|

|

Showing People the right way of life

He showed right path to many people who are in bad habits like drunkards, the wicked, robbers, thieves, and so on saving them from the evil way of living. He showed them the light of Pushti-Marga which led them to right path.36 Vallabhacharya as A Renovator of Social Life

The achievements of Vallabhacharya in social life in his time should be estimated in the light of the above words of Dr. Radhakrishnan. He made the content of the Hindu Dharma, relevant to his times. Besides being a great Philosopher, a great religious teacher and a mystic, Vallabhacharya was also a great social thinker. Although he spent most of his time in visiting various parts of the country and preaching religious guru, he was not isolated from the social life of the time. He came in contact with men of all orders in the society, observed and studied their ways of life and was convinced that the old Vedic form of the Hindu Religion had little chance of revival in that age. The ceremonies, performed by the priestly class and the followers of the Hindu faith, were practiced only mechanically. Under the name of Dharma wrong things were perpetrated. The social body of the Hindu society in general, was showing signs of feebleness, it was losing health fast, and there was little hope of its recovery from degeneration and decay. Vallabhacharya felt that Hinduism could not be preserved and rescued unless some strong timely doses in the form of reoriented religions.and social concepts were injected into it. He saw that the malady had gone deep into the bowels of the social body. He therefore, suggested certain reforms. He thought that the Dharma required reorientation. The Dharma taught by the Smritis was losing its grip on popular mind. It was misunderstood, as signifying performance of sacrifices, practicing penance, observing rules of purity, visiting holy places, exercising mental discipline, devoting life to knowledge and worship but the fact that it is inclusive of all these and yet much more was missed from the popular mind. What is called Dharma is an internal urge and inclination of the mind expressed in the form of one's duty to one's self, to society, to mankind and to God. He believes that if the Dharma does not improve the relations between men and men, and if it does not point the way to the union with God, it is no Dharma. The true nature of Dharma makes a man fearless and prevents him from doing injustice to others by harming their interests, or disturbing social solidarity and creating tensions causing disruption of the social orders. It makes him discri-minate between what is socially good and bad. It makes him prefer social good to individual good. It also makes him free from. 'I-ness' and 'mine—ness'. It implies the purity of heart and not of the body only. It is not self-love but is universal type of love, which triumphs over distinctions due to caste, creed and color. Vallabhacharya was a spiritual social reformer. He conserved the spiritual values, by suggesting new reforms in outer social practices. It was his belief that social reforms without religious control was good for nothing. His social philosophy is based upon the sense of Dharma-as universal Dharma i.e. Love to all as God's creatures. The marks of Dharma are fearlessness, purity of heart, content-ment of mind, sincerity, compassion to all creatures, and service of mankind. All these are good. If Dharma is not related to God, it has ho value. The Heart of one devoted to Dharma, overflows with love for all. It delights in doing well to all, and helping them in their needs and difficulties, according to one's ability. It treats all creatures equally as God's beings. It loves truth and justice, and desists from harm or violence. It esta-blishes harmony everywhere and realises oneness of God in all beings. It, is a Dharma of the heart and not of the intellect. Vallabhacharya applied his mind to it for a long time in formulating his view on the real nature of Dharma, and taught it to the people as a panacea of all the ills-social, religious political or spiritual. Before prescribing this, he made a correct diagnosis of the disease of the social body. The Hindu Society not only survived the Islamic attacks but had a long lease of life under the impact of his social philosophy. This is the greatest service by Vallabhacharya to the Hindu Society. He was a reformer, who reformed the society without any disturbance in social life. According to him, sudden change in the existing order of the society, was a blow to it. He did not root out the tree, but removed the cancerous part from it. Institution of Class System

He believes that a man's class depends upon his qualities and not upon his birth. The caste is not hereditary. If a Brahman possesses the qualities required of his class, he should be regarded as a Brahmana, but if he does not possess those qualities, even if he is born as a Brah-man, he should not be considered as a Brahmana. He is unfit as a Brahmana, but a Brahmana only in name. This rule applies to all classes. A man may have been born in any class but if he lacks the qualities of that class, he should not be recognized as a genuine member of that class. So, birth should not be considered as a crite-rion for ascertaining a class or a caste. The orthodox people, how-ever, believe birth alone as a criterion for determining the caste of a person. In the days of Vallabhacharya, the old class system de-generated into innumerable sub-divisions of castes within castes, and only birth, and not the qualities, became a chief rule of social order. Under the caste system inter-marrying, even among tile members of the divisions of the same caste were forbidden. Vallabhacharya saw the evils of the caste, and wished to re-form it, but he did not want to aim a blow at the old class system, because that would be anti-Vedic and demolishing a very ancient institution, which gave shelter to people for thousands of years and was very useful, in the preservation, harmony, and integration of the social order. His attitude to caste was that of renovation and not of demolition. He looked upon that problem, philosophically and religiously. The economic and cultural considerations were subsumed under these two. The qualities which form the very basis of these classdivisions are innate in them and their functions are external expressions. The qualities are the mental equipment of the class and the functions its physical expressions. The deciding factors for the class according to the Scriptures are the qualities of knowledge— The Hindu Muslim Unity

Vallabhacharya kept himself away from politics, but be-lieved in Hindu-Muslim unity through culture and religion. Just as he has thrown open the portals of his faith to the Shudras and the untouchables, so also he threw them open to the Muslims, if they were very ardent about it. Under his influence, the Muslim rulers relaxed their attempts of proselytising the Hindus to the Muslim faith. His son Vitthalesha followed his father's liberal policy in this matter. He was a very practical Acharya. He thought that the solidarity of the Hindu commu-nity could be maintained by that liberal policy. Emperor Akbara honoured him for his catholicity and fellow-feeling. He often visited him to have his Darshana and listen to his sermons. He conferred upon him the honorific title of Goswami and also granted him and his descendents some privileges, viz. the graz-ing of his cattle, non-molestation of his cows, protection of his pro-perty and exemption from taxes by special firmans. Sometimes some legal cases of complicated matters between the Hindus ver-sus the Muslims were referred to his arbitration by the emperor. His son Jahangira following the footsteps of his father showed his sympathetic attitude towards Vallabhacharya's faith. The records of this faith are full of many notable examples of the Muslim devotees. Some of them may be referred to here. Alikhana Pathan, who was in charge of the land of Vraja as an administrator, during the regime of Sikandarshah Lody, the emperor of Delhi, was initiated in the path of Pushti. He was a disciple of Vithaleshji. He used to offer divine service to the image of Thakurji Madan Mohanji—a form of Krishna. He always attended Vallabhacharya's discourses of the Bhagavata. He had so much love for Vraja—where Krishna spent early days of his life, that he had issued strict orders, banning the plucking off leaves or cutting of the branches of the trees in that land. He made his permanent residence in Vraja. It is said, that he was so much fascinated with the love for Krishna that, he used to wander like a-mad man in-search of Krishna. His daughter Khan Jadi, also was devoted to the service of Lord Krishna. She was an ardent lover of his faith. She remained unmarried and spent her life in experiencing pangs of separation from Krishna. It is said that Krishna, pleased by her devotion, blessed her with His reve-lation to her. Tansena, known as the King of Musicians at the court of the Emperor Akbara, accepted Vitthaleshaji-the son of Val-labhacharya, as his preceptor. He has composed some songs in praise of Krishna's lila. One Muslim lady Kunjari, who was very thirsty, and was on the verge of death was saved by Vitthalesha, by giving her water reserved for Divine service, embraced his faith arid set an example of an ideal devotee. Bagikhana though a muslim accepted the discipleship of Vitthalesji. Rasakhana was a great favorite of Vitthaleshji. He was a great devotee of Krishna. Like; Suradas, a great poet of Hindi, lie himself wrote many songs describing the litas of Krishna. Rasakhana‘s ‗Kirtanas‘ are sung, even now, before the image of God in the holy shrines of the Pushti Marga. Many Hindus went to him for receivings instructions in religious matters. There is a story of a Pathan boy, recorded in 'Two hundred and fifty two Vaishnava followers of Vitthalesha' that, when he accepted the Vaishnava faith, his parents were opposed to it. They requested the Muslim ruler of that place to dissuade him from changing his faith. The ruler used all possible methods-of coercion to give up his new faith, but he was firm like a rock and did not budge even an inch from his resolve of accepting the faith of the Pushti Marga, so, the ruler had to allow him his wish. There are many such examples of the Muslims, having em-braced the faith of Vallabhacharya. If any deserving Muslim expressed his willingness to accept his faith, Vallabhacharya did not object to it on the ground of his being Muslim. He would not recommend interdining and intermarrying between the Hindus and the Muslims but he would not shut the doors of religion against them as they were equally qualified for a religions life, according to the Hindu scriptures. From these examples we can say that Vallabhacharya and his son Vitthalesa made a large contribution to the Hindu-Muslim Unity, which is unparallelled in history during the Muslim regime. It is a unique achievement and triumph of his religious policy even in the political field. Vallabhacharya had a sympathetic regard, even for the so called untouchables. He admitted them to the path of devo-tion. In his faith, there are some notable devotees, whose exam-ples are recorded in the books. According to the stories of Eighty four Vaishnavas and The stories of Two hundred and fifty two Vaisnavas, one Patho Gujari was a favourite of Vitthaleshji. It is said that one Chauda, a follower of Vitthaleshji, who belonged to the untouchable class, was specially favoured by Vithaleshji on account of his extreme yearning for the Darshana of Shrinathji. One Chahuda—a follower of Vitthaleshji defeated learned scholars, in a controversy concerning religious matters. Vallabhacharya and Vithaleshji were very liberal to the untouchables. They did not deny their right to religious life. They had the same rights for devotional life, as the other Hindu castes, provided they were clean in their food and dress, and were really sincere in their desire for being admitted to the path of devotion. Though the Hindu society was reluctant to remove the social restrictions against them, Val-labhacharya, without interferring and disturbing the status quo made them fit for religious life, preserving of course the spirit of the Smritis and other scriptures. The way of acquiring fitness is cleanliness of body and food, purity of heart by virtuous conduct, etc. and the desire for a devotional life. If they possess these qualities, they are fit to contact holy men, attend religious sermons, parti-cipate in singing divine songs, and to have the Darshanas of God's image in the shrine from a distance. Attitude towards Women

Towards women in general Vallabhacharya's attitude was highly advanced in consonance with the religious spirit of the scriptures. He regards them as equals of men. He accords them the same position, which was held by them in the Vedic period when, they enjoyed rights equal to those of men for a religious life. Husband and wife both took part in the sacrifices. Wives offered prayers with their husbands. They were not precluded from the study of the Vedas. The girls were allowed to put on the sacred thread. Some women like Maitreyi and Gargi could participate in philosophical discussions. Some women like Vac are famous as composers of the Vedic hymns. There were two types of women, Brahma-Vadini, who remained.unmarried throughout life and devoted their time to the learning of Brahma-Vidya, and others who were Sadyovahini, who married. This position of women began to deteriorate from the time of the Mahabharata and, in subsequent ages in consequence de-generation of women reached the climax. During the age of Val-labhacharya the position of women, under the impact of Mus-lim civilisation, was the lowest. They were very backward social-ly, economically, and culturally. Vallabhacharya endeavoured to ameliorate their position in the religious way. During the Smriti period, women suffered from various disabilities, which included, religious disability banning them from the pursuit of the Vedic study. In this respect they were put on par with the Shudras, but the Gita made the ban futile by admitting women to the path of devotion (B.G. X-32). Vallabhacharya, does not make any distinction between men and wome|, because they are identical iii having souls. According to him, the devotees having the body of a man or of a woman, but possessed of the qualities like love, steadfastness, Selfabnega-tion, penance etc., are better qualified for God's love than mere males or females, devoid of these qualities. So merely having a woman's body does not qualify her for devotional life, but the above qualities. The Gopis who possessed these qualities are ideal "women, fit for God's grace. He pays them highest tribute of eulogy by calling them-the Gurus in the-path of devotion. In the Karika portion of his Subodhini, Vallabhacharya says that women alone are fit for the bliss of devotion and their husbands can acquire fitness through their wives (Bhg. X-29). In the Subo-dhini on the Venu Gita, (Bhg. X-185) he says that the love of the type of a woman for her lover is the real-love in the Pushti Marga for God-realisation. It is an ideal love, because it is free from vul-garity of sexuality and capable of sacrifice, suffering and facing all kinds of difficulties, trials and tribulations (Bhg.S.3-14.K.-13) In his opinion a woman is a better teacher even than an Acharya, because knowledge or instruction received from her has an im-mediate effect on the recipient. In his sympathy for women, he says that if a tear falls from the eyes of a woman on account of her molestation or persecution by men, the earth will lose its fertility. Vallabhacharya is always full of praise for good women, though he condemns wicked, women. They are a bane, a cause of men's downfall and degradation. Hearts of bad women are like those of wolves. (Bhg. X-33-40) He supports love marriage as an ideal marriage and ignores-even a caste-barrier, if it interferes with it. One Ramdasa, a disciple of Vallabhacharya who ill- treated his wife and abandoned her, was advised by him to re-concile with his wife. He accepted his advice and lived with his wife a happy life. Rana Vyasa and Jagannatha Joshi, both the disciples of Vallabhacharya saved one Rajput lady from death by burning on a funeral pyre as a Sati after her husband's death. The lady was advised by them to seek guidance of Vallabha-charya, which she did and turned a new leaf in her life. He sympathised even with prostitutes, by admitting them to the path of devotion (The story No. 9 in 'Eighty four Vaishnavas)'. One Krishnadasa, one of the eight poet disciples of Vallabhacharya's faith, having been captivated by melodious music of one prosti-tute made friendship with her and presented her to Lord Shrinathji, before whom, she used to sing songs of God's lils. The marriage of a son of one Bania with the daughter of a minister, who was Rajput by birth, was approved by Vitthaleshji when he knew that they were sincere in their love. He and his son Vitthalesji did not openly encourage inter caste marriages, but if among the Vaishnavas, a youth and a girl of different castes really loved each other and married, they did not object to it: There are examples of women belonging to the Shudra and aboriginal classes who were accepted in this faith for devotional life. Several of them experienced God's love. He exhorted his disciples to get themselves married, so that as husband and wife they both would devote themselves to the joint service of God. The object of a householder's life, according to Vallabhacharya, is service of God and not enjoyment of sexual pleasures. The married life is to be enjoyed with a view to getting children, who can be helpful in the service of God. Husband and wife are advised to love each other, live in peace and do service of God together. A Vaishnava must not shun his wife, unless she proves a hindrance to him in the service of God. He is even bound to maintain her even then. Attitude to the Vedas

The Vedas are the earliest sacred works of the Hindu, trustworthy for philosophical and religious knowledge. They are four—Rig, Sama, Yajur and Atharva. The-word 'Veda' means knowledge. These 'Vedas' are so called, because, they are reposito-ries of knowledge. They give knowledge about two subjects—(a) sacrifice, and (b) Supreme Reality. The portion of the 'Veda' which deals with Sacrifice is called 'Purva Kanda' and the portion dealing with knowledge is called 'Uttarkanda'. Sacrifice is independently treated in the works called 'Brahmans' and know-ledge in the 'Aranyakas' and the Upanishadas. Shamkara accepts only the Uttarkanda as an authority and Jaimini only the Purvakanda. Ramanuja, and Vallabhacharya accept both, as of equal importance. According to him, there is no opposition between these two parts, because sacrifice and know-ledge are the two powers of God, each of which is given in-dependent treatment in each Kanda. Although Shamkara accepts the authority of the Upanishadas, yet, when he is perplexed about the nature of Brahman which is described both as Indeterminate and determinate, he prefers the former Brahman to the latter, and rejects the Shritis supporting determinate rahman. So according to Shamkara all Shrutis are not equally valuable. In such a case, he will not resort to the Shrutis but to reason. He says that, if there is a conflict between the Shrutis and reason the latter must be given preference to the former. Thus, Sham-kara does not accept the entire Vedas consisting of the Purva Kanda and the Uttara Kanda as authoritative. Again he does not accept all the Shritis from the Uttar-Kanda as authoritative. Val-labhacharya, on the other hand, accepts the entire Vedas—con-sisting of both the parts as authoritative and of equal value. As for the Shritis, all are trustworthy, without any exception. He is against making any distinction in the body of the Vedas. The Gita is the speech of God, but the Vedas are the vital breath of God. It is a crime to dissect the body of the Vedas into limbs or parts and recognize some parts as genuine and reject others. Purva Kanda deals with God's power of work and the Uttara Kanda, on God's power of knowledge; both are integral and necessary, each co-operating with the other, for the organisation, preservation and maintenance of the body, in the form of the whole Vedas. Vallabhacharya has noted this point in his 'Anu Bhasya' com-mentary on the Brahma Sutras (1-1-7). Work and knowledge belong to Dharmin—God, so there is no opposition between the two (B.S. 1-1-3). He says that those who accept only one part of the Vedas neglecting. The other, ought to be ignored. They interpret the Vedas not as they are but as their fancy guides them. It militates against the spirit of the Vedas which are not to be explained arbitrarily. The Vedic truth is cent per cent purified gold. It is not to be undervalued by a mixture of any base metal in the form of extraneous matter. Any attempt towards distortion or perversion of the Vedic truth by wrong interpretation, deserves downright condemnation (Bha. II-7-37K). Vallabhacharya ac-cepts the Vedas as an exclusive authority. He rejects other Pramanas such as perception, etc. They may be good for know-ledge of worldly objects, but not for the knowledge of God. He holds the Vedas in the highest esteem. He attaches so much impor-tance to the Vedas that he says that everything written in it, even though it may seem to our scientific mind, impossible, incredible or fake, must be believed in, because sometimes, incredible things mentioned in the Vedas, should be accepted as indi-cative.of events in the future. The Vedas are hot only trustworthy for the past, but also for the present and the future. They are not like historical works, written with a view to describing the past happenings, but are the writings which serve as guides to the individuals and they nations, 4n their spiritual development, for all times. They are universal and perennial works, useful to those who serve inspiration and guidance from them, for spiritual development. By the knowledge of the Purva Kanda, one knows the nature of sacrifice which represents the action-form of God and by the knowledge of the Uttara Kanda, the nature of God as knowledge and realises Him. Each part is complimentary to the other. He, who has known the entire Vedas, will understand that the object of the Vedas is to teach the supremacy of devotion as a means of God-realisation. The real sacrifice or work of a devotee is service of God by consecration and the real knowledge, the know-ledge of the Love-form of God and His realisation by His grace. Institution of Sacrifices

It is a very old institution—as old as the Vedas. It is the main subject of the 'Purva Kanda' of the Vedas i.e. the 'Samhitas' and 'Brahmanas'. It is accepted by Jaimini as the main teaching of the Vedas. It was discarded by the Buddhistic school in to and partially by Shamkara, who, however, accepts its utility as a purificatory means of mind which is essential as a preliminary condition to one seeking spiritual development through knowledge. Ramanuja and Vallabhacharya both recognize its utility for a religious life. The Gita has also recognized its worth. But the Gita says that every action of a man is a kind of a sacrifice and it should be done for the propitiation of God. It should be performed as one's religious duty without regard of fruit. The Gita supports the Vedic sacrifices also and asserts that those who enjoy the gifts of God without offering them to Him are sinners. (111-13). It explains the philosophy of the sacrifice by identifying not only the sacrifice but also all its accessories with God (III-15). It enumerates different kinds of the sacrifices, viz. sacrifices to be performed by materials, by self-control, pe-nance, Yoga, austere vows, wisdom, study of sacred texts etc. (IV.26-30), Having thus mentioned different kinds of sacrifices, the Gita observes, that of all kinds of sacrifices, that of knowledge is the best (IV-33). It should be noted here that the Gita teaches the value of a sacrifice to Arjuna who is recognized by Krishna as his devotee. It means that his sacrifice must be of such a kind that it may help him in achieving the knowledge of God. Vallabhacharya classifies sacrifices into three kinds—(1) Those performed for the fulfillment of one's desires, whose goal is attainment of heaven (2) Those performed without desires, but for spiritual, happiness. (3) Those performed solely with a desire of God-realization, for the goal of union with God and en-joyment of His bliss. These three kinds of sacrifices are called by him as Adhibhautika, Adhyatmika and Adhidaivika sacrifices. He, being an Acharya of the Bhakti cult, appreciates only4 the last type. In his faith, he has evolved the Divine service mode, which to him is the Adhidaivika sacrifice. He follows the Gita concept of a sacrifice, but suggests that the highest kind of a sacrifice— the Adhidaivika-is a means of God-realisation. The sacrifices mentioned in the Gita III & IV are all included by Vallabha-charya in the first two divisions given above. The last division, Adhidaivika, is his own discovery, a unique contribution to the teaching of the Gita. He has accepted the sacrifices and divides them into high, higher and highest types, and teaches that those who seek God must practise the highest type in the form of the service of God. Every selfless act of an individual's life, rendered as service to humanity or to God is deemed by him as a sacrificial act. The highest kind of a sacrifice is the service of God. Self-Control (Yoga)

'Yoga' is one mode of spiritual life as recommended by the Svetasvataropanishad. The Gita also teaches it as one of the disciplines for God-realisation which differs in its meaning of the Yoga from that used by Patanjali, the traditional founder of the Yoga system. The Gita uses the word Yoga in the sense of union with God'. Each chapter of the Gita is titled as a particular kind of Yoga, by which the soul can be united with God. Patanjali does not understand it in that sense, but as a spiritual effort to attain perfection through control of body, senses and mind, and through right discrimination between Purusha and Prakriti, Chapters V & VI of tile Gita deal with the Yoga or self-control as a mental discipline. It is defined variously in the Gita as 'proficiency in actions', state of equipoise' and 'freedom from all pain and misery'. Gita's concept of the Yoga: is not negative like that of Patanjali. According to Patanjali, it is supra-conscious concentra-tion in which the meditatior and the object of meditation are completely fused together, without consciousness of the object of meditation (God). Gita's Yoga is the state of union with God in which the individual self enjoys the eternal bliss with Brahman. (VI-28). It is not enough that the senses and mind should be withdrawn from the worldly objects, but that they should be directed to God. They should be always engaged in thinking about God and experiencing God's love. A Yogin, who directs his mind and senses to God and experiences God's love, is the highest Yogi. Vallabhacharya recommends it for union with God, in which a devotee can enjoy bliss of God's love, which is the aim of his life. This love is to be experienced in two states in the state of service time, and in the state of non-service time, when the devotee should engage his mind in thinking of God and experiencing pangs of separation from Him. Vallabha-charya substitutes the word Nirodha as a better word, than the Yoga in place of Patanjali. In Patanjali's method, mind is to be controlled by suppression; but Vallabhacharya's method is the method of sublimation by which the desires of the devotees are not suppressed but they are enjoined in the service of God. Vallabhacharya adumbrates three divisions of Yogas (1) the inferior kind by which one seeks. To possess certain supernormal powers (2) the mediocre kind, by which one seeks liberation (3) the superior kind which is for experiencing God's love only. However he recommends only the last one. In short, he says that the aim of Yoga is not merely mind control but participation in God's bliss, in union with God. It is a positive way in which the mind, though detached from worldly love, is attached to God, seeking God's love. The value of Yoga is recognised, only if it proves to be helpful in the soul's union with God. Tapas-Penance

The old idea of Tap as- ' Penance5 'voluntarily suffering pains5, is not acceptable to Vallabhacharya. Inflicting pain on one's body is not a desirable and good method for God-realisation. Many a time it has produced disastrous effects on one practicing penance and has failed as a method of mind control. If penances are not directed to experience God's love, they are good for nothing. They have, however, their value in experiencing God's love, in the state of the soul's separation from God. It is not suffering, self-inflicted bodily pains or tortures; but rather a mental state of v enduring pangs of love in separation from God. Such penance is highly commended. It is not an independent means, but is one of the ingredients of devotion of the love-type in the Vyasana state. Prayers

Prayers are a chief feature of Christianity, Islam and some other religions. They also constitute one of the features of Hindu-ism, but to Vallabhacharya the idea of prayers for asking boons of worldly kinds from God is not commendable. Prayers are good for the purification of heart, but should not be resorted to, for asking favours from God, such as securing health, wealth, chil-dren, power, victory, fame etc. That is not the proper use of prayers. By asking for these, through prayers, the devotee betrays. His trust in God. Does not God know his wants? Why should he, then, pray for these things? Again by asking for them, he may get less than what God might have otherwise blessed on him. He must know that his life is strictly ordained by the Will of God which is always for the universal as well as his individual good. If one suffers from any difficulties, he should think that God has sent them, for his spiritual development. ‗Sufferings are sometimes ordeals for testing the true love for God. One does not know what is behind God's will. It is the duty especially of a devotee, to sub-mit himself humbly to God's will and do his duty cheerfully and fearlessly with faith in God, and God is sure to protect him. Ask-ing for worldly things is not true devotion. A devotee of God seeks only the love of God, so his devotion must be free from personal desires. In his Viveka Dhairya Ashraya, Vallabhacharya says, ―What is the good in doubting the purpose of God by offering Prayers? All things, everywhere, belong to Him and all power is His. In 'Nava Ratna Grantha' he admionishes that also devotee should be free from all anxieties. In troubles, he should remember God and think that they are blessings in disguise from God. He, however, does not doubt efficacy of prayers. They have also value but Val-labhacharya says, that they should be resorted to, for securing the love of God. Prayers may be offered for the purification of one's heart, and freedom from the sense of egoism; but no for procure-ment-of worldly gifts from God. Hymns in praise of God called stotras should be sung, instead of prayers. They will tend to increase only faith in God. By praising God, we accept His mastery over us, and become conscious of His guardianship, which gives us strength enough to resist against dangers and difficulties. The Gopi-Gita in the 10th book of the Bhagavata is the best prayer. It is the prayer by the Gopis, who expressed in it their ardent longing for God's revelation (Darshana). The prayer of demon Vrutra, in the 6th book of the Bhagavata, is a wellknown typical example of an ideal prayer. In his prayer, he did not ask for hea-venly happiness, Yogic powers, the position of a creator, libera-tion and sovereignty over the whole world, but asked for God's love only. He says ―Oh, God, I do not ask from you for anything except you. If I have you, I have all. If I do not have you, although I may have all, I have nothing. Like a newly born bird anxiously waiting for the arrival of its mother, or a hungry calf for its mother-cow, or a woman long separated from her husband, I have been anxiously waiting for you. Oh, my love, come to me and bless me‖. The prayer offered by the maidens of Vraja to Katyayani for a boon to have Krishna as their lover, is the highest type of prayers. The prayer of Kunti, the mother of the Pandavas, offered for acknowledgment of obligations of God, and that of Bhishma, expressing repentance, on the point. Of death, are of the second type, and that by Gajendra in the Bhagavata, for rescue from an alligator, is of the lowest order. For a follower of Pushti Marga, the ideal prayer is the grayer by the Gopis or the prayer by the maidens of Vraja to Katyayani. Faith in God

Unshaken faith in God is most essential for seeker of Gopis love. Even the slightest deviation from it, will poison the love for God. Faith should be a guiding principle in a devotee's life. This faith must be in one single form of God, to be singled out by a devotee, out of many forms of God. Love for God must not be directed to many Gods and Godidesses, but should flow continuously and straight to one God, without diversion. God's love is the root of devotional life. As the growth of a tree requires sprink-ling of water, to be poured over the root and not the trunk, branches and leaves etc: so, for the growth of devotion, our love should Be directed only to the root of all i.e. God. It should be nurtured with care and precaution with a calm spirit of resignation to God. Faith in Vallabhacharya's teaching is a, cardinal principle as in Christianity, to be maintained at all costs and 'risks. Vallabhacharya makes it imperative for-the devotee. On all occasions such as, of misery, evil, sin, lack of devotion, harass-ment from the devotees and the members of one's family, one's masters and servants, in poverty, difficulty of maintenance, sick-ness, ill-treatment by the disciples, opposition from society etc. (V.D.A.-11-13) God should be remembered. One should never be faithless, for, it is a hindrance in religious life. Vallabhacharya is a monotheist in a strict sense of the term. He believes only in Krishna as God. Faith according to him is faith in Krishna only, not even in other incarnations of God or in Gods and godesses. It is a pre-condition to the devotee's getting love for God. Morality

To the Hindu mind, just as light is inseparable from the Sun, so is morality from religion. The Smriti works are considered as Works prescribing the ethical rules for various classes. But they are at a discount now a days. Rules of morality are derived from within, and not from outside. These rules are not static. They have to be changed under new circumstances. Our morality has three aspects. One for one's own self, second for the society in which one lives, and third for the attainment of liberation. First two are relative, but the last one is absolute. Vallabhacharya's approach to morality is from the stand point of devotional life. In this res-pect, he has been influenced by the Gita and the Bhagavata. For him, devotional life presupposes morality. It is rather a seed of devotion. Since devotion is for the love of God, our moral beha-viour must be compatible with love of God. It must be an aid to devotion. In devotional life, they often go hand in hand. If devotion is a substance, it is a shadow. If devotion is the sun, it is its disc. In spite of this, a devotee may have to ignore morality at times, when it hampers his devotional act. Morality should con-duce to the development of religious life. The Gita regards it essential for all religious men, whether men of action of know-ledge, recluses, the Yogins or devotees. While emphasizing its importance, the Gita analyses the concept of morality under cert-ain virtues which are deemed necessary either for devotion or knowledge. In Ch. XII the virtues described are the marks of a devotee and those in Ch. XIII, the marks of a man of knowledge. Dr. Ranade believes that all the moral virtues taught by the Gita are as exemplifications or specifications or exfoliations of the one central virtue of Goddevotion. Virtues o£ a Sthita-Pragna in Ch. II are virtues expected of a devotee. Having stressed the - need of cultivating moral virtues, the Gita says that for God- realisation, one may go beyond morality. (XVII-65). This is called supermoralism. This is to be reached by transcendence of the gunas of Prakriti, which is possible only either by conti-nuous stay in the purified Sattva or by inviolably unswerving devotion called Avyabhicharini Bhakti. This in the language of the Gita is called Bhakti Yoga, whose aim is God realization where there is enjoyment of bliss from touch with GodBrahmasamsparsha. Vallabhacharya appreciates moral virtues only in their being an aid to the service of God. A man may be an ideal moralist, his life may be exemplary to others as a most virtuous man, but if he is cut off from devotional life, his virtues are not worth any salt, for, Vallabhacharya believes that the end of virtues is to realise God. The Gita discriminates between the divine virtues and demonical ones and asserts that the divine virtues are conducive to liberation and demoniacal ones to bon-dage. In his work 'Tattva Dipa Nibandha', he says that although all' moral virtues are worth having, still, if one is not able to practise them all, these three should not be ignored. They are (1) compassion to all creatures, (2) contentment with what you have, and (3) complete restraint over senses. In his work 'Viveka Dhairya Ashraya' he mentions, Discrimination, patience and Refuge in God as chief virtues of a follower of Pushti Marga. Being con-scious of the difficulties in practising the moral virtues, strictly in conformity with the scriptures, he has relaxed their rigidity, by making... allowances in special circumstances, but in acts done with reference to God, he cautions that the moral virtues are to be practised according to one's ability and means or circumstances, but the acts which are not moral should be completely shunned and that the senses should be perfectly Controlled. The sum and substance of all this is that morality is valued only as an aid to devotional life. It must be Helpful in God-realisation. If it interferes with it, then there is nothing wrong in discarding it for, to a devotee love for God and God's love is the only goal of life. Institution of Property

Question of property, whether it should be private or public is a burning question of the present time. In Vallabhacharya's age all property in the possession of an individual was respec-ted as private. The rights of the possessor were not overridden even by the state, but Vallabhacharya's view in this matter is that al-though the property earned by a man is his private property, a devotee who has taken a vow of consecration must regard it as God's property. He is to hold it only as a trustee and use it in the service of God. A devotee has no right to appropriate it for his personal happiness or for the happiness of his family. This does not mean that he has to be indifferent to the needs of himself or of his family. It only means that before using anything which is a devotee's possession, it must be first dedicated to God, and then it should be used as God's favour by him and the members of his family. There is no objection to earning wealth and increasing property, but it should be used only in the service of God and in rendering help to the needy in the name of God. Holding pro-perty is not a sin, but not to use it in God's service, is a sin. It is God's property, and as such, must be used for God's purpose. It is wrong if we believe that we acquire property by our own in-telligence or by the sweat of our brow. Jt is God's will, that a manacquires property. He has, no doubt, to make efforts for it but the reward depends on the will of God. By a vow of consecration, the devotee of Pushti Marga forgoes his title of the ownership of his property and transfers it forever to God. He can, how-ever, spend it in satisfying the minimum of his wants to enable him to render undistracted service of God. This is how Vallabha-charya has removed the evil of private property. Property used in the service of God is not an evil though it is even private. Wealth

He has no objection to the earning of money. A house-holder needs wealth, for the up keeping of his family. He should, earn money in an honest and truthful way by following the profession W his class. Money itself is not an evil but its wrong use is an evil. The Right use of money is to spend it in the service of God. In Tattva Dipa Nibandha, he says that a true devotee should renounce wealth completely, for it is an obstacle in experiencing God's love. If, however, it is not possible to renounce it, it should be used in service of God. Vallabhacharya did not discriminate between the rich and the poor. Society might have created differences among them; but to him, both are equally fit for admission to the path of de-votion, provided they are earnest and pure of heart and sincere believers in God. There were many rich people among his fol-lowers like Raja Ashakarana, Raja Todarmala, Sheth Purushottama of Benares, Birbal, and others; but he was always affec-tionate towards the poor in general. At times, he inquired about their financial circumstances and helped them in their difficulties. He did not consider money as an evil by itself, but exhorted his followers, to earn it in honest and truthful ways and not to be a slave of it. He told them, ―God appreciates better the service of the poor than that of the rich. It is not the means but love behind them, which is of utmost importance in the service of God.‖ He regarded money as a gift of God and, as such, it belonged to God. So it should be used in the service of God. Personally he rigidly adhered to this principle in his own case. He never used any gifts for his personal use. He declined to accept gift even in the form of a large quantity of gold presented to him by king Krishfiarai of Vijayanagar on the occasion of his victory over the Pandits of the Shamkara School in a religious dis-pute. He advised the king to distribute it among the Brahmanas. pne Narharadasa, a Godia Brahmana, earned a lot of money from his business, and requested Vallabhacharya to accept from him a gift of a big amount of money, but he declined and asked him to present it to God Jagannatha. He did not believe in hoard-ing money. His life being simple, his personal wants were very few. Hid could do without money even in extreme need. Most of his followers came from the class that was wedded to poverty. They knew that wealth was a cause of pride which was a great hindrance in devotion. Narandas one of his followers, considered money, as 'refuge'. Santdas Chopada, who had once seen palmy days in his life, by a sudden frown of fortune was reduced to extreme poverty. His daily earning fell low to 2 pice only. Though he was monetarily in extremely straitened circumstances, he did not condescend to accept the gift of gold coins from a fellow, Vaishnava Narandasa. Padmanabhadasa, a Pandit and reciter of the Bhagavata and whose devotion to Vallabhacharya next to God, accepted poverty voluntarily and devoted himself to the service of God. He had so much impoverished himself that he had nothing to present to God as food in his daily service, so he had to present parched gram to the image of the Lord. Vitthaleshji, the son of Vallabhacharya, also followed his father's example. He, no doubt, received gifts from his followers but made them over to God. In conformity with his father's precept, he would not accept ill-gotten money, nor money which he thought proved hindrance in due service of God. He was against hoarding money. Once a big merchant, wished to present him a big amount of money as a gift. He went to see him just at the time when Vitthaleshji was engaged in the divine service. He was disappointed, for, Vitthaleshaji declined his gift, which according to him, was a cause of mental disturbance when he was engaged in God's service. One Kayastha of Surat, who was a Suba to the Emperor of Delhi, made to him an offer of Rupees fifty thousand if he would arrange for his Darshana of Thakurji before its scheduled time, but no response was received from him. Similarly, he refused to accept the big amount of money offered to him as gift by two rich women, Ladbai and Dharbai. One poor man Patel by caste who came to pay his respects to him, along with other rich people was hesitating, because he had nothing to present except a garland of flowers; but Vitthaleshaji himself relieved him of his anxiety by asking for it. The two works—'The stories of Eighty four Vaishnavas' and 'The Stories of Two hundred and fifty two Vaishnavas' are full of such accounts. He believed that earning money or not earning it, depends upon the will of God. If he gets money it is to be used in God's service. If one is poor he should regard his; poverty as a blessing from God; and render service to Him. Service to God does not require means, but only absolute surrender and love for Him. Hospitality

Hospitality is a prominent characteristic of Vallabhacharya's faith. The Gita says, ―A man who eats food without offering it to God is a great sinner. He does not eat food but sin. The food which he eats is nothing but God's gift.‖ Vallabhacharya prohibits every Vaishnava from eating food before its presentation to the image of his Thakorji. It is the duty of Vaishnava not to eat the food presented to God as food, but take it as' God's prasada (favour) which should be shared by other Vaishnavas. A Vaishnava never fails in his welcome recep-tion to another Vaishnava visiting his house as his guest. He ex-pects that some Vaishnavas as guests should bless him by their visit. Even a poor Vaishnava would heartily welcome the day, when a fellow Vaishnava visits his house. He will spare no means in extending his warm welcome to him. Krishnabhatta of Ujjain was well known for his hospitality to the Vaishnavas. He was sad if no Vaishnava was his guest. Being rich, he honoured them with gifts of money and other things needed by them. There is a story recorded in 'The Stories of Two Hundred and Fifty two Vaishnavas' about one couple of Gujarat, whose poverty was so extreme that their daily saving did not exceed a pice. Inspite of their poverty, they did not yield to any one in their hospita-lity to the Vaishnavas. From his daily savings he made a fortune of a rupee, which was spent in purchasing a saree (a garment) for the wife. Now, one day it so happened that some Vaishnavas visited their house. They were in difficulty because they had no means to buy food stuffs for their reception. But the husband with the concurrence of his wife, sold that Saree, and purchased food stuffs, and entertained the visitors, the wife during their stay hours remaining away from the sight of the visitors in a naked pose. There have been examples of the Vaishnava devotees who have preferred starvation to reluctance in hospitality to the Vaishnavas. Such a high sense of hospitality is rare. Art

Vallabhacharya's Pushti Marga is distinguished from other Hindu Religions by its special recognition of Art in religious life. There are various theories about Art. The modern school holds the theory of Art for Art's sake. Ruskiri in the West declared its end to be moral. If art does not lead to moral life, it is not worth having. The Hindu theory of Art in the earliest days of the Vedas was that it must be religious, It must enable one to realise God. It is not meant for demonstration or appreciation or reward. Vallabhacharya's view is that the purpose of Art is to be instru-mental in the service of God- It has no other aim except expe-riencing love, of God by a devotee. The pictures, music, dance etc. have value in so far as they are instrumental in the service of God. Just as the end of knowledge is release from worldly bondage, so the aid of art is release from worldly bondage, not only release, but attainment of God and a blessing of partici-pation in His bliss. In other words, Art is valued by Vallabha-charya only as a means of experiencing or realising God in reli-gious life. In ancient India, every temple had on its walls pictures depicting scenes from the Mahabharat, the Ramayana and the Bhagavata, so that those who saw them had inspiration for religious life. The Vaishnava temples have pictures depicting Krish-na's lilas, described in the Bhagavata. On particular festive oc-casions, screens called Pichawai, with scenes of Krishna's lilas are displayed behind the image of Thakorji in the shrines of Val-labhacharya's faith. The idea behind it is not decoration, but making the devotees remember and contemplate upon God's lilas. Vitthleshji was a great lover of art, not only that, but he himself was a painter. A beautiful picture of Navanita priyaji, his deity, is preserved to this date in the Vaishnava temples of Bombay. On festive occasions beautiful Artis, full of pearls and colours are drawn by the ladies in the shrines. These Artis were originally drawn by the ladies of Vithaleshji's family. During the spring season, the curtains with pictures beautifully drawn, in dried and wet colours are still a characteristic feature of the paintings, indicative of the use of art in the service of God. Similarly, the Sangis also constitute a feature of divine service in the Vaishnava shrines during a particular season. Though art in this school is essentially religious Vallabhacharya does not exclude moral life from the religious. According to him, religious life implies moral. It is not opposed to morality. The pictures of Krishna's lilas evoke love in the heart of a devotee for Him. While he beholds them; his soul feels - that it is in the presence of God. The presentation of Art, on each day, has its specific characteristic according to the occasions of festivals and the seasons. Music

Like painting, music is not for self-pleasure or demonstration or appreciation from others. Vitthalesha himself was a great lover of music. He used to sing his own before his deity. At each time of divine service, music of Kirtans by Suradas, Kumbhanadas, Parmanaddasa, Govindadasa etc. describing Krishna's various lilas is deemed essential. Not only that, but the music for the morning service is not' to be repeated at noon time or evening service. The music selected, fitted the time of service of each day and varied not only according to the days, but also according to the seasons. The matter and the tune both varied. This is a specialty of Vallabhacharya's religion. He was ―fully aware of the idea that Rasa is the soul of poetry, which is variously expressed according to the emotion it involves. Vitthalesha composed some songs in Sanskrit in praise of God and his poet disciples Nandadasa, Govindaswamy, Ghitta Swamy and Chaturbhujadasa composed them in the Vraja Bhasa language. Suradasa and other disciples would sing songs before the deity or the Vaishnavas but not, before non-Vaishnavas. They would not sing even before the princes and the kings under threats or temptations of reward. It is said that one Kumbhanadasa, disci-ple of Vitthaleshji, by Akbara's order, was conducted before him to sing some music, for, his fame as the best singer had reached Akbar's ears and it made him eager to hear him. Kumbhanadasa was reluctant to go but his men forced him to go with them. When he was taken before Akbar at Sikri, the latter asked him to sing some song. He was reluctant to comply, with Akbara's desire but cir-cumstances compelling him, he had to sing a song in which in a direct way he gave him a taunt for asking him to sing. He said, ―I am a devotee of God. I sing only before my God and not before others.‖ Akbar being noble-hearted did not take his reply as an offence, but in appreciation offered him a reward; but he declined and said, ―Oh, emperor, if you are really pleased, do not ask me to sing before you again. My song is only for my God.‖ Similarly Suradasa declined the offer of Akbar to sing something in his praise for which he would get a big reward, but he scorned the reward and scoffed at the very idea of singing for flattery, It is recorded in die life of Govindaswamy, a poet disciple of Vitthaleshaji that one day Akbar, coming to know of Govindswairiy's fame as a singer, desired to listen to his songs; He himself went to Gokula where Govindaswamy was staying, and disguising his identity, listened to his music in Bhairwa raga. Akbar was much impressed, but Govindswamy learnt chat his music was heard by Akbar. He was deeply touched in heart. He was sad because it was heard by a non-Vaishnava. From that day he did not sing before God in that tune. Dance as an art also finds place in the service, of God. Krishna danced with the Gopis. So in imitation of Krishna's. Rasalila, sometimes, performance of the Rasalila enacted on special occasions. From these, one would know that Vallabhacharya's Pushti Marga appreciates Art as a means for experiencing love for God. Apart from that it has no value. Neither Art for Art's sake, nor Art for morality's sake, but for God's sake is his principle. Cow-Protection

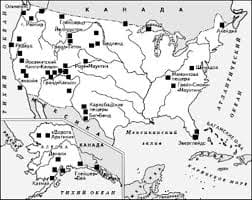

The Sect of Vallabhacharya is well known for cow-protection. God Krishna was a great lover of the cows, and Himself used to graze cows in the forest of Brindavana in the company of the cowherd boys. Of all the animals, the cow is considered as the most sacred by Vallabhacharya and his followers. His son Vitthalanatha was honoured with the title of 'Goswamy'—the protec-tor of Cows, by Emperor Akbar. Appreciating his love for the cows, the Emperor issued a special 'firman' (order) allowing the grazing of Vitthaleshji's cows free of tax and prohibiting cow kill-ing in the locality where he was residing. A similar order was issued prohibiting the killing of birds also. The title of 'Goswami' since then, has. Become hereditary for all the descendants of Vitthaleshji. A noble example of Cow saying from the attack of a lion by his disciple, son of Kumbhanadas has been recorded in the book 'The Stories of Eighty four Vaishnavas'. Although the cow-protection is a very common feature of the Hinduism and the Jainism, it has become a sort of religious sentiment among the followers of Vallabhacharya. It is tantamount to cow- worship. Every Shrine has a Gaushala (a place where the cows are kept and maintained) attached to it. Even in the daily divine service, the cows of metal are considered necessary in place of the living cows, A special day: called Gopashtami— a day for the cow-worship-is celebrated as a festival day, as a token of cow worship, on the eighth day of the month of Kartika every year, His disciples. Suraidasa and others have composed, songs in which Krishna's sports and the grazing of the cows have been reverentially described. Shri Harirayji a descendant of Vallabha-charya, has written a beautiful song m Sanskrit entitled ―Krishna's love for the cows‖. For the benefit of the readers to enable them to understand that Vallabhacharya was an Acharya of liberal views, requiring high standard of behaviour in social and religious life, we shall give heroes ome of his thoughts from his Subodhini on various topics.   ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|