|

|

VII. Missionary Work and the Spread of the Orthodox Church.

Orthodox Missions. T he Eastern Church has often been charged with failure in its missionary work. Prejudiced observers have contended that it felt little impulse to convert the non-Christian peoples living in its midst or at its borders, that it was satisfied with preserving the status quo and preferred to keep its dogmas and liturgies to itself. A prejudiced opinion of this kind is largely due to ignorance, in western Europe, of the actual missionary work carried out by the Eastern Orthodox Church. It is also, perhaps, based upon the situation of the Orthodox remnants who found themselves engulfed by the triumphant sweep of Islam in the Near East and central Asia. It is true that the tiny colonies of Orthodoxy in Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, Egypt and Ethiopia, as well as the Orthodox Thomaeans in India, and the battered Nestorian Church in Persia, display little missionary activity today. During the first spread of Islam, during the time of the Mongol hordes in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and again since the establishment of Turkish rule, these churches were subject to such violent persecution that the once flourishing Christian communities were almost wiped out. The Mohammedan authorities have forbidden the survivors to undertake any missionary work among Muslims. Islamic law, moreover, provides the severest penalties for the conversion of Muslims to Christianity. The Indian Thomaean Christians have become, under the influence of Hindu ideas of caste, a closed caste and have thus forfeited all missionary aspirations. Centuries of political repression of the Orthodox and schismatic churches in the Near and Far East snuffed out whatever missionary zeal might have been felt by those beleaguered Christians. Even when times changed and repression was lifted, these churches were no longer capable of recovering their militancy. During the period of European colonial expansion Britain and France in particular wrote clauses concerning missions into their international treaties. Thus Roman Catholic and Protestant missions were able to begin their operations in the Near East under the most favorable terms. The contiguity of active Roman Catholic and Protestant missions in the Near East, alongside the old Christian churches whose character was stamped by centuries of passivity, greatly contributed to this notion that Orthodoxy is incapable of missionary work.

The Missionary Methods of the Byzantine Church. I t is, however, altogether wrong to conclude, from instances of this sort, that the Eastern Orthodox Church has completely lacked the missionary spirit from the beginning. In fact, Orthodoxy engaged in the most vigorous missionary work during the period of its own most vital growth. By the third and fourth centuries it had penetrated eastward as far as Persia and India, and from those countries, in its Nestorian variety, to China, central Asia and Mongolia. It was also expanding westward; the Germanic tribes migrating through western Europe were first Christianized by missionaries from Asia Minor and Byzantium. The Byzantine Church also sent its missionaries to the north, northeast and northwest; West, South and East Slavs were converted by them. Much of this missionary activity was subsequently forgotten by the West because Roman Catholics later replaced the Orthodox missionaries, especially in Moravia, and incorporated the Germanic and West Slavic tribes into the community of the Roman Catholic Church. In its time, however, the missionary work of the Orthodox Church was a tremendous achievement, and its aftereffects survived for centuries, though overlaid by later Roman Catholic work among the heathen. We shall deal with the missionary activity and spread of the Orthodox Church in some detail for the very reason that it has been so largely ignored by the West.

Mission and Nationality. I n its most flourishing period the Orthodox Church not only poured much of its spiritual dynamism into spreading the gospel among non-Christian peoples, but did so in consonance with a theological principle that distinctly furthered the success of this missionary work. The principle was: to preach to the various peoples in their own language, and to employ the ordinary tongue of the people in the liturgy for divine services. In the Syrian Church, Syrian; in the Armenian Church, Armenian; in the Coptic Church, Coptic; in the Georgian Church, Georgian; these were the languages of sermon, hymn and liturgy. Behind this practice lay a specific theological view of the vernacular. The primitive Church had consulted the Bible and drawn from it certain conclusions concerning man's linguistic evolution. Thus, the early theologians set up two parallel events: one was the story of the confusion of tongues at the Tower of Babel, and the other the story of the Pentecostal outpouring of the Spirit with its accompanying miracle of “speaking in tongues.” These were regarded as key points in the history of redemption. The confusion of tongues at Babel (Genesis 11) was seen as punishment for man's defiance of God. The many languages thus engendered destroyed the unity of true knowledge of God and promoted the spread of false religions, so that each people created its own gods. The “miracle of tongues,” on the other hand, was a token of God's mercy and his desire to redeem all nations. The Pentecostal miracle was considered to be the baptism of the vernacular tongues; henceforth the vernacular was exalted into an instrument for annunciation of the divine message of redemption throughout the world, among all peoples. These concepts are still impressed upon the Orthodox believer, for they are incorporated into the liturgy:

“With the tongues of foreign peoples hast Thou, Christ, renewed Thy disciples, that they might thereby be heralds of God, of the immortal Word that vouchsafes to our souls the great mercy.... Upon a time the tongues were confounded by reason of the Tower's blasphemy. But now tongues are filled with wisdom by reason of the glory of knowledge of God. Then God condemned the blasphemers by sin; now Christ has illuminated the fishermen by the Spirit. Then the garbling of language was imposed for punishment; now the harmony of languages is renewed for the salvation of our souls.... The power of the divine Spirit has solemnly united into one the divided voices of those who agreed ill in their thoughts, has joined them in concord by giving to the believers insight into knowledge of the Threeness in which we were confirmed.... When, descending, He confused the languages, the All-highest divided the peoples. When He sent out the tongues of fire, He called all to oneness. And in concord hymn we the Allholy Spirit.”

Since this was their belief, Orthodox missionaries of all countries and all epochs made a point of casting both gospel and liturgy into the vernacular of the peoples of their mission. Thus it was that the Orthodox missions in both West and East, in the Germanic, Slavic and Asiatic lands, had an enormously creative influence upon the development of the vulgar tongues. Many of the languages of Europe, the Near East, Siberia and central Asia were raised to the rank of literary languages by the work of the Orthodox missionaries in translating the Bible and liturgical writings. Nowadays few people realize the significance of such translations. Translating the Bible into a vernacular means enlisting that language for the work of building the kingdom of God. The language is used to build the spiritual edifice, and lines are laid down governing its further literary development. Such a translation brings about both the rebirth and baptism of a language. The translator of the Bible is confronted with the creative task of expressing, with the often inadequate means of a hitherto nonliterary vernacular, the immense body of spiritual and earthly, natural and social, sacred and profane ideas that are contained in the books of the Old and New Testaments. To perform such translation means, in fact, to conquer for the first time the intellectual and natural universe for the language in question, and therefore for the people who speak that language.

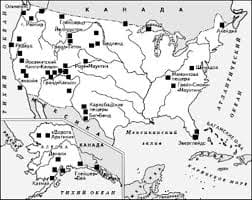

Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|