|

|

Roasting, Brewing, and Extraction

How dark should you roast? I can’t answer that question for you, but if you master roast development and coffee extraction, you might find that your preferred roast degree gets lighter. Inadequate development and extraction often yield sharp- or sour-tasting coffee, causing roasters to roast darker to tone down those qualities. Darker roasting will diminish these undesirable flavors, but it will also decrease sweetness and aroma while increasing weight loss. The goal of this chapter is to help roasters roast lighter, if they desire to, by learning to identify development and extraction problems.

Testing Roast Development

The lighter one roasts, the more challenging it is to fully develop the bean centers. When a roaster has difficulty developing a coffee, he will often choose to roast darker to improve the odds of good development. Ideally, when struggling with development, a roaster should figure out how to increase development at the desired roast degree, not roast darker to cover up inadequate development.*

If you would like to test and calibrate your roast development, especially if you are not regularly extracting above 19% with ease, consider purchasing a “control” coffee that is definitely well developed. I recommend against buying a lightly roasted coffee from one of today’s popular third-wave roasters as your control, as few of them fully develop their coffee with consistency. Instead, I recommend using a trick I learned from Vince Fedele of VST Inc, inventor of the coffee refractometer: Buy a light-to-medium roast from Illy. Illy’s choice of green coffee or roast may not match your taste, but you can be assured of fully developed beans. (If you’d like other suggestions for obtaining fully developed roasts, feel free to email me at scottrao@gmail.com.) Your coffee’s extractions should approximate those of the control coffee, although some well-developed, very light roasts may extract a percentage point or so lower than the control beans.

Calibrating Extraction

Much as poor development may lead one to roast darker, habitual underextraction may also influence a roaster’s choice of roast degree. Underextraction often produces sour-tasting coffee, especially when the beans are brewed as espresso. Roasters who don’t realize they are underextracting often try to decrease acidity by roasting darker or extending the roast time after first crack, baking their coffee along the way. These roasters will produce better coffee if they ensure they are judging roasts brewed at proper extractions levels. I recommend measuring your extractions frequently with a refractometer to be certain you are evaluating roasts at your grinder’s optimal extraction level. Ideal extractions for most brewing methods are usually in the range of 19%-22%, depending on the grinder and the sharpness of its burrs. Please see my ebook Espresso Extraction: Measurement and Mastery (available from all Amazon.com websites) for an in-depth discussion of this topic.

As a practical benchmark, aim for a minimum extraction of 19.5% when brewing espresso with a 50%, or 1:2, brewing ratio (i.e., the dry dose is half of the shot weight). For example, if you use 18 g of grounds to produce a 36 g shot, the extraction should be 19.5% or higher.

If your roasts do not regularly yield 19.5% when you use a 1:2 brewing ratio, first ensure that your roast development is adequate (ideally, by comparing your coffee’s extractions with those of a control coffee). If you are confident in the roast development, then inappropriate brewing-water chemistry, low grind quality, or poor brewing technique may be limiting extraction. Substandard brewing water, such as water that has very high total dissolved solids (TDS) or hard water that has been artificially softened, may limit extraction because it is a poor solvent. Low grind quality, usually due to small or dull burrs, may produce too many fines and boulders, which also decreases extraction. If you find that your extractions are inconsistent, even when pulling shots from the same roast batch, improper technique is probably hindering you.

I’ve had some amazing espresso in Andy’s kitchen.

Roasting for Espresso

Most roasters roast their espresso blends darker than their other coffees. That’s understandable, given that the vast majority of espresso shots end up in milky drinks. Most light roasts either don’t have the heft to balance several ounces of milk or they are too acidic to complement the flavor of milk. Other than potentially roasting darker, particularly for shots intended for milk-based drinks, I do not think roasters should make any other adjustments when roasting for espresso.

The goal when roasting for any brewing method should be to create the desired balance of sweetness and acidity while maximizing development. If a roaster follows the roasting recommendations in this book and extracts espresso properly, he will likely find that his preferred roast for straight espresso (i.e., served without milk) is identical, or nearly so, to his chosen roast for filter coffee and other brewing methods.

As noted in the previous section, poor development and underextraction often have undue influences on roasting decisions. In the case of espresso, during the two decades before the arrival of the coffee refractometer, two concurrent trends in specialty coffee conspired to decrease development and extraction: lighter roasting and ristretto espresso. As the more progressive roasters adopted lighter roasting styles, underdevelopment became rampant. Simultaneously, underextraction became the norm with the rising popularity of ristretto-style espresso in third-wave shops.**

The coffee refractometer has provided roasters and baristi with an objective measurement of their extractions and has all but eliminated the third-wave obsession with underextracted ristretto shots. The next step is for roasters to improve their understanding of how to develop roasts efficiently. My hope is that the information in this book, especially Chapter 10, “The Three Commandments of Roasting,” helps roasters improve their bean development.

Blending

While the current trend is to serve single-origin coffee, the historical norm has been to brew blends of various beans. Blending allows a roaster to create a unique flavor profile that does not exist in any one bean. Alternatively, blending also enables a roaster to offer a more consistent flavor profile throughout the year; substitute coffees as needed based on cost, availability, or flavor; and invest in the marketing of a blend’s name. Proponents argue that blending provides consistency, while skeptics see it as a way for roasters to save money or mislead consumers. For example, coffee labeled “Kona blend” may legally contain only 10% of beans from Kona.

Inconsistent roasting, continual changes in green coffee’s quality and flavor throughout the year, and variations in harvest quality make blending inherently challenging. Simply put, there are too many moving parts to blend by formula. I recommend blending based on taste but acknowledge that results will never be perfectly consistent.

Roasters often debate the merits of blending before roasting (known as “pre-blending”) versus blending after roasting (“post-blending”). I believe that both methods can produce excellent results if done properly, though I personally prefer post-blending by taste.

I recommend the following procedure for post-blending:

1. Set up a cupping of all potential blend components, using relatively large samples. Brew with a ratio of perhaps 20 g of grounds to 320 g of water.

2. Spoon portions of each brewed component into an empty cup in the ratio you’d like to test. For example, to test a blend of three equal components, put 1 spoonful of liquid from each brew into the blending cup. For a 50/25/25 blend, use 2 spoonfuls of the first component and 1 spoonful each of the other components. 3. Taste the blend and repeat the process, adjusting the ratio of spoonfuls as you go.

4. Once you’ve settled on a blend, brew it as you normally would to confirm the results from the cupping table.

If you choose to pre-blend, I recommend meeting all of the following criteria to ensure good results:

Blend the green coffees a few days before roasting to equilibrate their moisture contents. Use only beans of very similar size and density.

Use only beans of the same processing type (for example, either washed or natural).

* I don’t advocate roasting lightly for its own sake. Until a roaster figures out how to fully develop beans at a particular roast degree, he should roast a little darker to ensure good development. I believe a caramelly medium roast is preferable to a sour, vegetal, underdeveloped light roast.

** Two notable exceptions are Nordic roasters, who have always roasted lightly, generally with skill, and Italian roasters, who have always roasted a little darker and extracted to reasonable levels. Those two groups largely avoided following the dual trends of underextracting and underdeveloping. Storing Roasted Coffee

Freshly roasted coffee contains approximately 2% carbon dioxide and other gases by weight. Pressure within the beans causes the gases to desorb (i.e., to be released) slowly, over many weeks’ time after roasting. During the first 12 hours or so after roasting, the internal bean pressure is high enough to prevent significant amounts of oxygen from entering a bean’s structure. Thereafter, oxidation causes staling of the coffee and degradation of its flavor.

A bean’s gas content, internal pressure, and rate of outgassing are all affected by the roast method. Roasting hotter or darker produces more gas, greater internal bean pressure, and a more expanded cell structure, with larger pores. These factors lead to faster gas desorption and accelerated staling after roasting. While I don’t think one should change roasting styles simply to increase roasted coffee’s shelf life, it’s useful to understand that darker roasts degas and stale more quickly than lighter roasts.

Roast development also affects the rate of degassing. If a bean is underdeveloped, parts of its cellulose structure will remain tough and nonporous, trapping gases in its inner chambers. A noticeable lack of outgassing in bagged, roasted coffee may indicate underdevelopment.

Several options exist for storing roasted beans, and each has unique pros and cons:

Unsealed containers

Valve bags

Unsealed containers: Beans stored in an unsealed bag or other air-filled container (such as a bucketwith a lid) stale quickly. Ideally, consume such coffee within 2-3 days of roasting.

Valve bags: Bags with one-way valves are the standard in the specialty-coffee industry. Such bagsallow gas to escape but generally prevent new air from entering. Coffee held in such bags will taste fresh for a couple of weeks. The most noticeable change in the coffee after a few weeks in a valve bag is loss of carbon dioxide and aroma. The CO2 loss will be especially noticeable during espresso extraction as a lack of crema.

Vacuum-sealed valve bags: Vacuum sealing greatly limits oxidation of coffee in a valve bag, slowingits flavor degradation.

An upstart roastery’s coffee in a valve bag

Nitrogen-flushed valve bags: Flushing a valve bag with nitrogen decreases potential oxidation toalmost nil. Valve bagging limits coffee’s oxidation but has minimal effect on the loss of internal, pressurized gases. Upon opening a valve bag after several days or weeks of storage, the beans stale much faster than fresh, just-roasted coffee would, because they lack gas pressure to repel oxygen. For example, coffee stored in a valve bag for 1 week will taste fresh upon opening the bag but within a day will degrade almost as much as it would have had it spent the week in an unsealed bag.

Airtight bags: Few roasters use airtight bags anymore. Such bags limit oxidation, but bean outgassingcauses the bags to puff up, making their storage and handling inconvenient.

Nitrogen-flushed, pressurized containers: This is the most effective packaging option. Nitrogenflushing prevents oxidation, and pressurizing the container (usually a can) prevents outgassing. Storing the container at a cool temperature (the cooler, the better) slows staling, allowing a coffee to taste fresh for months after roasting.

Freezing: Although it still has its skeptics, freezing has proven itself to be very effective for long-term coffee storage. Freezing decreases oxidation rates by more than 90% and slows the movement of volatiles.34 There is no need to worry about the moisture in freshly roasted coffee actually freezing, as it is bound to the cellulose matrix, which makes it nonfreezable.35 The best way to freeze beans is to put a single serving (whether for a pot or a cup) into an airtight package, such as a Ziploc® bag. Remove the package from the freezer and allow the beans to warm to room temperature before opening the package and grinding the beans. Choosing Machinery

Selecting a roasting machine is a long-term commitment, and I hope readers do their homework before buying a machine. Most small roasters, especially first-time buyers, don’t have the experience to evaluate machines properly, so if that’s you, I recommend seeking expert advice before making what is probably your company’s largest investment. You must choose carefully because the majority of machines on the market today will limit your coffee’s quality or consistency, though their sales representatives may neglect to tell you that.

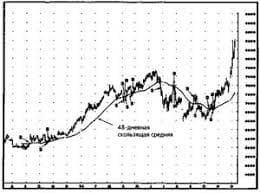

Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|