer movement of capital should have made it easier for taxpayers to avoid high-tax jurisdictions, putting downward pressure on public spending. Why does this appear not to have happened in a significant way? The answer is partly that taxpayers remain less mobile than one might think. Financial capital, to be sure, now moves instantly from country to country. But once capital has been turned into physical assets such as buildings or equipment, moving it is costly. Governments may grant tax preferences to attract new capital to their countries, but they can continue to tax the profits from physical capital that is already in place. Labour, in any case, remains far less mobile than capital -rooted by ties of family, culture and language. In recent years, therefore, many governments have reduced their rates of company taxation (as well as granting special concessions for new investment), and have shifted the burden on to people instead. Taxes on wages and salaries have risen. This has more than made up for the fall in revenues due to lower company taxes. Extremely high rates of personal taxation in many countries, notably in Europe, confirm that people cannot readily escape the clutches of high-spending governments. It is true that competition among governments has changed the structure of personal taxes in many countries, as the extremely high rates paid by the highest-income taxpayers have been cut. So far, however, this has failed to reduce the overall tax burden. Free to borrow So much for taxes and spending. What about public borrowing and monetary policy? It is often argued that today’s global market for capital applies a particularly severe discipline in these areas. Again, this is misleading. In the first instance, greater mobility of capital gives governments more freedom of manoeuvre in fiscal policy, not less. By borrowing from abroad, they are able to let their spending exceed their revenues by more and for longer than would be possible if their economies were closed to international finance. Of course, if they abuse this freedom, capital markets will turn against them, and raise the offenders’ cost of borrowing. But this is only like saying that people who run up too big a bank overdraft will be offered poor terms for further loans. The fact remains that an overdraft facility increases financial freedom, it does not reduce it. Admittedly, living with financial freedom can be more complicated than living without it. In particular, the extreme mobility of modem financial capital makes monetary policy more difficult to conduct. For instance, it has become difficult for governments to peg their exchange rates indefinitely in the face of adverse circumstances. The risk of “contagion”, when a crisis in one country leads the market to change its view of prospects in others, is a further complication, as recent events in Asia have emphasised. Nonetheless it remains entirely possible for a government to use monetary policy to steer the domestic economy, provided that it is willing to let its currency float. Today’s global capital market only rules out sooner what has always been impossible in the longer term - namely, treating interest rates and the value of the currency as entirely separate instruments matters. Globalisation has not altered the basic limits: monetary policy can be used to regulate the domestic economy or to regulate the exchange rate, but it cannot successfully accomplish both goals at once. Finally, what of the argument that the new global economy makes it impossible for governments to mandate social protection, such as minimum-wage laws, rules on working hours, health-and-safety standards in the workplace, and so forth. According to this popular view, if governments grant such protection, they will make their firms uncompetitive and put workers on the dole. Globalisation is thus blamed for a “race to the bottom” in economic regulation. There is no reason why this should be true. Certainly, social protection does carry economic costs, reducing the amount of output that can be squeezed from any given amount of capital, labour and other resources. This is not to say that social protection is wrong. Citizens may well decide the cost is worth paying. But the cost must be borne. The only question is how. In an economy closed to flows of trade and finance, the cost will take the form of lower incomes. In an open economy, the same must ultimately be true. This basic logic is the same whether the economy is closed, partially open or globalised. The only difference is that open economies with floating currencies may experience that fall in incomes through currency depreciation - and thus higher prices for consumer goods-while a closed economy will suffer a decline in wages as expressed in the local currency. The important thing to remember about social-protection rules is simply that, in economics, you rarely get something for nothing. That is the bad news. The good news is that social-protection rules are as feasible, and in the end no more costly, in a globalised economy than they are in a closed economy. Much the same goes for financial regulation, public spending and macroeconomic policy. Governments, always eager to deflect political pressure, may prefer to justify unpopular decisions by pretending that their hands are tied. In truth, despite all the changes in global markets, they have about as much, or as little, control of their economies as they ever had. VOCABULARY:

TRANSLATION NOTES: However popular more public spending may be with voters, the market might well forbid it – Каким бы популярным рост государственных расходов ни был… (См. часть Ш, раздел 3, §12) При таком варианте перевода нам придётся пожертвовать глаголом “may” в функции предположения. Рекомендуется перевести данное предложение следующим образом: Несмотря на то, что рост государственных расходов, возможно, и вызовет поддержку среди населения (избирателей), рынок вполне может воспрепятствовать этому (воспротивиться).

Having started to liberalise their economies, governments were left with less power than they had expected” – После того, как правительства начали либерализовывать свою национальную экономику, оказалось, что у них осталось меньше властных полномочий, чем они предполагали. Здесь предпочтительнее вместо причастной конструкции использовать придаточное предложение времени.

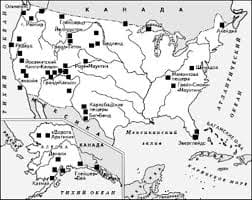

Text B   Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|