|

|

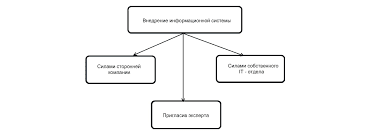

Conversational Implicature. IntroductionThe notion of conversational implicature is one of the single most important ideas in pragmatics (we shall often refer to the notion simply as implicature as a shorthand, although distinctions between this and other kinds of implicature will be introduced below). The salience of the concept in recent work in pragmatics is due to a number of sources. First, implicature stands as a paradigmatic example of the nature and power of pragmatic explanations of linguistic phenomena. The sources of this species of pragmatic inference can be shown to lie outside the organization of language, in some general principles for co-operative interaction, and yet these principles have a pervasive effect upon the structure of language. The concept of implicature, therefore, seems to offer some significant functional explanations of linguistic facts. A second important contribution made by the notion of implicature is that it provides some explicit account of how it is possible to mean (in some general sense) more than what is actually 'said' (i.e. more than what is literally expressed by the conventional sense of the linguistic expressions uttered). Consider, for example: 1. A: Can you tell me the time? B: Well, the milkman has come. All that we can reasonably expect a semantic theory to tell us about this minimal exchange is that there is at least one reading that we might paraphrase as follows: 2. A: Do you have the ability to tell me the time? B. [pragmatically interpreted particle] the milkman came at some time prior to the time of speaking. Yet it is clear to native speakers that what would ordinarily be communicated by such an exchange involves considerably more, along the lines of the italicized material in (3): 3. A: Do you have the ability to tell me the time of the present moment, as standardly indicated on a watch, and if so please do so tell me. B: No I don’t know the exact time of the present moment, but I can provide some information from which you may be able to deduce the approximate time, namely the milkman has come. Clearly the whole point of the exchange, namely a request for specific information and an attempt to provide as much of that information as possible, is not directly expressed in (2) at all; so the gap between what is literally said in (2) and what is conveyed in (3) is so substantial that we cannot expect a semantic theory to provide more than a small part of an account of how we communicate using language. The notion of implicature promises to bridge the gap, by giving some account of how at least large portions of the italicized material in (3) are effectively conveyed. Thirdly, the notion of implicature seems likely to effect substantial simplifications in both the structure and the content of semantic descriptions. For example, consider: 4. The lone ranger jumped on his horse and rode into the sunset. 5. The capital of France is Paris and the capital of England is London. 6.?? The lone ranger rode into the sunset and jumped on his horse. 7. The capital of England is London and the capital of France is Paris. The sense of and in (4) and (5) seems to be rather different: in (4) it seems to mean ‘and then’ and thus (6) is strange in that it is hard to imagine the reverse ordering of the two events. But in (5) there is no ‘and then’ sense; and here seems to mean just what the standard truth table for & would have it mean -namely that the whole is true just in case both conjuncts are true; hence the reversal of the conjuncts in (7) doesn't affect the conceptual import at all. Faced with examples like that, the semanticist has traditionally taken one of two tacks: he can either hold that there are two distinct senses of the word and, which is thus simply ambiguous, or he can claim the meanings of words are in general vague and protean and are influenced by collocational environments. If the semanticist takes the first tack, he soon finds himself in the business of adducing an apparently endless proliferation of senses of the simplest looking words. He might for example be led by (8) and (9) to suggest that white is ambiguous, for in (8) it seems to mean ‘only or wholly white’ while in (9) it can only mean ‘partially white’. 8. The flag is white. 9. The flag is white, red and blue. The semanticist who takes the other tack, that natural language senses are protean, sloppy and variable, is hardly in a better position: how do hearers then know (which they certainly do) just which variable value of white is involved in (8)? Nor will it do just to ignore the problem, for if one does one soon finds that one's semantics is self-contradictory. For example, (10) certainly seems to mean (11); but if we then build the ‘uncertainty’ interpretation in (11) into the meaning of possible, (12) should be an outright contradiction. But it is not. 10. It’s possible that there’s life on Mars. 11. It’s possible that there’s life on Mars and it is possible that there is no life on Mars. 12. It’s possible that there’s life on Mars, and.in fact it is certain that there is. Now from this set of dilemmas the notion of implicature offers a way out, for it allows one to claim that natural language expressions do tend to have simple, stable and unitary senses (in many cases anyway), but that this stable semantic core often has an unstable, context-specific pragmatic overlay - namely a set of implicatures. As long as some specific predictive content can be given to the notion of implicature, this is a genuine and substantial solution to the sorts of problems we have just illustrated. An important point to note is that this simplification of semantic is not just a reduction of problems in the lexicon; it also makes possible the adoption of a semantics built on simple logical principles. It does this by demonstrating that once pragmatic implications of the sort we shall call implicature are taken into account, the apparently radical differences between logic and natural language seem to fade away. We shall explore this below when we come to consider the ‘logical’ words in English, and, or, if... then, not, the quantifiers and the modals. Fourthly, implicature, or at least some closely related concept, seems to be simply essential if various basic facts about language are to be accounted for properly. For example, particles like well, anyway, by the way require some meaning specification in a theory of meaning just like all the other words in English; but when we come to consider what their meaning is, we shall find ourselves referring to the pragmatic mechanisms that produce implicatures. We shall also see that certain syntactic rules appear at least to be sensitive to implicature, and that implicature puts interesting constraints on what can be a possible lexical item in natural languages. Finally, the principles that generate implicatures have a very general explanatory power: a few basic principles provide explanations for a large array of apparently unrelated facts. For example, explanations will be offered below for why English has no lexical item nail meaning ‘not all’, for why Aristotle got his logics wrong, for ‘Moore’s paradox’, for why obvious tautologies like War is war can convey any conceptual import, for how metaphors work and many other phenomena besides.   Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|