|

|

Motion and Occupation DrivesThese drives originate in the constitutional circumstances of the animal (its temperament and muscular strength), in its conditional circumstances (the health and the feeding level of the animal), and in its training. In canines living in the wild, these drives are satisfied by the struggle of daily existence, food acquisition, skirmishes with pack mates, and avoiding enemies. Because our house pet doesn’t have to struggle for existence, the intensity of its pressure to release its stored energy in movement—such as going for a walk—or in some sort of work depends on its age, temperament, and physical circumstances. This pressure to do something is more intense in young dogs and in certain breeds.

Figure 3.3 To be a good search and rescue dog, the animal must stay absolutely calm and show self-confidence, even in totally unfamiliar circumstances.

The Six Phases of the Dog’s Search We divide the dog’s searching into the following six phases from the hunting act: • Phase 1: Searching • Phase 2: Locating and working out the odor • Phase 3: Indicating (pointing) as a preliminary to the prey jump • Phase 4: Prey jump • Phase 5: Prey kill and drag-off • Phase 6: Prey sharing

Let’s see now what this will reveal in practice, for instance with searching on debris. The “hunt” of a search and rescue dog, of course, always begins with searching (phase 1) and then finding the human scent and working out the place with the highest concentration of human odor beneath the rubble (phase 2). The dog will locate this place, sometimes stand still for a short time, and then will give an alert (phase 3). The alert can be scratching and/or biting in the rubble in an attempt to take the rubble away. When the rubble isn’t cleared quickly enough, the dog may bark out of irritation. The dog’s location of the scent clue, where the biggest concentration of human odor comes out from beneath the debris, can always be recognized by some specific body position. However, not every dog alerts the same way. Handlers should observe their dog to learn how it communicates its find. Alerts for a Buried Person A dog might be indicating a buried person if it does any of the following: • Suddenly changes direction, makes a curve, or otherwise deviates from a generally straight line during searching • Changes its search tempo, becoming slower or faster • Shows interest in a specific area of the search for somewhat longer • Stands still somewhere, staring into the rubble or snow, or pointing like a hunting dog, looking down while standing with one leg off the ground • Begins to scratch or bite at a particular spot to take away pieces of rubble or snow. However, when a dog only paws once or a few times, it hasn’t ordinarily found the right place. Keep quiet, because the dog is still orienting itself. • Tries by intentional movements to bring its handler to the scent clue. Most of the time, the dog will behave very excitedly and make it clear to the handler, by walking there and back, which direction to go.

Figure 3.4 A dog might be indicating a buried person, or at least the wafted odor of a person, if it suddenly changes direction, makes a curve, or otherwise deviates from a generally straight line during searching.

Alerts with Body Language An alert is how the dog makes it clear to the handler that it has located a missing or buried person during a search. Looking at the dog’s alert in the rubble or in an avalanche, we can always see a certain characteristic behavior. That’s how the handler can recognize that the dog has found the scent clue. In practice it has been clearly proven that dogs react with a certain body attitude or expression upon finding a victim. This reaction is different for every dog. In general, a living victim will be indicated by the dog with an active, cheerful, and confident attitude; dead people will usually be indicated passively, and sometimes with a slightly uncertain behavior. In both cases we can see that the dog is clearly under stress at locating a victim. Search and rescue dog handlers must be able to read their dog’s body language well. Even after a long search under often stressful circumstances, a dog will still use its characteristic behavior to alert. To read the dog, it is particularly important that the handler pay attention to all the changes the dog shows in its behavior. For that, of course, you have to know the dog thoroughly in normal situations, at home as well as during training. This knowledge requires long and close cooperation. Alerts with Barking Barking is the language of the dog. Dogs can produce many different sounds, from deep rolling barking to clear, high-pitched barking and crying. They use their voices to express themselves and change the pitch and volume of the bark to express their emotions and frustrations. Barking doesn’t always mean aggression; it more often means “Are we going to play?” or “Nice that you are here again.” Such “talking” dogs can easily develop the bark as an alert. Barking in itself, however, is not enough as an alert. The dog has to indicate where the highest odor concentration is coming out of the rubble more accurately by pawing or alerting with its nose in the rubble. Easy Barkers During a training week we met a handler who was working with a Collie. The dog was showing remarkable behavior, which was making the handler a bit desperate. The moment he went to work with his dog, it began to bark at the rubble and continued to do so the whole time they worked. This was very confusing, because it was not clear to the handler if it was a real alert or if the dog was only barking out of enthusiasm. We taught his dog to scratch as an alert, and that gave the handler more confidence; later he could hear the difference in the dog’s bark at an alert. We had experienced the same with our Welsh Corgi, which often barked out of enthusiasm when she just had begun to work. After a while, you learn as a handler, and also as a colleague, to notice clear differences between the barking when it is an alert and when not. With our Welsh Corgi, an alert was clear in her body posture and in the way she put her nose deeply in the rubble and began to scratch. Then we knew she had located a victim. Her alert barking was also different from her bark of enthusiasm. Handlers must “read” their dogs and correctly interpret their behavior.

Barking to the Handler When the handler is not standing near the location, then the dog can use the bark to call the handler over. We often see dogs walk toward the handler and make eye contact. Then they bark to the handler and go back to the place where they found the victim in the wilderness search or found the spot with the most human odor coming out of the rubble. This sort of barking is seen in dogs who are easy barkers and “talk” to the dog handler. In this way they tell the dog handler they have found a person. You can see this more often in herding dog breeds, such as Border Collies. These dogs are not focused on the victim, but instead on the dog handler to tell him or her about their find.

Figure 3.5 A dog can bark to call its handler after it finds the odor of a victim.

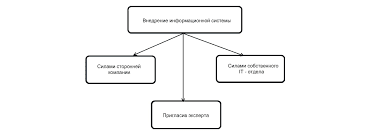

The Replacement Prey At phase 4, the dog makes contact with its prey (the human victim). This step is a critical moment for dogs starting this training method. A dog can’t recognize a human as prey because it is domesticated, and its behavior has changed from that of its wild ancestors. To solve this problem, training victims must always offer the dog a replacement prey when the dog finds them. The dog can expend its drive energy on this object—for our purposes a ball in a long sock—to act out the last phases of its hunting drive complex: shaking, biting to death, and dragging off the prey (phase 5). But what would all of this be without sharing the prey? Retrieving is a form of carrying home the prey. Because the dog has had to search intensively, and also to keep it motivated, we must allow it to act out its total hunting behavior. So the dog has to act out the last part at the end of the hunt: the prey sharing. When the dog brings you the replacement prey, it is time to share a food reward (phase 6). This completes the whole hunting complex for the dog in a satisfying way.   Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|