|

|

The Old “Schismatic” Churches.T he splintering-off of the old so-called “schismatic” churches was brought about by both political and dogmatic causes. In considering this matter we must again remember the multiplicity of forms in the early Church. Uniformity could be achieved only by enthroning one of the existing types as orthodox and branding the others as heretical. Constantine the Great had transformed the Christian Church, hitherto the Roman Empire's most dangerous foe, into an agency for restoring the unity of the Empire, for he rightly recognized that any such unity had to be founded on a spiritual and religious basis. Thus the unity of the Church became a political factor of the first importance. Unity of the Church had to be imposed for the sake of unity of the Empire, and Constantine and his successors bent every effort to enforce it. In the ensuing struggle all the rival factions strove above all to gain the emperor's ear. The victorious party could have opponents declared heretics and condemned as enemies of the state. From that time forth, the unity of the Imperial Church coincided with the limits of the Empire's power; in East and West unity ended and multiplicity began where the political arm of Byzantium was no longer strong enough. The special course taken by the Church of Rome, whose bishops sought to enforce their claims to primacy with the aid of the young barbarian kingdoms of the North, was possible only because Rome lay outside the sphere of Byzantium's political power. The fact that ecclesiastical factions that quarreled with an edict of the Imperial Church were declared heretical, and their members persecuted as enemies of the state, led to an inextricable mingling of ecclesiastical and political elements. We shall mention only two of the numerous consequences: Either the leaders of the minorities emigrated into enemy states bordering on the Byzantine Empire and established centers from which they combated the Byzantine Imperial Church and its theology, the while subverting local churches that were outside the direct control of the Empire; or despite the pronouncement against them, the leaders of such dissident groups stood their ground and collected so strong and loyal a body of followers that the authorities of the Empire were not able to impose their will upon them. Such groups had a better chance of withstanding pressure if they were established in border areas threatened by external enemies.

The Nestorian Church. The Nestorians were an example of the first type of dissidence. When the Imperial Church decided officially against the Christology of Patriarch Nestorius of Constantinople, his followers emigrated to eastern Syria and Persia. They impressed their theological views upon the Persian Church. The ideological breach was followed by organizational separation; the Persian Church broke with the patriarchate of Antioch. Persia, the archenemy of Byzantium, adapted an ecclesiastical structure antagonistic to the Church of the Byzantine Empire. Missions sent out from Edessa in eastern Syria, and later from Persia, operated throughout India and central Asia, China, Mongolia and southern Siberia (see p. 126 ff.).

The Monophysite Churches. The Monophysite churches are an example of the second type of resistance. Not only theological factors but national and racial ones played their part in the genesis of these churches. Monophysite doctrine emphasized the divine nature of Jesus Christ almost to the point of excluding his human nature. Adherents of this view had won the majority at the “Robber Council” of Ephesus in the year 449 and had succeeded in foisting their interpretation upon the theology of the whole Imperial Church. But only two years later the Council of Chalcedon condemned their doctrine as heretical. The two theological parties were so evenly divided in numbers and strength that the doctrine of Chalcedon could not win out either. The condemnation of the Monophysites led to a split, the Armenian, Coptic (Egyptian), Ethiopian, and the larger part of the Syrian and the Mesopotamian churches adhering to Monophysitism. Doctrine alone was not the sole divisive factor, for all these churches had already developed an independent church life in their own languages. The influence of “non-theological” factors in turning the Egyptian Church to Monophysitism are particularly patent. The Monophysite doctrine was the logical outgrowth of views on the nature of Christ which had been advocated by some theologians of Alexandria. When the Council of Chalcedon condemned the doctrine of one nature in Jesus Christ, Egyptian nationalistic feelings were hurt. Significantly enough the native Copts rather than the Egyptian Hellenes were most strongly wedded to traditional Monophysite ideas. Factional feeling was intensified by the strains between the Copts and the Greeks, who were the economic and intellectual leaders of Egypt. A further element was the traditional rivalry between Alexandria, with its ancient claims to ecclesiastical primacy, and Constantinople — the Alexandrians regarding the latter as a parvenu city in Church affairs. The enmity between the churches was deepened by Byzantium's belated efforts to install Orthodox patriarchs of Greek origin in place of the banished Monophysite bishops. The native Copts deeply resented this. The conflict ultimately benefited the Moslem Arabs, for a good many of the Monophysite Copts hailed them as liberators from the yoke of Byzantine Orthodoxy. Once entrenched in Egypt the Arabs oppressed the Copts and forced the religion of Islam upon them. Because it had ties with the Egyptian Church dating back to the early missions, the Ethiopian Church has remained Monophysite to the present day.

Centralism in the Orthodox Church. Throughout the history of the Orthodox Church, the tendency of the linguistic and national branches to split off into autocephalous national churches was a source of constant instability. These churches were always straining against the unifying aims of the Byzantine Church. Until the Turks captured Constantinople in 1453, the Byzantine Church was forever struggling to prevent the formation of new, independent national churches and maintain jurisdiction over the outlying territories. Where this proved impossible, Constantinople made an effort at least to keep the strategic ecclesiastical positions in the hands of Byzantine Greeks. In many Slavic churches, for example, stubborn battles developed between the Greek and the native clergy for possession of the most important episcopal seats and other influential church posts. The linguistic contention between Slavic and Greek liturgy in the Serbian, Bulgarian and Romanian churches was never wholly settled. In the Oriental provinces of the Church also, the rivalry between the Byzantine-minded Greeks and the native ecclesiastics produced constant tensions and at times open conflicts.

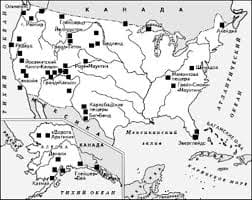

Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|