|

|

The Myth of the Drying Phase

One of my personal peeves when discussing roasting is the use of the misleading terms “drying phase” and “development time.” Roasting is a complex process in which development and moisture loss, among other changes, occur continuously throughout a batch. The practice of referring to the first phase of roasting as the “drying phase” and the last stage as “development time” has led to much misunderstanding of the roasting process.

The Middle (Nameless) Phase

At a few minutes into a roast, once the beans have turned a shade of tan or light brown, begins the neglected, nameless, middle phase. During this phase sugars break down to form acids19 and the beans release steam, begin to expand, and emit pleasant, bready aromas. The changes in color and aroma are largely the work of Maillard reactions, which accelerate as bean temperatures reach approximately 250°F-300°F (121°C-149°C).

At approximately 340°F (171°C), caramelization begins, which degrades sugars, thus slowing the Maillard reactions by stealing their fuel. Caramelization deepens the beans’ brown color and creates fruity, caramelly, and nutty aromas. Both Maillard reactions and caramelization decrease coffee’s sweetness and increase bitterness.

During this (nameless) phase, expansion of the beans causes them to shed their chaff, or silver skin. Simultaneously, smoke develops, and the machine operator must ensure the airflow is high enough to exhaust the chaff and smoke as it forms. Inadequate airflow at this stage may lead to smoky-flavored coffee and could create a fire hazard if chaff builds up excessively in certain areas of the roaster.

First Crack

While the process of roasting beans can be monotonous at times, first crack is always exciting. The bean pile emits a series of popping noises that begins quietly, accelerates, reaches a crescendo, and then tapers. The beans spontaneously expand and expel chaff, and smoke development intensifies. As noted earlier, first crack represents the audible release of pent-up water vapor and CO2 pressure from the bean core.

According to Illy5 and Eggers,30 bean surface temperatures decrease for a brief period (probably several seconds, though your bean probe will likely not indicate this change), a phenomenon known as the endothermic flash. The flash is due to the surface-cooling effect of evaporation as large amounts of water vapor escape the beans.

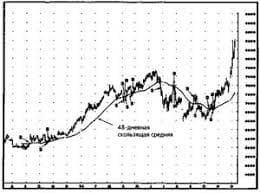

Shortly before first crack, the bean-pile temperature’s rate of rise (ROR) is prone to level off. It tends to plummet at around the time of the endothermic flash and will often accelerate rapidly after the flash. These shifts in the ROR are undesirable, and I discuss them in depth later in this book. (See “The Bean Temperature Progression Shalt Always Decelerate” in Chapter 10.)

Acidity increases during roasting until the beans reach a city roast and declines with further roasting. Aromatics peak shortly afterward, in the range of city to full city roast. Body increases until a roast reaches a very dark color somewhere in the vicinity of French roast, after which body declines. Extraction potential is maximized at a French roast and decreases thereafter as pyrolysis burns off soluble mass.

Second Crack

After the completion of first crack there is a quiet lull during which CO2 pressure builds anew in the bean core. The pressure is able to force oils to the bean surface because pyrolysis and the trauma of first crack have weakened the bean’s cellulose structure. Right around the time the first beads of oil appear on bean surfaces, second crack begins, releasing CO2 pressure and oils from the inner bean.

Roasting into second crack destroys much of a coffee’s unique character because caramelization and pyrolysis yield heavy, pungent, and roasty flavors that overwhelm whatever subtle flavors survive such dark roasting. In the cup, dark roasts exhibit bittersweet and smoky flavors; heavy, syrupy body; and minimal acidity. If roasting is taken much further than early second crack, then burnt, carbonized flavors appear and body declines. While perhaps the majority of specialty coffee chains roast into second crack, today’s progressive specialty roasters rarely do.

It is vital to understand that the shape of the entire roast curve influences bean development.

Development Time

Many roasters refer to the time from the onset of first crack until discharging the beans as “development time.” This is a misleading term that oversimplifies the roasting process. As shown in the graph “Inner Vs. Outer Bean Temperature,” in Chapter 6, after the first several seconds a batch is in the roaster, inner-bean development occurs continually until the end of the roast. Roasters often attempt to improve development, especially in roasts for espresso, by lengthening the roast time after first crack. Extending the roast time after first crack will usually increase development of the bean core, but the more efficient way to improve inner-bean development is to create a larger temperature gradient earlier in the roast. Intentionally extending the last few minutes of a roast usually creates baked flavors and should be avoided.

It is vital to understand that the shape of the entire roast curve influences bean development and moisture loss. In Chapter 10, “The Three Commandments of Roasting,” I discuss how to shape the roast curve to enhance bean development and sweetness while eliminating the risk of creating baked flavors. Planning a Roast Batch

A roaster must make many decisions before charging a batch of coffee. He must consider batch size, machine design, and various bean characteristics before choosing the charge temperature, initial gas setting, and airflow.

Batch Size

The first step when planning a roast is to determine a machine’s optimal range of batch sizes. One must consider a machine’s drum size, airflow range, and rated burner output to decide what batch sizes will taste best. One should not assume that a roaster’s stated capacity is its optimal batch size; I have found that many, if not most, machines produce the best coffee at 50%-70% of their nominal capacity.

Roasting machine manufacturers are motivated to exaggerate their machines’ capacities because most buyers, especially of small, specialty machines, are influenced by that headline number.* One can estimate a machine’s realistic maximum batch size by first noting the machine’s stated capacity. That number most likely represents the largest batch a roaster should attempt to put into that machine’s drum. Filling a drum past its stated capacity may lead to less effective mixing of beans during roasting or to the exhaust fan sucking beans out of the roaster.

Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|