|

|

Figure 7.5 – Structure of a nominal groupPremodifier Head Postmodifier

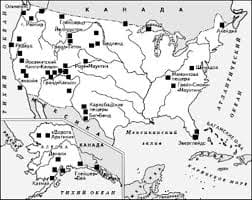

In addition to the Head noun, which represents the ‘Thing’ – the class of phenomena being referred to – there are other functions, those of Classifier and Epithet, which also contain lexical information: the subclass (electric trains as opposed to steam or diesel) and qualities of various kinds (for example, old), including those expressing the speaker’s attitude (for example, splendid). All these are present without embedding; if in addition we add down-ranked prepositional phrases and clauses, as Qualifiers, then each of these opens up the possibility of further nominal groups, which in turn may contain Epithets, or Classifiers; and so forth. Verbal groups, on the other hand, contain only one lexical element: the verb itself. Other lexical material may be expressed in adverbial groups; but these are very limited in scope. About the only nominal group in these clauses that could have been replaced by an adverbial group is (with) uniform velocity, where we might have had steadily fast; but it is not very easy – all the expressions usually used in this general sense encode ‘fast’ as a noun and ‘steadily’ as an adjective: (with) uniform velocity, (at) constant speed, (at) a steady pace, and so on. Thus there are a lot of things that can only be said in nominal constructions; especially in registers that have to do with the world of science and technology, where things, and the ideas behind them, are multiplying and proliferating all the time. That is to say; they can only be said this way in the grammar of modern English. The question whether the grammar had to evolve this way in order to say them is a fundamental issue that, regretfully, would require a whole further treatise to itself. And even then we would not find the answer. The Structure of the Clause As far as the structure of the clause is concerned, there is another source of pressure towards nominalisation. This has to do with the category of theme, which was referred to briefly above. In addition to its organisation as representation of a process (transitivity) and as bearer of a speech function (mood), every clause is also structured as a message. It consists of two parts: a Theme, which is the point of departure – what the message is about; and another element that constitutes the body of the message, known as the Rheme. In some languages there are special particles for indicating what is the Theme. In English, the message structure is expressed by word order: the Theme comes first. The Theme itself can be a fairly complex structure, but what concerns us here is the topical element within it – the portion that functions in transitivity. In the examples above, the topical component of the Theme is (1) in the Newtonian system, (2) our apparent imaginative understanding of these processes, and (3) he. The Theme is an important part of the message, since it is here that the speaker announces his intentions: the peg on which the message is to hang. In spoken language it is often a pronoun, most typically I or you. But in writing, with its more strongly ‘third person’ orientation, it is usually some other phenomenon; and again this is typically a nominal element. It cannot, except in special circumstances, be a verbal group; so this is another reason why lexical material tends to be packaged in nouns. It can be a prepositional phrase, as in (1) above; but here, as we have already seen, the content is in the nominal group that is embedded inside it. It can be an adverbial group; but these, as has been observed, have a fairly limited semantic scope. Furthermore, there is a special structure in English that has evolved as a means of packaging the message in the desired thematic form. These are what in formal grammars are called ‘cleft’ and ‘pseudo-cleft’ constructions. Consider the clause (made up for purposes of the discussion) the force of gravity attracts the planets to the sun. Let us suppose, now, that we want to vary this message in different ways. There are many possibilities; we will illustrate two. 1. Suppose we want the force of gravity to be the focus of information, the New element in the information structure. If we were saying this, we could say it as //1 ‸ the / force of / gravity at/tracts the / planets to the / sun // In writing we cannot do this; instead we assume an unmarked information structure, with the New at the end, and write · The planets are attracted to the sun by the force of gravity. This will now be ‘read’ with the focus on gravity. However, we have now disturbed the thematic structure; instead of the force of gravity being Theme, the Theme is now the planets. If the writer wants to have the force of gravity both as Theme and as New ('this is what I'm talking about – and it’s also what I want you particularly to attend to'), he introduces a special structural device for predicating the Theme: · It is the force of gravity that attracts the planets to the sun. This puts the tonic back on gravity. 2. Suppose on the other hand that the writer (or speaker, in this case; here both will need a resource for the purpose) wants to have, not just the planets as Theme but the whole of the planets are attracted to the sun: ‘I want to tell you about planet-to-sun attraction’. The only way of achieving this is to package all of these up together: · What attracts the planets to the sun is the force of gravity. This has the effect of making the whole of what attracts the planets to the sun into the Theme, and then identifying this Theme, by means of the verb be, with the force of gravity as Rheme. Let us set these out with the structural notation: (a) || it | is | the force of gravity | [[ that attracts the planets to the sun ]] || (b) || [[ what attracts the planets to the sun ]] | is | the force of gravity || In (b), what attracts the planets to the sun is both Theme and Subject. In (a), the Subject is again it... that attracts the planets to the sun; but the Theme is the force of gravity. This is what is known as a ‘marked’ Theme: one that has special prominence precisely because it is not the Subject. In both these cases, the writer has depended on nominalisation to get the meaning he wants. In other words, even things that are not expressed as nouns have to behave like nouns in order to gain their appropriate status in the thematic and information structure. This is the second of the kinds of pressure that tend towards nominalised forms of expression in English. In order to exploit the full potential of the language for mapping any transitivity structure – any configuration of process, participants, and circumstances – on to any desired message structure (Theme and Rheme, Given and New, in all their possible combinations), one has to be prepared to express oneself in a nominalised form. So the structure of the modern world and the structure of the language combine together to make the written language what it is: a language with a high lexical density, measured in the number (and informational load) of lexical items per clause, and a strong tendency to encode this lexical content in a nominal form: in head nouns, other items (nouns and adjectives) in the nominal group, and nominalised clauses. It is these nominal structures that give the clause its enormous elasticity. This is not to say they are never overused: it is always possible to overdo a good thing. But it is important, if one is critical of such tendencies, to understand how the patterns in question are functional in the language. V. Further Reading From: S. Johansson. The Three Major Word Classes // Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. L. Longman, 1999. P. 55-57.   ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|