|

|

Liturgy and the Consecration of Icons.F urther evidence of the nature of the icon emerges from the procedure by which the priest dedicates a newly painted icon for service in a church. This act of consecration is absolutely essential, for it is the Church's confirmation of the identity between the painted picture and the celestial archetype. The liturgy used in present-day consecrations shows distinct traces of the conflicts that raged throughout the Church during the iconoclastic controversies of the eighth and ninth centuries. In those days the foes of icons appealed above all to the second of the Ten Commandments: “You shall not make yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything” (Exodus 20:4). They insisted that the Orthodox Church's veneration of images was a flouting of God's explicit prohibition of images. Such veneration, they held, was at the expense of the reverence due to God alone. The prayers and hymns used in the consecration of icons allude to both these arguments. The initial prayer stresses that in prohibiting images God was referring only to the making of idols: “By Thy Commandment Thou hast forbidden the making of images and likenesses which are repugnant to Thee, the true God, that they may not be worshiped and served as if they were the Lord.” After this statement the prayer points out all the more emphatically that God himself commanded “setting up of images which do not glorify the name of strange, false and nonexistent gods, but glorify Thy all-holy and sublime Name, the Name of the only true God.” Among such images the prayer mentions the Ark of the Covenant adorned with two golden cherubim and the cherubim of gold-covered cypress wood which God ordered to be installed upon Solomon's temple. Thus, after outlawing the idolatrous worship of false images, God began to depict the secrets of his kingdom in images. But God then performed the supreme act of self portraiture — the liturgical prayer continues — by becoming flesh, by the incarnation in his Son, who is the “image of the invisible God” (Col. 1:15) and who “reflects the glory of God.” God himself, “shaper of the whole of visible and invisible creation,” shaped an image of himself in Jesus Christ, his perfect icon. Thus God himself was the first icon maker, making a visible reproduction of himself in Christ. There now follows the most striking turn of phrase, and one that is most startling to western Europeans: the liturgy asserts that we have an image of Christ himself (who is the image of the Father), an image “not made by hands” which exactly reproduces the features of the God-man. The liturgy is referring to the miraculous image mentioned above which Christ sent to King Abgar of Edessa and also to the tradition of the cloth with which Christ dried his face on the way to Golgotha and which miraculously retained the imprint of his features. Christ himself, then, made the first Christ icon and thus legitimized both icon painting and the veneration of icons. This argument disposes of the iconoclasts' first objection. Their second objection, that veneration of the holy images robs God of the honor due to him alone, is confuted by a second argument drawn from Neoplatonic speculation on the problem of images. “We do not deify the icons, but know that the homage paid to the image rises to the archetype.” It is not the image which is the object or the recipient of veneration, but the archetype which “manifests itself” in it. In intercessory prayers, too, there is the parenthetic reminder that the images must not mislead anyone into withholding from God the veneration that is due to him alone as the archetype of all holiness.

Principal Types of Icons and their Place in Dogma.

Christ Icons. A particular type of image, which came more and more into use during the fourth and fifth centuries in representations of the holy sudarium [handkerchief used in Roman times for wiping away sweat] led to the dogmatic fixation of the Christ icon. The model was found in an apocryphal document of the early Church, the so-called Epistle of Lentulus. Lentulus is mentioned in ancient historical records as having been consul during the twelfth year of the reign of Tiberius. In the epistle Lentulus is identified as a Roman official, Pontius Pilate's superior, who happens to be in Palestine at the time of Jesus' appearance there, and who makes an official report to the emperor. The official report also included a warrant for the arrest of Jesus which ran as follows: “At this time there appeared and is still living a man — if indeed he may be called a man at all — of great powers named the Christ, who is called Jesus. The people term him the prophet of truth; his disciples call him Son of God, who wakens the dead and heals the sick — a man of erect stature, of medium height, fifteen and a half fists high, of temperate and estimable appearance, with a manner inspiring of respect, nut-brown hair which is smooth to the ears and from the ears downward shaped in gentle locks and flowing down over the shoulders in ample curls, parted in the middle after the manner of the Nazarenes, with an even and clear brow, a face without spots or wrinkles, and of healthy color. Nose and mouth are flawless; he wears a luxuriant beard of the color of his hair. He has a simple and mature gaze, large, blue-gray eyes that are uncommonly varied in expressiveness, fearsome when he scolds and gentle and affectionate when he admonishes. He is gravely cheerful, weeps often, but has never been seen to laugh. In figure he is upright and straight; his hands and arms are well shaped. In conversation he is grave, mild and modest, so that the word of the prophet concerning the 'fairest of the sons of men' (Ps. 45:2) can be applied to him.” The Byzantine Christ type is modeled after this description. He appears, however, in a number of different guises, depending on the aspect of Christ's nature which is being stressed: Christ as Lord of the universe (Pantokrator); Christ as Teacher and Preacher of the gospel; Christ as the Judge of the world, with stern countenance and “terrible eye.”

Icons of the Holy Trinity. Unlike the Christ images, the picture of the Holy Trinity cannot be traced back to a miraculous self-portrait. Nevertheless, it too must follow a strict canon. The theologians of the early Church searched the Old Testament for references to the Trinity. They settled on a passage that, but for their exegeses, would scarcely seem to have this hidden meaning, at least to the modern mind. The passage deals with the visit of the three angels to Abraham in the grove of Mamre (Gen. 18:9 ff.). The theologians of the early Church took this visit to signify a manifestation of the Trinity. Thus the first type of Trinity icon in the Eastern Church depicts the three angels appearing to Abraham in the grove of Mamre. A second type of Trinity icon depicts the Trinity as it is present at the baptism of Jesus. The Son stands in the waters of the Jordan; the Father is represented as a hand reaching down from heaven; and the Holy Spirit hovers above the Son in the form of a dove (Matt. 3:16-17). The New Testament yields two other pictures of the Trinity: the Pentecost scene, in which the Savior risen to heaven sits by the right hand of God, while the Holy Spirit, the “Comforter,” is sent down to the apostles in the form of tongues of fire; and finally the vision on Mount Tabor, in which the Father reveals himself as a voice from heaven — once again represented by the outstretched hand — the Holy Spirit appears in the cloud, and the Son is shown transfigured by light, as he appeared to the three disciples. There is a special formula with which these icons are consecrated. Both the Old Testament and the New Testament archetypes are invoked: “And as the Old Testament tells us of Thine appearance in the form of the three angels to the glorious patriarch Abraham, so in the New Testament the Father revealed himself in the voice, the Son in the flesh in the Jordan, but the Holy Spirit in the form of the dove. And the Son again, who rose to heaven in the flesh and sits by the right hand of God, sent the Comforter, the Holy Spirit, to the apostles in the form of tongues of fire. And upon Tabor the Father revealed himself in the voice; the Holy Spirit in the cloud; and the Son, in the brightest of all light, to the three disciples. So, for lasting remembrance, we profess Thee, sole God of our praise, we profess Thee not with our lips alone, but also paint Thy form, not to deify it, but so that seeing it with the eyes of the body we may look with the eyes of the spirit upon Thee, our God, and by venerating it we may praise and lift up Thee, our Creator, Redeemer and Uniter.”

Icons of the Mother of God. The New Testament lacks any such direct dogmatic basis for the icons of Mary. The Mariology of the fourth century had to create such a basis. To supply the want, there arose numerous legends revolving about the miraculous appearances of miracle-working images of the Blessed Virgin. In many cases the Mother of God herself was supposed to have appeared on earth. As a sign of her visit she would leave behind an icon whose supernatural light would attract the attention of chance passersby. Or else some believer would have a vision in which the hiding place of a miraculous icon would be revealed. A large number of Orthodox monasteries and churches not only in Russia but in other Orthodox countries were founded on the spot hallowed by the discovery of some such icon “not made by hands.” All consecrations of icons end with a prayer addressed directly to the person represented in the icon. Thus at the end of the consecration of the Christ icon the priest prays: “He who once deigned to imprint upon the sweat-cloth the outline, not made by hands, of his perfectly pure and divine-human countenance, Christ our true God, mild lover of men, have mercy upon us and save us.” Similarly at the close of the consecration of a Mary icon, these words are spoken: “We flee to Thy mercy, God-bearer; disdain not our cries of woe.”

Icons of Saints. The liturgy of consecration for the icons of saints makes it plain that the saints themselves, in their turn, are regarded as images of Christ. The Orthodox Church venerates the saints as “the hands of God,” by which he accomplishes his works in the Church; even after their deaths these saints perform works of love as intercessors and helpers and smooth their fellowmen's path to salvation. They are the earthly proof of the invisible celestial Church, whose purposes they implement. The Orthodox Church states explicitly that the saints do not obscure the greatness of Christ's person and works, but rather that all veneration offered to the saints returns to their archetype, Christ. The images of the saints are therefore reflections of the Christ image, which in turn is the renewal and perfection of the image of God implanted in the first man. Therefore the icons of saints are consecrated with the following formula: “Lord, our God, Thou who created man after Thine image and Thy likeness and, after this image was destroyed by the disobedience of the first created man, hast renewed it by the incarnation of Thy Christ, who assumed the form of a servant and became in appearance like unto a man, and whom Thou hast restored to the first dignity among Thy saints; in solemnly revering Thy icons, we revere the saints themselves, who are Thine image and Thy likeness. In venerating them we venerate and glorify Thee as their archetype.”

Icons of Angels. Along with the figures of the Evangelists and saints, the images of angels have a prominent place in Orthodox iconography. This is in keeping with the position of angels in the doctrines of the Eastern Church. God or Christ never appears alone; the divine Persons are always surrounded by a crowd of the heavenly host divided into various choirs. Chief in the hierarchy of the celestial Church is the Archangel Michael, the prince of angels, who leads the heavenly hosts in the struggle against Satan and his followers, and drives them out of heaven. But the lesser angels are also favorite subjects of Orthodox iconography. At one point in the liturgy of the Eucharist, angels are supposed to enter the church and join the priests, the deacons and the congregation in singing the cherubim's hymn of praise, “Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God of hosts” (Isaiah 6:3). Icons of angels as participants in the singing have their fixed liturgical place in the sanctuary as well as on the iconostasis.

Scenic Icons. Frequent subjects for icons are scenes and characters of the Old and New Testaments, which are the source of the principal Christian feasts, or important institutions of the Church. There are a whole series of icons relating to the monastic tradition. Scenes from the Old Testament are paired with scenes from the New Testament according to a fixed pattern of promise and fulfillment (see p. 30). Thus, for example, a favorite subject for icons is the prophet Elijah, who is considered the Old Testament prototype of Christian monasticism, forefather of those wise ascetics who fought demons in the desert and performed miracle upon miracle. Another favorite is John the Baptist, who is shown dressed in his hair shirt and living in the desert. These icons too conform strictly to liturgy. There is, for example, the so-called “Resurrection icon,” which, however, does not illustrate the Resurrection of Christ as we understand it and as it has been painted by Dьrer or Grьnewald — Christ breaking open the tomb and emerging from it. Instead these icons depict Christ's descent into Hades; he is shown storming the innermost fortress of Satan, or breaking the bars of the gate to the underworld, or lifting the gates of Hades from their hinges. On one such “Resurrection icon” Christ is shown standing upon the gates of hell which he has lifted from their hinges and arranged in the form of a cross; from the interior emerge the souls of the devout of ancient times, led by Adam and Eve who having been first to fall are the first to be liberated from Hades. Behind the first parents come the just patriarchs, kings and pious fathers of the Old Testament, who have been waiting all this time for their redemption. These icons are the counterparts of the Easter hymns of the Eastern Church, which take Christ's journey to Hades as their subject.

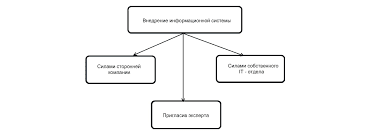

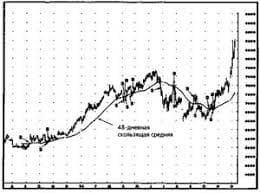

ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|