|

|

Surrounding the Panama Canal

There is a little shirt shop in Colon, Panama, on Calle 10a between Avenida Herrera and Avenida Amador Guerrero, whose red and black painted shingle announces that Lola Osawa is the proprietor. Across the street from her shirt shop, where the red light district begins, is a bar frequented by natives, soldiers and sailors. Tourists seldom go there, for it is a bit off the beaten track. In front of the bar is a West Indian boy with a tripod and camera with a telescopic lens. He never photographs natives, and wandering tourists pass him by, but he is there every day from eight in the morning until dark. His job is to photograph everyone who shows an undue interest in the little shirt shop and particularly anyone who enters or leaves it. Usually he snaps your picture from across the street, but if he misses you he darts across and waits to take another shot when you come out. I saw him take my picture when I entered the store. It was almost high noon and Lola was not yet up. The business upon which she and her husband are supposed to depend for a living was in the hands of two giggling young Panamanian girls who sat idly at two ancient Singer sewing machines. "You got shirts?" I asked. Without troubling to rise and wait on me, they pointed to a glass case stretched across the room and barring quick entrance [57]to the shop proper. I examined the assortment in the case, counting a total of twenty-eight shirts. "I don't especially like these," I said. "Got any others?" "No more," one of them giggled. "Where's Lola?" "Upstairs," the other said, motioning with her thumb to the ceiling. "Looks like you're doing a rushing business, eh?" They looked puzzled and I explained: "Busy, eh?" "Busy? No. No busy." There is little work for them and neither Lola nor they care a whoop whether or not you buy any of the shop's sk of twenty-eight shirts. Lola herself pays little attention to the business from which she obviously cannot earn enough to pay the rent, let alone keep herself and her husband, pay two girls and a lookout. The little shirt shop is a cubbyhole about nine feet square, its wooden walls painted a pale, washed-out blue. A deck which cuts the store's height in half, forms a little balcony which is covered by a green and yellow print curtain stretched across it. To the right, casually covered by another print curtain, is a red painted ladder by which the deck is reached. On the deck, at the extreme left, where it is not perceptible from the street or the shop, is another tiny ladder which reaches to the ceiling. If you stand on the ladder and press against the ceiling directly over it, a well-oiled trap door will open soundlessly and lead you into Lola's bedroom above the shop. In front of the window with the blue curtain is a worn bed, the hard mattress neatly covered with a counterpane. At the head of the mattress is a mended tear. It is in this mattress that Lola hides photographs of extraordinary military and naval importance. I saw four of them. The charming little seamstress is one of the most capable of the [58]Japanese espionage agents operating in the Canal Zone area. Lola Osawa is not her right name. She is Chiyo Morasawa, who arrived at Balboa from Yokahama on the Japanese steamship "Anyo Maru" on May 24, 1929, and promptly disappeared for almost a year. When she appeared again, she was Lola Osawa, seamstress. She has been an active Japanese agent for almost ten years, specializing in getting photographs of military importance. Her husband, who entered Panama without a Panamanian visa on his passport, is a reserve officer in the Japanese Navy. He lives with Lola in the room above the shop, never does any work though he passes as a merchant, and is always wandering around with a camera. Occasionally he vanishes to Japan. His last trip was in 1935. At that time he stayed there over a year. To defend the ten-mile-wide and forty-six-mile-long strip of land, lakes and canal which the Republic of Panama leased to the United States "in perpetuity," the army, navy and air corps have woven a network of secret fortifications, laid mines and placed anti-aircraft guns. Foreign spies and international adventurers play a sleepless game to learn these military and naval secrets. The Isthmus is a center of intrigue, plotting, conniving, conspiracy and espionage, with the intelligence departments of foreign governments bidding high for information. For the capture or disablement of the Canal by an enemy would mean that American ships would have to go around the Horn to get from one coast to another—a delay which in time of war might prove to be the difference between victory and defeat. Because of the efficiency and speed of modern communication and transportation, any region within five hundred to a thousand miles of a military objective is considered in the "sensitive zone," especially if it is of great strategic importance. Hence, espionage activities embrace Central and South American Republics which [59]may have to be used by an enemy as a base of operations. Costa Rica, north of the Canal, and Colombia, south of it, are beehives of secret Japanese, Nazi and Italian activities. Special efforts are made to buy or lease land "for colonization," but the land chosen is such that it can be turned into an air base almost overnight. For decades Japanese in the Canal Zone area have been photographing everything in sight, not only around the Canal, but for hundreds of miles north and south of it; and the Japanese fishing fleet has taken soundings of the waters and harbors along the coast. Since the conclusion of the Japanese-Nazi "anti-Communist pact," Nazi agents have been sent to German colonies in Central and South America to organize them, carry on propaganda and cooperate secretly with Japanese agents. Italy, which had been only mildly interested in Central America, has become extremely active in cultivating the friendship of Central American Republics since she joined the Tokyo-Berlin tie-up. Let me illustrate: The recognized vulnerability of the Canal has caused the United States to plan another through Nicaragua. The friendship of the Nicaraguan Government and people, therefore, is of great importance to us from both a commercial and a military standpoint. It is likewise of importance to others. Italy undertook to gain Nicaragua's friendship when she joined the Japanese-Nazi line-up. First, she offered scholarships, with all expenses paid, for Nicaraguan students to study fascism in Italy. Then, on December 14, 1937, about one month after a secret Nazi agent arrived in Central America with orders to step on the propaganda and organizational activity, the Italian S.S. "Leme" sailed out of Naples with a cargo of guns, armored cars, mountain artillery, machine guns and a considerable amount of munitions. On January 11, 1938, the Secretary of the Italian Legation in San Josй, Costa Rica, flew to Managua, Nicaragua, to witness [60]the delivery of arms which arrived in Managua on January 12, 1938. Diplomatic representatives do not usually witness purely business transactions, but this was a shipment worth $300,000 which the Italian Government knew Nicaragua could not pay. But, as one of the results, Italy today has a firm foothold in the country through which the United States hopes to build another Canal. The international espionage underground world, which knew that the shipment of arms was coming, has it that Japan, Germany and Italy split the cost of the arms among themselves to gain the friendship of the Nicaraguan Government. A flood of Nazi propaganda sent on short-wave beams is directed at Central and South America from Germany. In Spanish, German, Portuguese and English, regular programs are sent across at government expense. Government subsidized news agencies flood the newspapers with "news dispatches" which they sell at a nominal price or give away. The programs and the "news dispatches" explain and glorify the totalitarian form of government, and since many of the sister "republics" are dictatorships, they are ideologically sympathetic and receptive. The Nazis are strong in Colombia, south of the Canal, with a Bund training regularly in military maneuvers at Cali. Since the Japanese-Nazi pact, the Japanese have established a colony of several hundred at Corinto in the Cauca Valley, thirty miles from Cali. The Japanese colony was settled on land carefully chosen—long, level, flat acres which overnight can be turned into an air base for a fleet landed from an airplane carrier or assembled on the spot. And it is near Cali that Alejandro Tujun, a Japanese in constant touch with the Japanese Foreign Office, is at this writing dickering for the purchase of 400,000 acres of level land for "colonization." On such an acreage enough military men could be colonized to give the United States a first-class headache in time of war. It is two hours flying time from Cali to the Canal. [61]The entrances on either side of the Panama Canal are secretly mined. The location of these mines is one of the most carefully guarded secrets of the American navy and one of the most sought after by international spies. The Japanese, who have been fishing along the West Coast and Panamanian waters for years, are the only fishermen who find it necessary to use sounding lines to catch fish. Sounding lines are used to measure the depths of the waters and to locate submerged ledges and covered rocks in this once mountainous area. Any fleet which plans to approach the Canal or use harbors even within several hundred miles north or south of the Canal must have this information to know just where to go and how near to shore they can approach before sending out landing parties. The use of sounding lines by Japanese fishermen and the mysterious going and comings of their boats became so pronounced that the Panamanian Government could not ignore them. It issued a decree prohibiting all aliens from fishing in Panamanian waters. In April, 1937, the "Taiyo Maru," flying the American flag but manned by Japanese, hauled up her anchor in the dead of night and with all lights out chugged from the unrestricted waters into the area where the mines are generally believed to be laid. The "Taiyo" operated out of San Diego, California, and once established a world's record of being one hundred and eleven days at sea without catching a single fish. The captain, piloting the boat from previous general knowledge of the waters rather than by chart, unfortunately ran aground. The fishing vessel was stranded on a submerged ledge and couldn't get off. In the morning the authorities found her, took off her captain and crew—all of whom had cameras—and asked why the boat was in restricted waters. [62]"I didn't know where I was," said the captain. "We were fishing for bait." "But bait is caught in the daytime by all other fishermen," the officials pointed out. "We thought we might catch some at night," the captain explained. Since 1934, when rumors of the Japanese-Nazi pact began to circulate throughout the world, the Japanese have made several attempts to get a foothold right at the entrance to the Canal on the Pacific side. They have moved heaven and earth for permission to establish a refrigeration plant on Taboga Island, some twelve miles out on the Pacific Ocean and facing the Canal. Taboga Island would make a perfect base from which to study the waters and fortifications along the coast and the islands between the Canal and Taboga. When this and other efforts failed and there was talk of banning alien fishing in Panamanian waters, Yoshitaro Amano, who runs a store in Panama and has far flung interests all along the Pacific coasts of Central and South America, organized the Amano Fisheries, Ltd. In July, 1937, he built in Japan the "Amano Maru," as luxurious a fishing boat as ever sailed the seas. With a purring diesel engine, it has the longest cruising range of any fishing vessel afloat, a powerful sending and receiving radio with a permanent operator on board, and an extremely secret Japanese invention enabling it to detect and locate mines. Like all other Japanese in the Canal Zone area, Amano, rated a millionaire in Chile, goes in for a little photography. In September, 1937, word spread along the international espionage grapevine that Nicaragua, through which the United States was planning another Canal, had some sort of peculiar fortifications in the military zone at Managua. [63]Shortly thereafter the Japanese millionaire appeared at Managua with his expensive camera and headed straight for the military zone. Thirty minutes after he arrived (8:00 A.M. of October 7, 1937), he was in a Nicaraguan jail charged with suspected espionage and with taking pictures in prohibited areas. I mention this incident because the luxurious boat was registered under the Panamanian flag and immediately began a series of actions so peculiar that the Republic of Panama canceled the Panamanian registry. The "Amano" promptly left for Puntarenas, Costa Rica, north of the Canal, which has a harbor big enough to take care of almost all the fleets in the world. Many of the Japanese ships went there, sounding lines and all, when alien fishing was prohibited in Panamanian waters. Today the "Amano Maru" is a mystery ship haunting Puntarenas and the waters between Costa Rica and Panama and occasionally vanishing out to sea with her wireless crackling constantly. Some seventy fishing vessels operating out of San Diego, California, fly the American flag. San Diego is of great importance to a potential enemy because it is a naval as well as an air base. Of these seventy vessels flying the American flag, ten are either partially or entirely manned by Japanese. Let me illustrate how boats fly the American flag: On March 9, 1937, the S.S. "Columbus" was registered as an American fishing vessel under certificate of registry No. 235,912, issued at Los Angeles. The vessel is owned by the Columbus Fishing Company of Los Angeles. The captain, R.I. Suenaga, is a twenty-six-year-old Japanese, born in Hawaii and a full-fledged American citizen. The navigator and one sailor are also Japanese, born in Hawaii but American citizens. The crew of ten consists entirely of Japanese born in Japan. The ten boats which fly the American flag but are manned by Japanese crews are: "Alert," "Asama," "Columbus," "Flying [64]Cloud," "Magellan," "Oipango," "San Lucas," "Santa Margarita," "Taiyo," "Wesgate." Each boat carries a short-wave radio and has a cruising range of from three to five thousand miles, which is extraordinary for just little fishing boats. They operate on the high seas and where they go, only the master and crew and those who send them know. The only time anyone gets a record of them is when they come in to refuel or repair. In the event of war half a dozen of these fishing vessels, stretched across the Pacific at intervals of five hundred or a thousand miles, would make an excellent system of communication for messages which could be relayed from one to another and in a few moments reach their destination. In Colуn on the Atlantic side and in Panama on the Pacific, East and West literally meet at the crossroads of the world. The winding streets are crowded with the brown and black people who comprise three-fourths of Panama's population. On these teeming, hot, tropical streets are some three hundred Japanese storekeepers, fishermen, commission merchants and barbers-few of whom do much business, but all of whom sit patiently in their doorways, reading the newspapers or staring at the passer-by. I counted forty-seven Japanese barbers in Panama and eight in Colуn. In Panama they cluster on Avenida Central and Calle Carlos A. Mendoza. On both these streets rents are high and, with the exception of Saturdays when the natives come for haircuts, the amount of business the barbers do does not warrant the three to five men in each shop. Yet, though they earn scarcely enough to meet their rent, there is not a lowly barber among them who does not have a Leica or Contax camera with which, until the sinking of the "Panay," they wandered around, photographing the Canal, the islands around the Canal, the coast line, and the topography of the region. [65]They live in Panama with a sort of permanence, but nine out of ten do not have families—even those advanced in years. Periodically some of them take trips to Japan, though, if you watch their business carefully, you know they could not possibly have earned enough to pay for their passage. And those in the outlying districts don't even pretend to have a business. They just sit and wait, without any visible means of support. It is not until you study their locations, as in the Province of Chorrera, that you find they are in spots of strategic military or naval importance. Since there were so many barbers in Panama, the need for an occasional gathering without attracting too much attention became apparent. And so the little barber, A. Sonada, who shaves and cuts hair at 45 Carlos A. Mendoza Street, organized a "labor union," the Barbers' Association. The Association will not accept barbers of other nationalities but will allow Japanese fishermen to attend meetings. They meet on the second floor of the building at 58 Carlos A. Mendoza Street, where many of the fishermen live. At their meetings one guard stands outside the room and another downstairs at the entrance to the building. On hot Sunday afternoons when the Barbers' Association gathers, the diplomatic representatives of other nations are usually taking a siesta or are down at the beach, but Tetsuo Umimoto, the Japanese Consul, climbs the stairs in the stuffy atmosphere and sits in on the deliberations of the barbers and visiting fishermen. It is the only barbers' union I ever heard of whose deliberations were considered important enough for a diplomatic representative to attend. This labor union has another extraordinary custom. It has a special fund to put competitors up in business. Whenever a Japanese arrives in Panama, the Barbers' Association opens a shop for him, buys the chairs-provides him with everything necessary to compete with them for the scarce trade in the shaving and shearing industry! At these meetings the barber Sonada, who is only a hired [66]hand, sits beside the Japanese Consul at the head of the room. Umimoto remains standing until Sonada is seated. When another barber, T. Takano, who runs a little hole-in-the-wall shop and lives at 10 Avenida B, shows up, both Sonada and the Consul rise, bow very low and remain standing until he motions them to be seated. Maybe it's just an old Japanese custom, but the Consul does not extend the same courtesy to the other barbers. In attendance at these guarded meetings of the barbers' union and visiting fishermen, is Katarino Kubayama, a gentle-faced, soft-spoken, middle-aged businessman with no visible business. He is fifty-five years old now and lives at Calle Colуn, Casa No. 11. Way back in 1917 Kubayama was a barefoot Japanese fisherman like the others now on the west coast. One morning two Japanese battleships appeared and anchored in the harbor. From the reed-and vegetation covered jungle shore, a sun-dried, brown panga was rowed out by the barefooted fisherman using the short quick strokes of the native. His brown, soiled dungarees were rolled up to his calves; his shirt, open at the throat, was torn and his head was covered by a ragged straw hat. The silvery notes of a bugle sounded. The crew of the flagship lined up at attention. The officers, including the Commander, also waited stiffly at attention while the fisherman tied his panga to the ship's ladder. As Kubayama clambered on board, the officers saluted. With a great show of formality they escorted him to the Commander's quarters, the junior officer following behind at a respectful distance. Two hours later Kubayama was escorted to the ladder again, the trumpet sounded its salute, and the ragged fisherman rowed away—all conducted with a courtesy extended only to a high ranking officer of the Japanese navy. Today Kubayama works closely with the Japanese Consul. [67]Together they call upon the captains of Japanese ships whenever they come to Panama, and are closeted with them for hours at a time. Kubayama says he is trying to sell supplies to the captains. Japanese in the Canal Zone area change their names periodically or come with several passports all prepared. There is, for instance, Shoichi Yokoi, who commutes between Japan and Panama without any commercial reasons. On June 7, 1934, the Japanese Foreign Office in Tokyo issued passport No. 255,875 to him under the name of Masakazu Yokoy with permission to Visit all Central and South American countries. Though he had permission for all, he applied only for a Panamanian visa (September 28, 1934), after which he settled down for a while among the fishermen and barbers. On July 11, 1936, the Foreign Office in Tokyo handed Yokoy another passport under the name of Shoichi Yokoi, together with visas which filled the whole passport and overflowed onto several extra pages. Shoichi or Masakazu is now traveling with both passports and a suitcase full of film for his camera. Several years ago a Japanese named T. Tahara came to Panama as the traveling representative of a newly organized company, the Official Japanese Association of Importers and Exporters for Latin America, and established headquarters in the offices of the Boyd Bros. shipping agency in Panama. Nelson Rounsevell, publisher of the Panama American, who has fought Japanese colonization in Canal areas, printed a story that this big businessman got very little mail, made no efforts to establish business contacts and, in talking with the few businessmen he met socially, showed a complete lack of knowledge about business. Tahara was talked about and orders promptly came through for him to return to Japan. This was in 1936. Half a year later, a suave Japanese named Takahiro Wakabayashi appeared in Panama as the representative [68]of the Federation of Japanese Importers and Exporters, the same organization under a slightly changed name. Wakabayashi checked into the cool and spacious Hotel Tivoli, run by the United States Government on Canal Zone territory and, protected by the guardian wings of the somewhat sleepy American Eagle, washed up and made a beeline for the Boyd Bros. office, where he was closeted with the general manager for over an hour. Wakabayashi's business interests ranged from taking pictures of the Canal in specially chartered planes, to negotiating for manganese deposits and attempting to establish an "experimental station to grow cotton in Costa Rica." The big manganese-and-cotton-photographer man fluttered all over Central and South America, always with his camera. One week he was in San Josй, Costa Rica; the next he made a hurried special flight to Bogotб, Colombia (November 12, 1937); then back to Panama and Costa Rica. He finally got permission from Costa Rica to establish his experimental station. In obtaining that concession he was aided by Giuseppe Sotanis, an Italian gentleman wearing the fascist insignia in the lapel of his coat, whom he met at the Gran Hotel in San Josй. Sotanis, a former Italian artillery officer, is a nattily dressed, slender man in his early forties who apparently does nothing in San Josй except study his immaculate finger nails, drink Scotch-and-sodas, collect stamps and vanish every few months only to reappear again, still studying his immaculate finger nails. It was Sotanis who arranged for Nicaragua to get the shipment of arms and munitions which I mentioned earlier. This uncommunicative Italian stamp collector paved the way for Wakabayashi to meet Raul Gurdian, the Costa Rican Minister of Finance, and Ramon Madrigal, Vice-president of the government-owned National Bank and a prominent Costa Rican merchant. Shortly after Costa Rica gave Wakabayashi permission to experiment with his cotton growing, both the Minister of [69]Finance and the Vice-president of the government bank took trips to Japan. The ink was scarcely dry on the agreement to permit the Japanese to experiment in cotton growing before a Japanese steamer appeared in Puntarenas with twenty-one young and alert Japanese and a bag of cotton seed. They were "laborers," Wakabayashi explained. The "laborers" were put up in first-class hotels and took life easy while Wakabayashi and one of the laborers started hunting a suitable spot on which to plant their bag of seed. All sorts of land was offered to them, but Wakabayashi wanted no land anywhere near a hill or a mountain. He finally found what he wanted half-way between Puntarenas and San Josй—long, level, flat acres. He wanted this land at any price, finally paying for it an annual rental equal to the value of the acres. The twenty-one "laborers" who had been brought from Chimbota, Peru, where there is a colony of twenty thousand Japanese, planted an acre with cotton seed and sat them down to rest, imperturbable, silent, waiting. The plowed land is now as smooth and level as the acres at Corinto in Colombia, south of the Canal. The harbor at Puntarenas, as I mentioned earlier, would make a splendid base of operations for an enemy fleet. Not far from shore are the flat, level acres of the "experimental station" and the twenty-one Japanese who could quickly turn these smooth acres into an air base. It is north of the Panama Canal and within two hours flying time of it, as Corinto is south of the Canal and within two hours flying time. The Boyd Bros. steamship agency, to which Tahara and Wakabayashi went immediately upon arrival, is an American concern. The manager, with whom each was closeted, is Hans Hermann Heildelk of Avenida Peru, No. 64, Panama City, and, though efforts have been made to keep it secret, part owner of the [70]agency. Heildelk is also the son-in-law of Ernst F. Neumann, the Nazi Consul to Panama. On November 15, 1937, Heildelk returned from Japan by way of Germany. Five days later, on November 20, 1937, his father-in-law, who, besides being Nazi Consul, owns in partnership with Fritz Kohpcke, one of the largest hardware stores in Panama, told his clerks that he and his partner would work a little late that night. Neither partner went out to eat and the corrugated sliding door of the store, at Norte No. 54 in the heart of the Panamanian commercial district, was left open about three feet from the ground so that passers-by could not see inside unless they stooped deliberately. At eight o'clock a car drew up at the corner of the darkened street in front of Neumann & Kohpcke, Ltd. Two unidentified men, Heildelk and Walter Scharpp, former Nazi Consul at Colуn who had also just returned from Germany, stepped out, and stooping under the partly open door, entered the store. Once inside Scharpp quietly assumed command. To all practical purposes they were on German territory, for the Nazi consulate office was in the store. Scharpp announced that the group had been very carefully chosen because of their known loyalty to Nazi Germany and because of their desire to promote friendship for Germany in Latin American countries and to cooperate with the Japanese, who had their own organization functioning efficiently in Central and South America. "Some of these countries are already friendly," said Scharpp, "and we can work undisturbed provided we do not interfere in the Panama Canal Zone. It is North American territory, and you will have trouble from their officials and intelligence officers as well as political pressure from the States. You understand?" "Panama is friendly to North America," said Kohpcke. [71]"Precisely. At the present time it is not wise to do much more than broadcast, but at a propitious time we shall be able to explain National Socialism to the Panamanians." He looked at Kohpcke, whose left eyelid droops more than his right, giving him the appearance of being perpetually sleepy. Kohpcke looked at Neumann. "Tonight we want to organize a Bund in Panama. In a few days I am going to Costa Rica to organize another and then leave for Valparaiso." The others nodded. They had been informed that Scharpp was to have complete charge of Nazi activities from Valparaiso to Panama. That night they established Der Deutsch-Auslдndische Nazi Genossenschafts Bund, with the understanding that it function secretly. The list of members was to be controlled by Neumann. Scharpp explained that secrecy was advisable to avoid antagonizing the Panamanian Government, "which is friendly to Italy and we can cooperate with the Italian Legation here." "The Japanese are more important that the Italians," Kohpcke pointed out. "The Japanese will work with us," Heildelk assured him. "But we can't be seen with them—" "Fritz [Kohpcke] will call a meeting in Jacobs' house," said Scharpp. "Jacobs!" exclaimed one of the unidentified men. "You don't mean the Austrian Consul!" Scharpp nodded slowly. "He is generally believed to be anti-Nazi. His partner spent twelve years in Japan and speaks Japanese perfectly. The Japanese Consul knows and trusts both. We cannot find a better place." On the night of December 13, 1937, forty carefully selected Germans who, during the intervening month had become members of the Bund in Panama, arrived singly and in small groups [72]at the home of August Jacobs-Kantstein, Panamanian merchant and Austrian Honorary Consul. Five Japanese, headed by Tetsuo Umimoto, also came. One, K. Ishibashi, formerly captain of the "Hokkai Maru" and a reserve officer in the Japanese Navy; K. Ohihara, a Japanese agent staying with the Japanese Consul but having no visible reason to be in Panama; two captains of Japanese fishing boats and A. Sonada, the barber who organized the labor union and in whose presence the Consul does not sit until the barber is seated. Throughout the meeting, presided over by the elderly but tall and soldierly Austrian Consul, the Japanese said little. It was primarily the first get-together for Nazi-Japanese cooperation in the Canal Zone area. "Mr. Umimoto has not said much," remarked Jacobs. "There is so little to say when there are so many present," said the little Consul apologetically. The others understood. The Japanese were too shrewd to discuss detailed plans with so many present. A few days later Umimoto called upon Heildelk and was closeted with him for three hours. Shortly after that Sonada made a hurried trip to Japan.

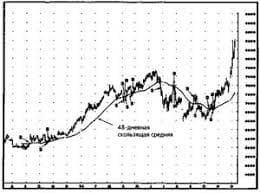

[73] VI   Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|