|

|

The Doctrine of the Trinity.The believers of the primitive Church had experienced the overwhelming reality of God in a threefold form. First, in the form of the Creator and Preserver of the universe, the Founder of the moral law, the Lord and Judge of nations and persons, the Lord of history, this was God as they knew him from the Old Testament. Second, they encountered God in the form of Jesus Christ, in the Son of God who had become Son of Man, in the incarnate Logos in whom they felt “the whole fullness of the presence of Deity.” Third, they encountered God in the wonderful plenitude of the works of the Holy Spirit, whom they saw operative in their midst in the various gifts of prophecy, annunciation, power over demons, healing, dominion over the elements and the raising of the dead. The liturgical worship of God in the form of Father, Son and Holy Spirit sprang from this direct religious experience and became established long before theological reflection had formulated the dogma. Examples of Trinitarian liturgical phrases can already be found in the New Testament. Nevertheless, theological clarification was absolutely essential, for the Jewish religion was based on uncompromising stress upon the oneness of God. How could the oneness of God, that cornerstone of both the Jewish and the Christian Scriptures, be reconciled with the fact that believers of Christian communities experienced God in this threefold aspect? This question appealed to the speculative bent of the Greek mind. In the course of the first few centuries of the Christian Church numerous solutions to the problem were proposed — so numerous that they comprise a branch of their own in the history of dogma. We cannot here trace all the steps of the discussion on the Trinity. In spite of all attempts at solution, the difficulty remained: in each particular case, members of the Christian community experienced the threefold God in one of his individual forms, in one of the personal manifestations of Deity. The believers felt that they had met separately the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit; they had distinct conceptions of the special qualities of each. The three manifestations had been concretely experienced, could be experienced by others, and therefore could not be wiped out by theological theorizing. And yet... was not God One? The Orthodox Church as an institution did not attempt a rational solution of this problem. The dogma of the Church merely tried to fit the mystery of the divine Being within a certain conceptual framework. It was concerned only with fixing two points: the oneness of the nature of God and the individuality and particularity each Hypostasis. Greek philosophy, with its metaphysics of substance and its doctrine of hypostasis, afforded a means for defining these difficult points. The paradoxical combination of unity and trinity was summed up in the formula: “Three hypostases in one Being.” The concept of hypostasy was later clarified by person — a word borrowed over from the language of Roman law because it seemed a better term for describing the particularity and individuality of the Hypostasies in God — Father, Son and the Holy Spirit. The various theological proposals for the solution of the problem of the Trinity constitute one of the most magnificent intellectual feats in the history of thought. But it must not be forgotten that these efforts to interpret the divine mystery were not the work of philosophers, who operate primarily in the realm of logical processes. Rather, the figures involved were charismatic personalities, men endowed with the gifts of the Spirit. Their theological endeavors were closely connected with liturgy, meditation and contemplation. Many of them were practicing ascetics, and they expressed their insights as much in hymns as in theological treatises. Ultimately all such speculation terminated in worshipful praise of the mystery of the Holy Trinity. The first Trinity canon of Metrophanes runs:

Engendered from Thee, O Father, there radiated divinely without efflux, as Light forth from the Light, the immutable Son; out of Thee also proceeds the Spirit, the divine Light. Believing, we adore the One Deity's three-personal glory; Him we praise.... Since Thou art source and root, as Father Thou art as it were the primal ground of the Deity of like nature in the Son and Thy Holy Spirit. Pour out to my heart Thy triple-sunned light and illuminate it by participation in the light that makes it like unto Divinity. The Holy Threeness and undivided Nature, undividedly divided into three persons and remaining undivided in the essence of Deity, let us, the earthborn, venerate Thee in fear and praise Thee as creator and Lord, Thou God of surpassing goodness....

As interpretations of the mystery of the Trinity grew, a striking difference sprang up in the course of time between the Orthodox and the Roman Catholic dogma. The point at issue was the question of the relationship of the Holy Spirit to the two other Persons within the divine Trinity. Biblical testimony offered only a single reference to the eternal procession of the Spirit from the Father. In that one reference the Spirit is distinctly differentiated from the temporal “sending” (John 14:26; 15:26) of the Spirit promised by Jesus during his mission upon earth. In the Eastern Church, the Father is regarded as the sole source and the sole First Cause both of the Son, who is begotten by the Father from eternity, and the Holy Spirit, who from eternity proceeds out of the Father. By contrast, in the West the Spirit is held to proceed from the Father and the Son. This doctrine has become established and has been interpolated into the Nicene Creed, which in its original form was accepted by both the Eastern and the Western churches. The original version taught only the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father. In the ninth century, however, Charlemagne effected this revision of the doctrine despite the initial resistance of the Pope; by insertion of the word filioque (and the Son) the Latin version of the Creed thenceforth spoke of the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son. This tampering with the wording of Christendom's central Creed, which had its fixed place in the Eucharistic liturgy, and hence was familiar to every believer, seemed to the Greeks an assault upon the innermost substance of the religion itself. For the Creed was one of the most venerable formulas of the Church and had appeared inviolable in all its terms. In later polemics the theologians of the Eastern Church always pointed to this revision of the Creed as the most significant sign of the Roman Catholic Church's deviation from the Orthodox faith. Orthodox theologians, in fact, have attempted to explain the subsequent evolution — which they consider a degeneration — of both the Roman Catholic West and its dialectical opposition, the Protestant Reformation, as resulting from this wrongheaded interpretation of the dogma of the Trinity. They have gone so far as to dub the whole of western European culture a “culture of the filioque,” that is, a culture stemming from this Western betrayal of the original verities of the religion.

The Christology. The dogmas concerning Jesus Christ also derive from spontaneous religious experiences of the primitive Church. The believers of the early Church had acknowledged Jesus as the incarnate and resurrected Son of God. They regarded the testimony of the disciples, who had witnessed the epiphanies, as proof that he was indeed the exalted Lord who sits at the right hand of the Father and would return in glory to bring about the fulfillment of his kingdom. The Christological formulas of the Eastern Church do not try to provide a rationalistic explanation of the phenomenon of Christ. They aim to bring out at least the three aspects of the mystery of divine Sonship which the Church regarded as essential. First, the fact that Jesus Christ, Son of God, is God in full measure, that in him “the whole plenitude of Deity is present.” Second, that he is man in full measure. Third, that these two “natures” do not exist unconnected side by side, but that they are joined within Christ in a personal unity. Thus the concept of the sameness of substance — homoousia — of the divine Logos with God the Father made explicit the truth of the full divinity of Jesus Christ. The mystery of the person of Jesus Christ could then be summed up in the formula: two natures in one person. Once again the concept of person developed by the Roman law became useful for conveying the concept of the fully divine and fully human nature within a single entity. What we have said concerning the development of Trinitarian doctrine also applies to the elaboration of the Christology: it was not the product of abstract logical operations but sprang from the liturgical and charismatic realm of prayer, meditation and asceticism. The dogma of Christ is not intended to be abstract theory; it is forever being re-expressed in the many hymns of the Eastern Church. The Easter liturgy puts it: “The King of Heaven appeared on earth out of sympathy for man and associated with men. For he took his flesh from a pure virgin and, assuming it, came out from her. One is the Son, twofold in substance but not as a person. Therefore, proclaiming him perfect God and perfect man in truth, we confess him Christ, our God.”

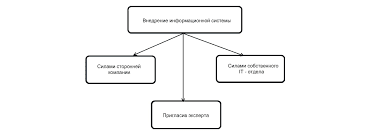

ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|