|

|

IV. The Complexity of Written LanguageConsider the following fragments: A. The Arlington Reader is organized into ten thematic chapters on general interest topics. (Bloom L.Z., Smith L.Z. The Arlington Reader. N.Y.: Bedford/St. Martins, 2003, p. viii). B. The continuing emission of greenhouse gases would create protracted crop-destroying droughts in continental interiors. (Bloom L.Z., Smith L.Z. op.cit, p. xvi). C. Государство принимает участие в формировании доходов бюджетов местного самоуправления, финансово поддерживает местное самоуправление. Расходы органов местного самоуправления, возникшие вследствие органов государственной власти, компенсируются государством. (Земельный кодекс Украины. Харьков: Одиссей, 1998, с. 5). Fragment A consists of 13 words, 4 of them are grammatical, 9 are lexical. Fragment B is made of 15 words. Of these, 11 are lexical items (content words) and 4 are grammatical items (function words). Grammatical items are those that function in closed systems in the language: in English, determiners, pronouns, most prepositions, conjunctions, some classes of adverb, and finite verbs. (Determiners include the articles.) In example A, the grammatical words are the, is, into, on. In other words, there are twice as many lexical words as there are grammatical words. Compare this with the below fragment, taken from oral conversation: The only real accident that I've ever had was in fog and ice. Counting I’ve as one word, this has 13 words; of these, the, only, that, I've, ever, had, was, in, and and are grammatical items; the lexical Items are real, accident, fog, and ice. Here the proportions are reversed: twice as many grammatical as lexical. This is a characteristic difference between spoken and written language. Written language displays a much higher ratio of lexical items to total running words. This is not just a consequence of the subject-matter. Here is a ‘translation’ of fragment B into a spoken form. This is how the written statement was presented by its author when she was speaking at one of the environment meetings. Figures in brackets show the numbers of lexical (L) and grammatical (G) words. If we keep emitting green house gases then of course it would create droughts, most disastrous droughts, very long droughts which are sure to destroy all crops in our continental interiors. Yeah (L.: 13; G.: 17). Here are some more examples to illustrate written and spoken correspondencies. Figure 7.1 – Lexical and grammatical words frequency in written and oral statements

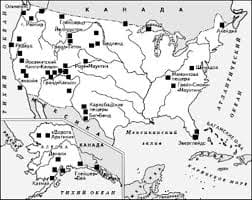

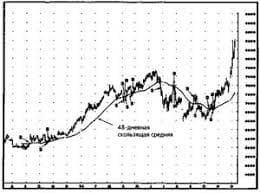

We can explain the significance of this distinction as follows. The difference between written and spoken language is one of density: the density with which the information is presented. Relative to each other, written language is dense, spoken language is sparse. A number of factors contribute to this density; it is a fairly complex phenomenon, as we would discover if we tried to quantify it in an exactway. But it is mainly the product of a small number of variables, andthese we can observe without a complicated battery of measurements. One caution should be given. By expressing the distinction in this way, we have already ‘loaded’ it semantically. To say that written language is ‘more dense’ is to suggest that, if we start from spoken language, then written language will be shown to be more complex. We could have looked at the same phenomenon from the other end. We could have said that the difference between spoken language and written language is one of intricacy, the intricacy with which the information is organised. Spoken language is more intricate than written. In the next chapter, we shall look into the phenomenon of intricacy – which is in fact a related phenomenon, but seen from the opposite perspective. From that point of view, it will appear that spoken language is more complex than written. The conclusion will be that each is complex in its own way. Written language displays one kind of complexity, spoken language another. Our aim will be to make clear what these are. After considering both kinds of complexity, we shall try to account for them under a single generalisation. This will relate to the concept of lexico-grammar: the level of ‘wording’ in language. One way of expressing the matter – rather oversimplified, but it provides a pointer in the right direction – that the complexity of written language is lexical, while that of spoken language is grammatical. What we are examining now, therefore, with the notion of ‘density’, is a kind of complexity that arises in the deployment of words. Lexical Density The distinction we have to recognise at this point is one we have referred to already: that between lexical items and grammatical items. Lexical items are often called ‘content words’. Technically, they are items (i.e. constituents of variable length) rather than words in the usual sense, because they may consist of more than one word: for example, stand up, take over, call off, and other phrasal verbs all function as single lexical items. They are lexical because they function in lexical sets not grammatical systems: that is to say, they enter into open not closed contrasts. A grammatical item enters into a closed system. For example, the personal pronoun him contrasts on one dimension with he, his; on another dimension with me, you, her, it, us, them, one; but that is all. There are no more items in these classes and we cannot add any. With a lexical item, however, we cannot close off its class membership; it enters into an open set, which is indefinitely extendable. So the word door is in contrast with gate and screen; also with window, wall, floor and ceiling; with knob, handle, panel, and sill; with room, house, hall; with entrance, opening, portal – there is no way of closing off the sets of items that it is related to, and new items can always come into the picture. As you would expect, there is a continuum from lexis into grammar: while many items in a language are clearly of one kind or the other, there are always likely to be intermediate cases. In English, prepositions and certain classes of adverb (for example, modal adverbs like always, Like many other features of language, the distinction is quite clear in our unconscious understanding (which is never troubled by borderline cases, unlike our conscious mind). Children are clearly well aware of it – one of the developmental strategies used by many children for constructing sentences in the mother tongue is to leave out all grammatical items; and some children re-use this strategy when first learning to write (see Mackay et al. 1998). We have already pointed out that the distinction is embodied in our spelling system, since grammatical items may have only one or two letters in them, whereas lexical items require a minimum of three (showing incidentally that prepositions, at least the common ones, belong to the ‘grammatical’ class, because of words like at, in, to, on, which otherwise would have to be spelt att, inn, too, onn). And there are some ‘special languages’ around the world that are based entirely on this distinction, since they require all lexical items to be altered while all grammatical ones remain unchanged – for example the mother-in-law language in Dyirbal, North Queensland (see Dixon 1980). So it is not surprising that the distinction is fundamental to the difference between speech and writing. In principle a grammatical item has no place in a dictionary. But our tradition of dictionary-making is to include all words, grammatical as well as lexical; so the dictionary solemnly enters the and it, even though it has nothing to say about them – nothing, that is, that falls within the scope of lexicology. A more consistent practice is that of Roget’s Thesaurus, which does leave out most of the grammatical words; those that are included are there because Roget treats them lexically, for example lining up me with personality, ego, spirit (and not with you and us). As a first approximation to a measure of lexical density, therefore, we can draw the distinction between lexical and grammatical items, simplifying it by treating each word (in the sense of what is treated as a word in the writing system, being written with a space on either side) as the relevant item, and counting the ratio of lexical to grammatical words. We then express this as a proportion of the total number of running words. If there are 12 lexical and 8 grammatical items, this gives the proportion of lexical items to the total as 12 out of 20, which we show as a lexical density of 60 per cent, or 0.6. In general, the more ‘written’ the language being used, the higher will be the proportion of lexical words to the total number of running words in the text. Frequency The next thing to take account of is probability. Another aspect of the distinction between lexical and grammatical words is that grammatical items tend to be considerably more frequent in occurrence. A list of the most frequently occurring words in the English language will always be headed by grammatical items like the and and and it. Lexical items are repeated much less often. This in itself is entirely predictable, and of no great significance to the present point. What is significant is the relative frequency of one lexical item to another. We have been assuming a simple measure in which all lexical items count the same. But the actual effect that we are responding to is one in which the relative frequency of the item plays a significant part. The relative frequency of grammatical items can be ignored, since all of them fall into the relatively frequent bracket. But the relative frequency of lexical items is an important factor in the situation. The vocabulary of every language includes a number of highly frequent words, often general terms for large classes of phenomena. Examples from English are thing, people, way, do, make, get, have, go, good, many. These are lexical items, but on the borderline of grammar; they often perform functions that are really grammatical – for example thing as a general noun (almost a pronoun) as in that’s a thing I could well do without; make as a general verb, as in you make me tired, it makes no difference. They therefore contribute very little to the lexical density. By contrast, a lexical item of rather low frequency in the language contributes a great deal. Clearly there is a difference between the following examples in the feeling of density that they give: compare · the mechanism of sex determination varies in different organisms · the way the sex is decided differs with different creatures or · different creatures have their sex decided in different ways. The proportion of lexical items is about the same in all three; but the last two ‘feel’ less dense because they include very frequent items such as have and way. Another factor that operates here is that the last two examples incorporate a repetition, the item differ/different. Repetition also reduces the effect of density – since even if a word is intrinsically rare, its occurrence sets up the expectation that it will occur again. Note that normally all the members of a morphological paradigm are the same lexical item: for example, differ, differed, different, difference, differing, differently are all instances of the one lexical item (but not differential in differential equation). This is another difference between ‘lexical item’ and ‘word’. For a systematic, formal investigation of lexical density in texts we should have to adopt some weighting whereby lexical items of lower frequency ‘scored’ more highly than common ones. Word-frequency lists have been available for some time, and there are now large bodies of written and spoken text in machine-readable form in various places from which such information can readily be obtained. But for immediate practical purposes, either all lexical items can be treated alike – this will still show up the difference between spoken and written texts – or a list can be drawn up of high-frequency lexical items to be given half of the value of the others. This is equivalent to recognising three categories rather than two: grammatical items, high-frequency lexical items, and low-frequency lexical items.   Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|