|

|

Text 3. Hryhoriy Skovoroda – a Ukrainian ConfuciusBy Serhiy KHARCHENKO Hryhoriy Skovoroda (1722–1794) has justly been called the most educated, extraordinary and diversified personality in the Slavonic world of the 18th century. He had a perfect command of the Latin, Greek and Hebrew languages, cited the Bible, Aristotle, Plato, and Epicurus. Skovoroda was the last student of the Kyiv Academy who had a chance to polish up his knowledge by visiting European scientific centres. He was a philosopher, expert on the natural sciences, polyglot, poet, artist and musician. Skovoroda could make a good career in any city of the empire. The mighty of this world were eager to employ him like a rich trophy. Skovoroda made two attempts to teach poetics and ethics in Ukrainian colleges. During his lectures he liked to repeat «Every man is what is in his heart». He wanted to foster good virtues in the hearts of his students. However, this point of view contradicted scholastic dogmas of the then official pedagogy and Skovoroda was dismissed. The number of Skovoroda’s works is not adequate to his genius and intellectual potential. He is the author of 17 philosophic works written in the form of dialogues-homilies traditional for that time. In his works Skovoroda researches the ancient world, tells about «true happiness» and creates Utopia – a «mountainous republic» where all people have equal rights. Skovoroda issued a collection of verses called «Garden of Divine Songs» devoted to relevant everyday topics. «Kharkiv Fables» (named after Kharkiv, the city where Skovoroda often resided), like all fables since the time of Aesop criticise human faults. Soviet propaganda interpreted these fables only as «Skovoroda’s protest against the feudal regime and exploiters». That»s why Soviet leaders erected three monuments to Skovoroda, a rare honor for a Ukrainian. This cheerful, active and witty person with a powerful voice (in his young years he sang in the Tsar’s Kapella) and encyclopaedic knowledge could become a good contribution to any high saloon. Many rich countrymen promised to provide «the Ukrainian Socrates» with good working conditions. Perhaps, they were right. Now it is difficult to determine how many works were not written by this «Enlightener of Ukrainian people» due to some circumstances that made him refuse all proposals. One can jokingly say that the writer refused a comfortable table and chose instead an extraordinary and less effective working place – a hollow in a huge tree. The fifty-year-old philosopher suddenly crossed out his past, put the Bible, manuscripts, pipe and violin into a bag and set off «to Ukraine». What were the reasons for such a cardinal decision? Researchers and contemporaries suggested three versions of such withdrawal. Some of them explain Skovoroda’s «whim» by his desire to conceal his rebellious and heretical thoughts under the clothes of «an aged man». In the past, speeches and deeds of Russian vagrant and aged people were not taken into consideration or forgiven. Hryhory Skovoroda had a number of such «sins»: he called courtiers «crocodiles», «monkeys», «snakes» and did not agree with the idea that the world was created by God. Other researchers suggest that Skovoroda followed the famous slogan of Socrates «cognise yourself». Skovoroda was one of a few followers of Jesus who adopted not only the power of his faith but also his life style. During the last 22 years of nomadic life, Skovoroda preached a lot of maxims. He alleged that people should view every day gifted by God as a holiday and to be satisfied with what they had. The philosopher did not summon people to follow his anti-social life. He used to say that one should foster spiritual values and consider the demands of one’s body as secondary after spiritual ones. His listeners were common people and his working place was near the evening fire, a river passage or a crowded trade fair. The 18th century was rather tragic for Ukraine. Ukrainian peasants were enslaved, Zaporizhska Sich, a centuries-old and legendary castle of the Ukrainian Cossacks was destroyed, the nation turned into a mass of silent slaves. Hryhoriy Skovoroda became a spiritual «rebel of the nation». He reminded his humbled countrymen about the greatness of the Ukrainian nation canonising the main spiritual virtues of Ukrainians like love of freedom, power of the will, sincerity and desire to learn. This is the third reason for the philosopher’s withdrawal. Who knows? Maybe the philosopher took the true reasons for his withdrawal to his grave? «The world tried to catch me but failed». This epitaph is placed near his grave. The moral and pedagogical principles of Hryhoriy Skovoroda are close to the teaching of the Chinese philosopher Confucius. Confucius lived 2500 years ago but he is esteemed and honoured in every Chinese family now. So far, Hryhoriy Skovoroda is not so popular with Ukrainians. The heritage of this philosopher is many-sided and relevant today. Hryhoriy Skovoroda struggles for his nation and its people up to this day.

♦ ♦ ♦

Text 4. Lesya Ukrainka A Rebellions Poetes

Lesya Ukrainka is the literary name of Larysa Kosach-Kvitka. She was born in Novograd-Volynskiy to Olga Drahomanova-Kosach (literary name: Olena Pchilka), a writer and publisher in Eastern Ukraine, and Petro Kosach, a senior civil servant. Kosach, an intelligent, well-educated man with non-Ukrainian roots was devoted to the advancement of Ukrainian culture and financially supported Ukrainian publishing ventures. Mykhaylo Drahomanov, Larysa’s maternal uncle, was a noted Ukrainian publicist, historian and scholar. He encouraged her to collect folk songs and folkloric materials, to study history and to peruse the Bible as a source of creative inspiration and eternal themes. Larysa was also influenced by her family’s friendship with Ukraine»s leading cultural figures, such as Mykola Lysenko, a renowned Ukrainian composer and Mykhaylo Starytsky, a popular dramatist and poet. In the Kosach family the mother played the dominant role; at her request, only the Ukrainian language was spoken and, to avoid the schools, in which Russian was the language of instruction, the children had tutors with whom they studied Ukrainian history, literature and culture. Emphasis was also placed on learning foreign languages and reading world literature in the original. In addition to her native Ukrainian, Larysa spoke Russian, Polish, Bulgarian, Greek, Latin, French, Italian, German and English. Unfortunately, the life of this talented woman was rather tragic: at the age of twelve she developed bone tuberculosis, a painful and debilitating disease that she had to fight all her life. Even being physically disabled, Lesya was a woman of rebellious spirit and incredible will power. A precocious child, privileged to live in a highly cultural family, Lesya began writing poetry at the age of nine. When she turned thirteen she saw her first poem published in a journal in L’viv under the name of Lesya Ukrainka, a literary pseudonym suggested by her mother. As a young girl Larysa also showed signs of being a gifted pianist, but her musical studies came to an abrupt end due to her physical disease. Lesya published her first collection of lyrical poetry «On the Wings of Songs» in 1893. Her verses were filled with infinite tenderness and incredible willpower. The poetess deeply sympathised with human sufferings, yet she urged her readers not to submit to the sorrows of life, but to keep fighting for their happiness. In her poem «Contra spem spero!» (Hoping without Hope) the poetess wrote: «Yes! Through my tears I would burst out laughing, Sing a song when a grief is my lot. Ever I, against hope, keep on hoping -I will live! Away, gloomy thought!» Lesya was troubled because her physical disablement prevented her from engaging in the struggle against national and social oppression in Ukraine along with other representatives of the Ukrainian intelligentsia. Her poetry was her weapon: ««Why, my words, aren’t you cold steel, tempered metal, Striking off sparks in the thick of the battle? Why not a sword so relentless and keen That all our foes’ heads would be cut off clean?» When Lesya was a teenager, she often had to go abroad for surgery and therapeutic treatment and was advised to live in countries with a dry climate. Residing for extended periods of time in Germany, Austria, Italy, Bulgaria, Crimea, the Caucasus and Egypt, she studied other peoples’ traditions and culture, and incorporated her observations and impressions into her writings. She turned to new themes and problems, relevant not only to Ukraine but to entire mankind. In her poems «The Babylonian Captivity», «In the Catacombs», «On the Field of Blood», «Vila Sister», «In the Wilderness» the poetess pictured Ancient Greece and Rome, Palestine, Egypt, revolutionary France and medieval Germany. In addition to her lyrical poetry, Lesya Ukrainka wrote poetic drama. A struggler for peace and justice is the main hero of her poems. Erudition, intelligence and knowledge of history and geography helped her trace this image through different epochs and peoples. The best and most famous work of Lesya Ukrainka is her fairy tale «The Forest Song» where she uses mythological characters from Volyn folklore. The poetess wrote this drama the year before her death. The main hero of this tale is a woman struggling for her independence and happiness. Ukrainka depicts the conflict between the high ideal, creative mission and gloomy reality. The Kyiv Opera and Ballet Theatre has staged plays based on Ukrainka’s poetry for many years with great success. Lesya Ukrainka was a well-educated person. She possessed a deep knowledge of world history and literature and devoted her book «The Ancient History of Eastern Peoples’ to her younger sisters. Also, Lesya was a talented translator. She translated the famous works of Homer, Dante, H. Heine, V. Hugo, W. Shakespeare, Lord Byron and A. Mickiewicz. Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko, a contemporary of Lesya Ukrainka wrote about her that she was Ukraine’s best poetess since the time of Shevchenko. He called this physically weak woman «the only real man» in the then Ukraine. Lesya Ukrainka lived at the turn of the 20th century when nobody heard of feminism. She never took part in political rallies or required equal rights with men. She wrote poetry and, thus, managed to prove that woman can contribute to the development of her nation and the world’s culture. Many poems by Lesya Ukrainka have been translated into English, German, French, Spanish and Polish languages. There is a boulevard in central Kyiv named after Lesya Ukrainka. At Kyiv’s square by the same name, one can see a beautiful monument to this notable poetess and woman. Monuments to Lesya Ukrainka can also be found in other countries where there is a Ukrainian Diaspora, for example, in Saskatoon and Toronto (Canada) and in Cleveland (USA). But, perhaps, the best monument to Lesya Ukrainka is her immortal poetry.

♦ ♦ ♦

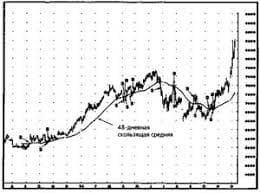

Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|