|

|

IV. Patterning Communicative Behaviour of Language UsersAll types of communication, interpersonal communication, small-group communication and public communication share at least two general characteristics. Communication is dynamic. When we call communication a dynamic process, we mean that all its elements constantly interact with and affect each other. Since all people are interconnected, whatever happens to one person determines in part what happens to others. Like the human interactants who compose them, interpersonal, small-group and public communication relationships constantly evolve from and affect one another. Nothing about communication is static. Everything is accumulative. We communicate as long as we live, and thus every interaction that we engage in is a part of connected happenings. In other words, all our present communication experiences may be thought of as points of arrival from past encounters and as points of departure for further ones. Communication is unrepeatable and irreversible. Every human contact we experience is unique. It has never happened before, and never again will it happen in just the same way. One interpretation of the old adage “You can never step into the same river twice” is that the experience and time changes both you and the river forever. Similarly, a communication encounter affects and changes the interactants so that the encounter can never happen in exactly the same way again. Thus communication is both unrepeatable and irreversible. We can neither “take back” anything we have said nor “erase” the effects of something we have done. And although we may be greatly influenced by our past, we can never reclaim it. In the words of an old Chinese proverb, “Even the emperor cannot buy back one single day”. How are we supposed to study communication then, if it is dynamic, unrepeatable and irreversible? Modelling as always is the best way out. In the first unit we discussed the scientific approach to language in general and the idea of language modelling. We illustrated these notions by using the model that regards language as a structure and system of units, as a functioning mechanism. Structural integrity and purposefulness of the mechanism provide language with the capacity of being an adequate means of communication. This functional view upon language which we adopted for our sample modelling, gave scholars the possibility to penetrate into the laws and regularities of language as a whole, as well as into the functions and interrelations of its constituent parts, or language units like phonemes, morphemes, words, sentences and texts. These language units were abstracted from the language structure on the basis of their specific system building functions, like differentiation, nomination, identification, etc. The ideal model thus received was deduced from our initial hypothetic assumption that language is a means of communication, functioning irrespective of its users and circumstances. Now let us look at language from a different perspective. Let us focus on the various functions of the language mechanism in the life of human society, in other words, on the patterning of communicative behavior of language users. This, communicative approach to language modelling, was escaping structural linguistics of the beginning of the 20th century mainly because the clarification and interpretation of the communicative process calls for the study of a wide range of scientific domains, those outside the language structure proper. When studying language as it functions for definite interpersonal contacts, as it is used within a particular society, culture, group, or context, we evidently need to introduce and explore some psychological, cultural, sociological, or ethnographic knowledge. All these domains are directly related to humans, together with linguistics they study human beings and their behaviour, communication including. This common object unites linguistics and other sciences as anthropological ones. The term anthropology comes from Greek. It means the science of man, the study of man in relation to distribution, origin, classification, and relationship of races, physical character, environmental and social relations, and culture. When linguists adopted this attitude to language as a facet of social relation, they therefore launched the so called anthropological linguistics which is not really a special branch of language studies, but rather a special point of view upon language, its structure, patterning and functions. This shift of the focus of studies from system to the user of this system might be called anthropocentric as it considers man to be the most important entity of linguistic explorations. Let us put it in other words. The ways in which the various schools of linguistics regard language divide up this science into two types. Microlinguistics (or linguistics proper). It deals with the structure of message independent of the characteristics of either speakers or hearers. Microlinguistics prevailed in science in the 1950s and 1970s carrying on the ideas of N. Chomsky of looking at language in abstraction, as an independent system governed by rules. These rules were described in the transformational theory and its later developments which showed no interest in how, in pursuing various social purposes, interactants combine utterances. Structural linguistics devised the theory of inner rules of language, but it did not recognize that language is used by people for doing something, for realizing activity. Macrolinguistics (or metalinguistics, or exolinguistics). It covers all other aspects of language study which concern relations between the characteristics of messages and the characteristics of individuals who produce and receive them, including both, their behavior and culture. Macrolinguistics is concerned with all psychological and social influence upon the selection, use and interpretation of language (messages): attitudes, cultural meanings, social roles, values, etc. Therefore, macrolinguistics is basically a language activity, or human communication. At present the term communicative linguistics is widely used to denote this field of linguistic knowledge. As with any other scientific deductive approach, we need to adopt a hypothesis, a starting point of our exploration of the communicative linguistics. Let me suggest the following assumption: language is an activity and a form of social behaviour. The process of the verification of this statement and anthropological modelling of language from this perspective are then the goals of our further inquiry. In order to understand the prerequisites of language activity (communication), and to comprehend its essence, let us begin with the following question: Why, when and how do people use language? To answer this question let us take a simple communicative episode from our everyday activities. Imagine that you have an appointment with a friend, that you do not want to be late, but you do not know what time it is. You ask someone who has a watch and get the answer. The communicative episode is completed. Now we shall try to model it in terms of constituents and causes. Speakers use language to express their thoughts and to influence others. Even when we talk to ourselves (in case of inner speech), we subconsciously pursue the same goal: to influence, but in this case ourselves. Therefore, communication demands at least two participants of the process: addresser (otherwise called source or speaker) and addressee (otherwise called receiver or listener). Both the addresser and the addressee may be individual and collective: people may speak on behalf of a group, co-author their messages, address them to large audiences or even unknown prospective receivers. But in any case both, addressers and addressees possess certain psychological and social characteristics, like age, education, ethnicity, political and other views, social status and others. All of them to some extent influence the mode and content of communication and should be considered in our model. These are the first two prerequisites of communication which can function under certain circumstances or conditions. In the most general sense, we have communication whenever one system, a source, influences another system, a receiver, by manipulation of the signals which can be carried in the channel connecting them. For example, in the telephone communication system the messages produced by a speaker are in the form of variable sound pressures and frequences carried over wire (channel) to a receiver to be utilized by him. Channel is an essential component of the communicative model. Channels through which information is transmitted may be oral or written; direct (face-to-face) or indirect (radio, telephone conversation, letters which represent indirect communication suspended in time). Anything that produces unpredictable interference in the channel may be called noise. This general model of the communication process used in the theory of information, however, does not provide us with a satisfactory picture of human communication as it disregards individual human functions in the process; it is not designed to take into account the meaning of signals, i.e., their significance when viewed from the receiving side, and their intention when viewed from the addresser's side. Therefore, we need to supplement our model of communication with several other prerequisites. People do not embark on communication without any strong reason, or inducement. In my example above, the person had no watch but did not want to be late for the appointment. This inducement for communication may be called a motive – something (as a need or desire) that causes a person to speak, a stimulus to communication. Motive is a psychological category as it characterizes the state of mind, i.e., an individual’s idea which urges him or her to speak. The motive further leads a person to a certain intention to reach a desired end. In the example above, the person needed to know what time it was. Intention is a determination to act in a certain way, to speak in order to achieve something, and thus it can be viewed as a derivative of a motive, a design of action aimed at bringing about a desired goal. Evidently, one motive may cause different intentions, which depend on the personality of the addresser and the circumstances of communication. Hence, intention also belongs to the domain of communicators’ psychology and constitutes another unit of our model of communication. Communication occurs in a certain place, at some period of time, under some essential circumstances which facilitate or hamper it, like family circle orstreet crowd, friendly face-to-face encounter or public presentation at a conference. All these surrounding circumstances of physical and social origin are called a communicative setting (another term being communicative situation). Any user of a language knows how much setting matters for our language strategies and manners, and hence, we include setting in the model of communication. All the above discussed constituents as one entity make up the model of the communication process, an episode of human interactivity. This model may be diagrammed in the following way: motive – intention – addresser – channel - addressee I Noise I Setting The fragment of activity represented in this diagram has acquired different terminological names in communicative linguistics. They are: communicative episode, communicative act, speech action, to name a few. But whatever terms are applied, the concept of human communicative activity remains intact. Different scholars, certainly, modify, reduce or specify the model and its components, which is but natural in any science, but nevertheless the anthropological communicative approach to this language unit can neither be denied nor blurred. When linguists adopt the communicative point of view on language they inevitably have to focus on social, cultural, psychological, and ethnic conditions or aspects of language behavior of individuals and whole speech communities because these aspects are indicative of variable speech strategies and have an explanatory force. The general theory developed on these methodological premises has been often referred to as the theory of speech activity. This is a generic term for a number of theoretical disciplines and related branches of language exploration. I will discuss each of them in more detail in the lectures. Here I shall permit myself one remark concerning the historical roots of the theory of speech activity. Though this theory as a trend in linguistics appeared and was recognized as such in the second half of the 20th century, linguists of older generations were not indifferent to the problems of communication and human communicative behavior. Actually, the track for modern explorations was laid by outstanding thinkers earlier. Among the founding fathers of the theory of speech activity, we should name a great German linguist and philosopher of language W.von Humboldt who introduced the notion of language as activity and initiated numerous studies of language in the context of culture, national spirit, and ethnicity. Humboldt thus postulated the exploration of language “extensively”, i.e., in the framework of sociology, psychology, ethnography and other related fields which actually predetermine the existence of functioning language, or activity. The modern theory of speech activity exists as aset of linguistic schools or branches. The separation of these domains depends on their particular interests in either the psychological aspect of speech (we use the term speech as synonymous to language activity), or its social background, or its relation to culture, etc. Though all these foci are interrelated (as they study communication in a wider context than structural studies do), each of the branches answers a number of specific basic questions and views speech as a psychological, social, pragmatic, or cultural phenomenon. Let me explain this point with the following example. When a scholar is interested in the process of speech production as a mental phenomenon, and when the motives and intentions of speakers are studied alongside with the work of the mind, the mechanism of thinking, then this scholar represents the domain of psycholinguistics. When a scholar is interested in the speech strategies of a speaker pursuing certain communicative intentions, then we encounter a representative of pragmalinguistics. The interest in social variability of speech brings about the study called sociolinguistics. A survey of the special goals and methods of language exploration within these complex disciplines constitutes the subject of our further discussion. V. Further Reading From: Ch.E. Osgood and Th.A. Sebeok. Models of the Communication Process// Psycholinguistics. A Survey of Theory and Research Problems. Ed. by Ch. Osgood and Th.Sebeok, Bloomfield and L.: Indiana. University Press, 1967. – P.62-63. Human communication is chiefly a social affair. Any adequate model must therefore include at least two communicating units, a source unit (speaker) and a destination unit (hearer). Between any two such units, connecting them into a single system is what we may call the message. We will define message as that part of the total output (responses) of a source unit which simultaneously may be a part of the total input (stimuli) to a destination unit. When individual A talks to individual B, for example, his postures, gestures, facial expressions and even manipulations with objects may all be part of the message, as of course are events in the sound wave channel. But other parts of A’s total behaviour (e.g., breathing, thinking) may not affect B at all – these events are not part of the message as we use the term. These message events (reactions of one individual that produce stimuli for another) may be either immediate or mediate – ordinary face-to-face conversation illustrates the former and written communication illustrates the latter. Figure 2-1 presents a model of the essential communication act, encoding of a message by a source unit and decoding of that message by a destination unit. Since the distinction between source and destination within the same communicator seems relevant only with respect to the direction of information exchange (e.g., whether the communicator is decoding or encoding), we substitute the single term mediator for that system which intervenes between receiving and transmitting operations. The way in which the various sciences concerned with human communication impinge upon and divide up the total process can be shown in relation to this figure. Exolinguistics Microlinguistics ____________________ Phonetics Psychoacoustics Source unit Destination unit Input-Receiver-Mediator-Trans---Message-Receiver-Mediator-Trans--Output mitter mitter (output) (input) Encoding------------------------Decoding ___________ _____________ Psycholinguistics Social sciences ___________-------------------__________ Communications

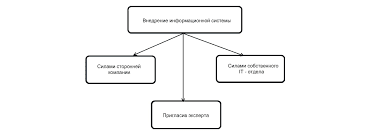

Figure 2-1. Model of the essential communication act.   Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|