|

|

A more Revealing Measure of Lexical DensitySo far we have assumed that the feature of lexical density was just something to do with words. The measurements we have suggested have been concerned with the pattern of distribution of words of different kinds in spoken and written texts. We started with a classification of all words into two categories – grammatical and lexical – and envisaged the possibility of refining this by taking into account the frequency of a word in the language (i.e. its unconditioned probability of occurrence at any point) – either crudely, but enough to allow for the much greater effect of low-frequency lexical items, or more delicately by building in a differential system of weightings for all. However far we took such refinements, we should still be measuring words against words. But this is rather one-sided, because it suggests that spoken language is simply to be characterised by a negative feature, the relative absence of (or low level of) density of information. Is there any way of reinterpreting this notion so that it tells us something positive about spoken language as well? Let us examine the notion of density further. It has to do, as already suggested, with how closely packed the information is. This is why the probability of the item is important: a word of low probability carries more information. But words are not packed inside other words; they are packaged in larger grammatical units – sentences, and their component parts. It is this packaging into larger grammatical structures thatreally determines the informational density of a passage of text. Which is the most relevant of these larger structures? There is one that clearly stands out as the unit where meanings are organised and wrapped up together, and that is the clause. The clause is the grammatical unit in which semantic constructs of different kinds are brought together and integrated into a whole. This always appears a difficult notion at first, because of the inconsistency with which the terms ‘clause’ and ‘sentence’ are used in traditional grammars. But in fact it is not excessively complicated. If we take as our starting point the observation that a so-called ‘simple sentence’ is a sentence consisting of one clause, then much of the difficulty disappears. What is traditionally known as a ‘compound sentence’ will still consist of two or more clauses; and each of them potentially carries the same load of information as the single clause of a ‘simple sentence’. Eventually we shall discard the term ‘sentence’ from the grammar altogether; it can then be used unambiguously to refer to a unit of the writing system – that which extends from a capital letter following a full stop up to the next full stop. In place of ‘sentence’ in the grammar we shall use clause complex, because that will allow us to refer both to written and to spoken language in a way that makes the two comparable. We cannot identify a ‘sentence’ in the spoken language; or rather, we can identify a sentence in spoken language only by defining it as a clause complex. And since the notion of a ‘complex’ can be formally defined, and yields not only clause complexes but also phrase complexes, group complexes, and word complexes, it seems simpler to adopt this term throughout. The clause complex is, in fact, what the sentence (in writing) comes from. The unit that was intuitively recognised by our ancestors when they first introduced the ‘stop’ as a punctuation mark was the clause complex; that is, a sequence of clauses all structurally linked. For our notation, we will use three vertical strokes to mark a sentence boundary (still using the term ‘sentence’ pro tem; but gradually phasing it out), and two vertical strokes to mark a clause boundary. For example:

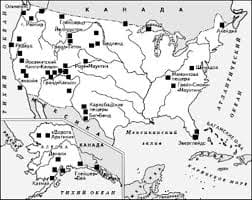

The basic ‘stuff’ of living organisms is protoplasm. There is no set composition of this || and it varies between one individual and the next. The clause is the gateway from the semantics to the grammar. It provides a more powerful and more relevant organising concept for measuring lexical density, and, more generally, for enabling us to capture the special properties of both spoken and written language. Instead of counting the number of lexical items as a ratio of the total number of running words, we will count the number of lexical items as a ratio of the total number of clauses. lexical density will be measured as the number of lexical items per clause. Keeping to the simplest classification (each word is either a lexical item or a grammatical item), the three clauses in the above text contain, respectively, five (basic, stuff, living, organisms, protoplasm), two (set, composition), and two (varies, individual) lexical items; a total of nine, giving an average of three per clause. We will therefore say that this text has a mean lexical density of 3.0. The Clause What we are measuring, then, for any text, spoken or written, is the average amount of lexical information per clause. No account need be taken, for purposes of this particular measurement, of the number and organisation of clauses in the sentence (clause complex). But it will be necessary to identify explicitly what is a clause. It is not always easy, however, to recognise what a clause is. Again, for comparative purposes, the main requirement is consistency; but since this category is perhaps the most fundamental category in the whole of linguistics, as well as being critical to the unity of spoken and written language, it is important to devote a section to the discussion of it. Precisely because it is so fundamental a category, the clause is also impossible to define; nor is there just one right way of describing it. Being so complex and many-sided, it lends itself to different theoretical interpretations; there are very many different kinds of generalisation that a linguist may be interested in, for different purposes, and the clause is likely to come out looking somewhat different in each case. But all interpretations will also have something in common. The brief outline, given below represents an interpretation that has been found useful in the general context of educational linguistics. It is a theoretical interpretation with a strongly pragmatic motive behind it, derived from two complementary aspects of experience – that theories are developed for the purpose of being applied, but that unless you develop a theory you will not have anything to apply. The principal purposes for which this interpretation has been used are text analysis, from natural conversation to literature; the study of functional variation (register) in language; language teaching, including mother tongue and foreign language; child language development; and artificial intelligence research. According to this interpretation, the clause is a functional unit with a triple construction of meaning: it functions simultaneously (l) as the representation of the phenomena of experience, as these are interpreted by the members of the culture; (2) as the expression of speech function, through the categories of mood and (3) as the bearer of the message, which is organised in the form of theme plus exposition. To each of these functions corresponds a structural configuration, (1) in terms of a process (action, event, behaviour, mental process, verbal process, existence, or relation) together with participants in the process and circumstances attendant on it (‘Medium’, Agent, Beneficiary, Time, Cause, etc.); (2) in terms of an element embodying an arguable proposition (Subject plus Finite) and residual elements (Predicator, Complement, and Adjunct); (3) in terms of a thematic element, given prominence as what the message is about, and a residual element summarised as the ‘Rheme’). In addition, (4) the clause provides a reference point for the information structure in spoken discourse, closely related to (3) – there is systematic interplay between the Theme – Rheme organisation of the clause and the Given – New organisation of the information unit (realised as a tone group) (for details see Halliday 1985, 2000). An example of the analysis of a clause in these terms is given in Figure 7.2   Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|