|

|

Coordination of the Liturgy in the Byzantine Imperial Church.The older liturgies that have come down to us — above all, the Didache, the “Clementine” liturgy, the Syrian liturgy, the St. James' liturgy of the Church of Jerusalem, the Nestorian and Persian liturgies, the Egyptian liturgy that goes by the name of St. Mark's, the Euchologion of Serapion, the liturgy preserved in the Egyptian Church which probably goes back to Hippolytus — all these convey an impressive picture of variety. The coordination of liturgy took place only in conjunction with the extension and nationalization of the Byzantine Church. Finally, from the sixth century on, two standard types of liturgy were established under canon law. The first was the so-called liturgy of St. John Chrysostom; it is patterned closely after the liturgy traditionally employed in the city of Constantinople. Bearing the name of one of the most famous Ecumenical Patriarchs, this liturgy spread from Hagia Sophia throughout the whole of the Byzantine Church, just as in the Carolingian Empire the liturgy employed in the Roman Mass was established as the standard. This meant the extinction of the numerous other liturgies that had been in use within the far-flung sphere of the Byzantine Church, just as the Carolingian reform spelled the doom of the older Gallican, Mozarabic and Celtic liturgies, which, incidentally, bore a close resemblance to Eastern liturgy. Alongside the Chrysostom liturgy, St. Basil's liturgy also survived, thanks to the enormous prestige and power of monasticism in the Orthodox Church. St. Basil's liturgy — which probably was created by that famous Church Father — was originally the liturgy of the Cappadocian monasteries. It could scarcely be banished from the Byzantine monasteries, but it is celebrated only ten times a year. In addition to these two liturgies there is a third called the “Liturgy of the Presanctified Elements.” It is ascribed to Pope Gregory the Great. This liturgy is unique in that the consecration of the Eucharistic elements is absent from it; communion does indeed take place, after the verbal part of the service is spoken, but the necessary Eucharistic elements have been consecrated on the preceding Sunday. This liturgy is celebrated mornings on the weekdays of Lent and from Monday to Wednesday of Easter week. This hoard of richly varied liturgies testifies to the existence of an enormous creative freedom during the early centuries of the Christian era. This freedom must have been accompanied by a religious йlan, a capacity for liturgical improvisation, such as no longer exists and such as we find difficult even to imagine. This does not mean that the liturgy was the product of arbitrary individual decisions. Rather, it drew upon already existing liturgies from various sources, combining and modifying these into new forms that expressed the charismatic impulses of the Church.

Variety within the Liturgy. The proclaiming of a specific, official standard for the entire Orthodox Church did not mean a “freezing” of the liturgy. The impulse toward variations in the divine services could find expression in the most multifarious ways. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, as in the Roman Mass and the Roman Breviary, a distinction is made between “fixed” and “alternating” parts. While the fixed parts of the order of divine worship are unalterable and form the basic structure of any given service, the individual character of the service or the particular Church feast can be given its due in the movable parts. These parts consist of readings from the Old and New Testaments which are relevant to the special nature of the given feast and of prayers and hymns. They constitute one of the spiritual treasures of the Eastern Orthodox Church; for the Church is rich in the possession of hymns by her greatest holy men and inspired saints. These are incorporated into the very liturgy of the Church and thus are kept alive by the body of believers. All aspects of the liturgy show this fundamental variety.

The Liturgical Gestures. The Orthodox Church can draw upon a great wealth of liturgical gestures. In most Protestant churches it is customary for worshipers to sit on chairs or benches while sending their prayers up to God. This practice is unknown in the Orthodox Church and would be incomprehensible to the Orthodox believer. For he takes part in services standing and prays standing, with his arms at his sides, except when he crosses himself at the beginning and end of the prayer. The commandment to stand is explicitly stated in the liturgy: Before the reading of the Gospel the priest, standing at the royal gate of the sanctuary, cries out, “Wisdom! Let us stand erect!” [Clasping hands in prayer is unknown to the Orthodox Church. This gesture derives from an ancient Germanic tradition; it symbolizes the prisoning of the sword hand by the left hand — in other words, making oneself defenseless and delivering up oneself to the protection of God. The Roman Catholic gesture of palms pressed together, fingertips pointing upward, symbolizes the flame; it too is unknown in the Orthodox Church.] However, the gamut of gestures in use in the Eastern Church is great: crossing; bowing with arms dangling; kneeling; touching the floor with the hand; prostration on the floor, arms outstretched, forehead pressed against the floor. As a penitential gesture there is the crossing of arms and pounding on the chest. The liturgists pray standing, sometimes with arms outstretched in the form of a cross, sometimes crossed over the chest. Even the gesture of prayer used in antiquity — both arms held up, palms turned upward — is employed for certain passages of the liturgy, for example, for the eulogy of the cherubim and for invoking the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Eucharistic elements. In addition there are many other gestures of worship and adoration: kissing the holy icons, kissing the altar, the Gospels, the crucifix with which the priest dispenses the concluding blessing, kissing the hem of the priest's robe.

The Liturgical Vestments. Great variety is also exhibited in the liturgical vestments, whose embellishment has become a highly developed branch of sacred art. These robes have a symbolic significance which is set forth in the preface to the Eucharistic liturgy, the proskomide. Before beginning the service of the Eucharist, priests and deacons don the holy vestments in the sanctuary behind the iconostasis. As they do so they speak certain prayers that proclaim the spiritual meaning of their act. Donning the ecclesiastical robes is a symbol for donning a new spiritual nature, the assumption of a celestial body. In putting on these spiritual garments the celebrant is the representative of paradisial man as he will achieve restitution and perfection in the kingdom of God. As he dons the long, smooth undergarment, the sticharion, which corresponds approximately to the Roman alb, the priest pronounces the following prayer: “My soul rejoices in the Lord; He has dressed me in the garment of salvation and put upon me the vestment of joy. Like a bridegroom He has placed the miter upon me, and like a bride He has surrounded me with adornment.” The note of nuptial rejoicing is sounded even in these preparations for the Eucharist: in changing his dress and putting on his new nature, the priest becomes bridegroom and bride. The next article of dress, the epitrachelion, corresponds to the Roman stole. It is worn by the Orthodox priest around his neck, and the dangling ends are sewed together over his chest. It signifies the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. In putting on this garment the priest says: “Praise be to God who has poured out His grace upon His priests like precious ointment upon the head; it flows down upon the beard, yea, upon the beard of Aaron; it flows down upon the hem of his garment.” In donning the girdle the priest prays to God: “He who has girded me with strength and made my way irreproachable.” Similarly, in putting on the epimanikia — cuffs reaching from wrist to elbow, somewhat resembling the Roman maniple — the priest says as he places it on his right arm: “Thy right arm was glorified in strength, O Lord; Thy right arm, O Lord, shattered the enemy”; and for his left arm: “Thy hands have created me and formed me; teach me, that I may know Thy commandments.” The donning of the phelonion [chasuble], which like the Lord's tunic is seamless (John 19:23) and whose color conforms to the calendar feast to be celebrated, is compared with the “clothing of the priests in righteousness” (Ps. 132:9).

Liturgical Symbolism: “Promise” and “Fulfillment.” It is not easy for the non-Orthodox to understand the language of the Orthodox liturgy, for a special mode of thought underlies the texts and hymns — a way of thinking primarily in symbols and not in abstract concepts. This very fact gives a singular unity to liturgy, meditation and prayer. The majority of the images that serve as signs and symbols of particular spiritual processes are derived from the immeasurably rich pictorial world of the Old and New Testaments. They are, therefore, already sacral images. But these images are not beheld in terms of their literal, superficial pictorial values; they are linked to one another in a special “mystical” fashion. The basic underlying idea is that the Old and New Testaments stand in a mysterious relation of “promise” and “fulfillment” to one another. The Old Testament represents the era of the promise; in it the great mysteries of the New Testament — the era of fulfillment — are prefigured in prophetic signs and symbols. Thus the Old and New Testaments are interwoven in a pattern of redemptory correspondences. Early examples of this thinking in terms of correspondences can already be found in the arguments of the Apostle Paul — when, for example, he interprets the cloud in the desert as a foreshadowing of the mystery of baptism, or when he sees the rock that moved through the desert giving water to the people of Israel as the symbol of Christ (1 Cor. 10: 1 ff.). In the Alexandrian school of catechumens, this typological, anagogic interpretation of the Old and New Testaments was set up as a regular method of scholarship and theology. The mode of thinking operating in this linking of symbols springs directly from the kind of typological exegesis taught by Clement of Alexandria and Origen. A simple example will cast light on the nature of this figurative thinking. During the first week of Lent the prayers and hymns in the liturgy deal with the theme of fasting. Fasting itself is described in sheer imagery. The triodion of Theodore of Studion which belongs in the liturgy for Monday morning of the first week of Lent, goes as follows: “Now it is come, the true time of the struggles for victory has begun. Let us joyfully begin with fasting the racetrack of the fasts, carrying virtues as gifts before the Lord.” Here the thought is couched in terms of the images of racing and competition, favorite images of the Apostle Paul's. Monday of the first week of Lent is the beginning of the contest in which the Christian drives his chariot on to the racetrack of fasting in order to strive for the victory of holiness. Another device is the use of typological images. In another ode by Theodore of Studion we find: “Purified by fasting on Mount Horeb, Elijah saw God. We too wish to purify our hearts by fasting. Thus we shall see Christ.” Here the prophet Elijah is invoked, who, as the prototype of the ascetic of the desert, is the Old Testament sponsor of fasting. In another ode by the same hymnist, fasting is again traced to sacred prototypes: “By the measure of his forty day fast the Lord consecrated and hallowed the present days, O brethren. In these days, then, let us cry out eagerly: Christ praises and raises into the eons.” Here Christ himself, he who has fulfilled the redemption, appears as the archetype of fasting. His forty-day fast in the desert serves as an example for all his disciples; from it springs the whole principle of ecclesiastical fasting, which has been set up as a general Christian road to sanctity. This same type of figurative thinking underlies the liturgical texts of all the mysteries; in each case they are related to and justified by archetypes from the Old and New Testaments.

The Sacraments.

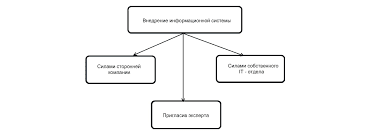

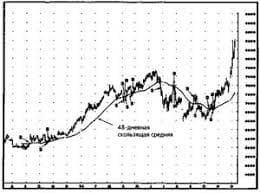

ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|