|

|

The Role of Icons in Orthodox Piety.Стр 1 из 23Следующая ⇒ A ny Western observer of an Orthodox service will immediately notice the special importance the pictures of saints have for the Orthodox believer. The Orthodox believer who enters his church to attend services first goes up to the iconostasis, the wall of paintings which separates the sanctuary from the nave. There he kisses the icons in a definite order: first the Christ icons, then the Mary icons, then the icons of the angels and saints. After this he goes up to a lectern — analogion — placed in front of the iconostasis. On this lectern the icon of the saint for the particular day or the particular church feast is displayed. Here, too, he pays his respects by a kiss, bow and crossing himself. Then having expressed his veneration for the icons, he steps back and rejoins the congregation. This veneration of icons takes place not only in the church, but also at home. Every Orthodox family has an icon hanging in the eastern corner of the living room and bedroom, the so-called “beautiful” corner. It is customary for a guest, upon entering a room, to greet the icons first by crossing himself and bowing. Only then does he greet his host. To apprehend the special significance of the saint's image in the Eastern Orthodox Church we must consider the iconoclastic struggle. The anti-image movement was as passionate as the campaign later to be led by Luther and Calvin for purifying and reforming the western branch of the Catholic Church. During the eighth and ninth centuries — partly through the influence of Islamic rationalism — opposition to images began to pervade the Byzantine Church, led chiefly by a number of rationalistic Byzantine emperors (Leo III, the Isaurian, 716-41; Constantine V Copronymus, 741-75; Leo IV, 775-80; Leo V, the Armenian, 813-20; Theophilus, 829-42). This attack upon the sacred images shook the whole of Orthodox Christendom to its foundations. Although the instruments of political power were in the hands of the iconoclasts, who upheld their cause by burning images, by exiling and imprisoning the opposite party, their point of view was not victorious. The struggle ended ultimately in the reestablishment of the veneration of images. The “Feast of Orthodoxy,” which the entire Orthodox Church celebrates annually, was instituted in the year 842 to honor the victory of the iconophiles and the Church's official restoration of image-veneration under the Empress Theodora.

The “Strangeness” of Icons. T he Western observer will be struck by the style of these icons, as well as by the reverence shown to them. They have a curious archaic strangeness which partly fascinates, partly repels him. This strangeness is not easy to describe. When we of the West admire a painting, we admire it as the creative achievement of a particular artist. This is true even of religious art. A Madonna by Raphael is to us first of all a creative work of Raphael. Although sacred persons such as Christ, Mary, or the apostles are for the most part represented according to traditional concepts, the individual painter is concerned with giving the picture his personal stamp, and displaying his creative imagination. The painting of the Eastern Church, on the other hand, lacks precisely this element of free creative imagination which we prize. Centuries and centuries have passed in which the painters of the Eastern Church have been content to repeat certain types of sacred images. We do, of course, find certain variations between centuries and between the styles of different countries; but when we set these against the enormous range of style within the art of the Western Church, the deviations appear very slight, sometimes barely discernible. It is usually impossible for anyone but a specialist to assign an icon of the Eastern Church to any specific century. Knowledge of the art of the West is no help at all. For the art of the Eastern Church has nothing corresponding to the various styles into which the course of Western art can be divided, such as Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance. Thus, since we take our own standards for granted, we are apt to try to judge icon painting by our Western conceptions of religious art. We will then come to highly negative conclusions; we may decide that the ecclesiastical art of the Eastern Orthodox Church entirely lacks creative originality, or that its attachment to tradition is a sign of artistic incompetence. We must, however, cast aside such preconceptions and try to see these icons in the framework of their own culture. The Eastern Church takes quite another view of the role of the individual artist. Most of the Orthodox ecclesiastical painters have remained anonymous. Moreover, an icon painting is not the work of an “artist,” as we understand the word. Rather, the making of icons is a sacred craft and is practiced in monasteries that have won a reputation for this work. Each monastery represents a certain school. But these schools are not built around some outstanding painter who has communicated a new creative impulse to his disciples. Rather, the school is based on a tradition that is carefully preserved and passed on from one generation of monks to the next. Icons are often group products, each monk attending to his own specialty. One paints the eyes, another the hair, a third the hands, a fourth the robes, so that even in the productive process itself the factor of creative, artistic individuality is eliminated. In order to understand the painting of the Eastern Church the Occidental observer must make a certain effort of will; he must stop comparing icons to Western forms of painting and attempt to grasp the peculiar nature of Eastern icon making in terms of its theological justifications. To do this, he must be clear about certain fundamental matters.

The Dogmatic Nature of Icons. T he art of icon painting cannot be separated from the ecclesiastical and liturgical functions of the icons. Many Orthodox believers consider it sheer blasphemy to exhibit icons in a museum. To them this is a profanation. For the icon is a sacred image, a consecrated thing. This fact is present from the beginning, even as the icon is made. The procedure of painting itself is a liturgical act, with a high degree of holiness and sanctification demanded of the painter. The painter-monks prepare themselves for their task by fasting and penances. Brushes, wood, paints, and all the other necessary materials are consecrated before they are used. All this only confirms the theory that the sacred image has a specific spiritual function within the Eastern Orthodox Church, and that its tradition-bound form springs not from any lack of skill but from specific theological and religious conceptions which prohibit any alteration of the picture.

The Theology of Icons. D uring the eighth and ninth centuries, when the great battle over the icons was raging, the Fathers of the Byzantine Church wrote quantities of tracts in defense of sacred images. A glance at this literature is most instructive. Thus we see that from the very first the Orthodox theologians did not interpret icons as products of the creative imagination of a human artist. They did not consider them works of men at all. Rather, they regarded them as manifestations of the heavenly archetypes. Icons, in their view, were a kind of window between the earthly and the celestial worlds — a window through which the inhabitants of the celestial world looked down into ours and on which the true features of the heavenly archetypes were imprinted two-dimensionally. The countenance of Christ, of the Blessed Virgin, or of a saint on the icons was therefore a true epiphany, a self-made imprint of the celestial archetypes. Through the icons the heavenly beings manifested themselves to the congregation and united with it. Several iconologists of the eighth and ninth centuries developed this conception into the idea of incarnation: in the icon Christ becomes incarnate in the very materials, that is, in wood, plaster, egg white and oil, just as he incarnated in flesh and blood when he became a man. This idea never gained acceptance as Orthodox dogma. Nevertheless Orthodox theology does teach that the icons reproduce the archetypes of the sacred figures in the celestial world. Along with this goes an express prohibition against three-dimensional images of the saints. The celestial figures manifest themselves exclusively upon the mirror surface or window surface of the icon. The golden background of the icon represents the heavenly aura that surrounds the saints. To look through the window of the icon is to look straight into the celestial world. The two-dimensionality of the icon, therefore, and its golden nimbus are intimately bound up with its sacred character.

5. The Icon “Not Made by Hands.” T his conception of the icon as epiphany or “appearance” is fundamentally strange to us. We may approach an understanding of it if we bear in mind that many icons of the Eastern Church, especially the icons of Christ himself, are traditionally ascribed to archetypes “not made by hands.” These are pictures that appeared by some miracle — as, for example, the picture Christ left of himself when, according to an ancient legend of the Church, he sent to King Abgar of Edessa the linen cloth with which he had dried his face, upon which his portrait was impressed. This cloth with its picture “not made by hands” afterward worked many miracles. Other Christ icons are attributed to Luke, the painter among the apostles, who is credited by Orthodox tradition with having painted the first portraits of Jesus in his embodiment as man. Numerous icons of Mary also “appeared” in miraculous fashion: either the Blessed Virgin personally appeared in a church and left her picture behind as visible proof of the genuineness of her appearance or else an icon “painted itself” miraculously. A favorite legend of the Eastern Church is that of the holy icon painter Alypios, who attained to such holiness by his praying and fasting that the saints themselves took over the work of painting for him and miraculously limned themselves on the wooden tablets that he had prepared for painting. Much of the legend consists of stories describing how the painter is prevented from painting by illness or the malice of enemies. But on the day that the commissioned icon is supposed to be ready, it is found finished “of its own accord,” even though the painter had been physically unable to work on it. The saint who was to be represented on the icon suddenly appears, surrounded with wonderful light, steps into the empty surface of the wood and leaves behind his “authentic” image. A supernatural light long continues to emanate from the icon, thus confirming the miraculous personal entrance of the archetype into the image. Only by keeping this idea constantly in mind will we be able to grasp the special nature of Eastern Orthodox icon painting. Its repetitive quality was not due to a deficiency of artistic imagination. By the very nature of the icon, any intervention of human imagination is excluded. To change an icon would be to distort the archetype, and any alteration of a celestial archetype would be heretical in the same sense as a willful alteration of ecclesiastical dogma.

Icon and Liturgy. T he direct relationship between icon and liturgy is of crucial importance. Orthodox liturgy reaches its height in the celebration of the Eucharist. Orthodox doctrine holds that in the Eucharist the congregation experiences the manifestation of Christ, the foretaste of parousia, the Second Coming of Christ in glory. What is more, in the Eucharist there takes place the meeting of the entire congregation of heaven with the earthly congregation. Within the sanctified space of the church, heaven descends upon earth when the Eucharist is celebrated. Christ enters as triumphant Lord, surrounded by choirs of cherubim and seraphim, “borne upon the spears of the Heavenly Hosts,” as the liturgy puts it. The images in the church represent this epiphany. In view of this, it becomes important that the holy images have their fixed places within the church. To each spot inside the church certain icons are assigned; above all, the sanctuary, the iconostasis and the dome are adorned. For example, the icons of the two saints who originated the two Eucharistic liturgies employed in the Eastern Church — St. John Chrysostom and St. Basil — belong in the prothesis, 2 the chapel to the left of the altar where the Eucharistic elements are prepared. The special meaning of the arrangement is even plainer on the screen, the iconostasis. To begin with, the iconostasis was a simple, low barrier that separated the sanctuary from the rest of the church. In the course of the centuries, however, and under the influence of iconography, it grew higher and higher until it became a wall completely separating sanctuary from nave. This wall permits communication between the priest at the altar and the congregation only through three doors: the middle or royal door, a door on the right (south) and one on the left (north). The icons are not scattered over the iconostasis, but arranged in a fixed order. For example, the icon of Christ is always to the right, beside the royal central door; to its left is the icon of the Mother of God; to the right of Christ, the icon of John the Baptist, and to the left of Mary, the icon of the saint to whom the church is dedicated. The archangels Gabriel and Michael are usually to be found on the door itself, as representatives of the highest choirs of the heavenly host. These are the principal icons and are usually life-size. Above them hang three or four rows of smaller icons — their number depending on the size of the church — in which the whole story of redemption and the hierarchy of the celestial Church are represented. The usual order is as follows: first a row of apostles, then a row of saints and martyrs, then a row of prophets, and finally a row of patriarchs of the Old Testament. Above the middle door there is usually the deesis, a representation of Christ on his throne as ruler of the universe, with Mary and John standing to his right and left, in poses indicating that they are interceding for men. Thus the succession of images presents to the congregation the whole of the celestial Church. The pictorial content of the iconostasis corresponds precisely to the theological content of the Eucharistic liturgy. The icons carry out a liturgical function in still another manner. Each day, and especially each feast day, has its special icon. Thus, for Christmas the icon of the Nativity is brought out. These icons present believers with a picture of the sacred event which corresponds exactly with the established prayers and liturgical texts. For example, the Christmas liturgy — a body of venerable chants and prayers dating from the fourth to the ninth centuries-presents the traditional conception of the birth of Christ as taking place in a cave. The Christmas icons also set the scene of the Nativity in a cave. If the artist were allowed any latitude on this question and laid the scene — as Western painters do — in a stable, the mystical interpretations of the Nativity in the cave — interpretations in which the liturgy abounds — would suddenly lose validity. In this case as in so many others, the whole liturgical order of the Church depends upon the faithful reproduction of time-honored archetypes.

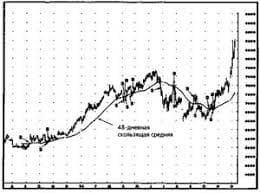

Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|