|

|

The Struggle between Cenobitic and Skete Monasticism.The emergence of two different types of monastic institution on Russian soil affected the whole history of Russia. As time went on and political conditions changed, these two types of monasticism, so different in their internal and external structures, were often pitted against each other. The antagonism grew particularly bitter during the fifteenth century. The two brands of monasticism differed in their attitude toward the state, and toward the question of monachal property. Skete monasticism, so christened from the Greek word for eremitism, was responsible for the great missionary work of the Russian monks in northern Russia and Siberia — work we shall later examine in some detail. The skete monks turned away from politics; they were preachers of love and gentleness. As such they naturally opposed the injustice of princes and of the ecclesiastical hierarchies as well. Above all they denounced the cruel methods that the ecclesiastical authorities were beginning to apply to heretics and schismatics. The other type of monasticism, which continued the tradition of founders' monasteries, ranged itself on the side of the secular princes. Strictest discipline prevailed in these monasteries. The monks sought to increase the wealth of their foundations in order to feed the poor and to help the population in times of famine. Such monastic social work was vitally important to the Grand Duchy of Moscow. Yosif of Volokalamsk (1439-1515), one of the outstanding disciples of the greatest Russian abbot, St. Sergei, set the style for the whole of the Moscow hierarchy and for monastic institutions throughout the duchy. His partiality for strict discipline also colored his political viewpoint. Yosif became the theological defender of tsarist autocracy and dedicated all his energies to strengthening Orthodox tsarism. He not only established the ideology of Russian ecclesiastical statism but also was responsible for Orthodoxy's unbending harshness toward heretics and schismatics. During the last years of the reign of Ivan III (14621505) he personally persuaded the grand duke to undertake harsh punitive measures against heretics. At the beginning of the sixteenth century the two monastic movements came to a direct clash. The Yosifites, as the advocates of an established church and tsarist autocracy were called, began to persecute the skete monks who lived in the lands beyond the Volga. At first the struggle revolved around the question of monastic property; after the 1550s it centered around the treatment of heretics. The monks beyond the Volga were consistently opposed to any use of force by the Church. They gave refuge to heretics persecuted by state and Church, and were therefore accused by the Yosifites of being themselves heretics. Finally their monasteries were dissolved and the monks themselves thrown into prison. The whole skete movement was annihilated. From that time on the triumphant Yosifites wielded the dominant influence in the Church of Muscovy. Their victory was inevitable for their aims accorded with the political aims of Moscow, whereas the skete monks had given government circles a wide berth. They would leave their hermitages to perform charitable services, but they never went to the palaces of the nobility or to Moscow itself. Like Gennady († 1565), the builder of the monasteries of Kostroma and Lyubimograd, they had loved to talk with peasants and stay in peasant huts where they could carry out their pastoral duties among the common people. The dissolution of skete monasticism was a severe blow to the religious life of Russia. The tension between a free, charismatic, missionary-minded monasticism on the one hand and an authoritarian, statist monasticism on the other had proved an enormous spur to religious life in the Duchy of Kiev and later in Muscovy. Now that tension was gone; the state-church party had won a total victory. Thereafter the libertarian ideas that had been the property of eremitism were never allowed to gain foothold in Russia. Thus the dissolution of skete monasticism was the prelude to the subsequent tragedy: that Russia was left totally at the mercy of an intellectually paralyzed statist ecclesiasticism. The state asserted its supremacy in a series of repressive acts. Peter the Great eliminated the patriarchate; Empress Anna Ivanovna cruelly persecuted the monks; the ukase of 1764 closed more than half of all the monasteries in Russia. During these dark times the forbidden original spiritual impulses of Russian Christianity forced their way to the surface only within staretsism (see p. 99).

Orthodox Monasticism Today.

Principal Types. Present-day Orthodox monasticism displays great uniformity of underlying ideas. True, every monastery has its own statutes, but their rules derive from the monastic rules of St. Basil, St. Sabas, St. Athanasius of Athos, and St. Theodore of Studion and are thus basically similar. The majority of present-day Orthodox monasteries are still of the old-type cenobitic pattern, in which all the monks lead their common life under the direction of a hegumen or abbot. Services, meals and work are shared. The monks sleep in common dormitories. The hegumen is elected by the monks and must be confirmed by the diocesan bishop or the patriarch. The monks of the cenoby are obliged to obey the hegumen unconditionally. Private property is forbidden. In some monasteries, however, complete sharing of a common life has been partly or wholly abandoned. As long ago as the reign of Justinian, some monks in cenobitic monasteries were allowed to live as anchorites in special rooms. The impulse toward a more individual form of sanctity led, toward the end of the fourteenth century, to the special “idiorrhythmic” type of monasticism. The purpose of this was to maintain the monachal framework and yet to permit the freedom and independence of the strictest type of sanctity, that of the anchorite. As it turned out, this variation in the pattern of cenobitic monasticism led to a loosening of the latter's austere discipline. The tie between idiorrhythmic monasticism and old anchoritism is obvious. The monks subscribing to this rule live in small colonies of sketes or huts, as did the early Christian monastic colonies. The custom is for groups of three monks — a “family” — to live together in a single hut. Devotions are performed in the chapels of the separate huts. The monks of different sketes meet in the village church of the monastic settlement only on Sundays and holidays. Alongside this practice, the pure type of anchoritism has survived to this day. The eremite lives in a hut near the monastery that supplies him with his food, or in a hermitage in some inaccessible place in the wilderness, or on a rocky cliff. There are still such eremites today on Athos, especially in the cliffs of the eastern peak of Mount Athos. The terrain here is so precipitous that the anchorites' huts often can be reached only by rope ladders.

Asceticism. A great many specifically Oriental characteristics of asceticism, reminiscent of Hindu or Buddhist ascetic practices, have lingered on in Orthodox monasticism. The stylite saints of Syrian monasticism, for example, can be traced to such non-Christian traditions. The anchorite established himself upon the capital of a solitary pillar, usually the remnant of some ancient temple, and remained there in a state of “eternal prayer.” The fact that he never ceased meditating was expressed in his physical posture also. The ascetic assumed an attitude of prayer and remained so still that ultimately — at least according to the legends — several Syrian saints had birds nesting upon their heads or upon their outstretched hands. In Russia other saints won fame for extreme physical penances: fasts of up to forty days, prostrations repeated thousands of times — the penitent throwing himself down with arms outstretched and beating his forehead against the ground — attaching massive iron chains to themselves or wearing heavy metal crosses studded with sharp points against their bare skins, under their habits. Such instruments of castigation are still to be seen in the museums of Orthodox monasteries. A certain relaxation of the austerity of cenobitic monasticism was introduced in the eighth century, with the distinction between the “micromorphic” and “macromorphic” monks. “Micromorphism” was introduced as a form of postulancy. By the vow of “macromorphism” the monk takes upon himself the full austerity of monastic life. A lesser degree of sanctity is required of the micromorphs. Acceptance into the rank of macromorph is marked by a special liturgical act, in which the stricter vows are pronounced. As a rule this is done only after the monk has undergone monastic life for many years in the rank of micromorph.

Attitude toward Learning. Orthodox monasteries have never become centers of learning in the same sense as the Roman Catholic monastic orders. This is due to the fact, already noted, that the Eastern monks dedicated themselves entirely to liturgy, preyer and contemplation. Their fundamental attitude of withdrawal from “the world” led to their turning their backs on all forms of secular knowledge. Secular learning was regarded as an inducement to vanity and pride; for the holy man, it was better to steep oneself in the “folly” of the gospel. Whereas Western monasticism, especially the more recent orders, has contributed greatly to many fields of scholarly endeavor and monasteries today have become centers of historical research, the only branch of knowledge that has developed in the Orthodox monasteries has been the study of spiritual life and liturgics. The spirit of scholarship has more and more faded since the apogee of Byzantium. There have been some exceptions, to be sure: personalities like Maxim Grek (†1556), a celebrated Greek theologian and monk of Athos who was sent as a delegate to the court of the Russian tsar and was then kept in Moscow against his will. But his efforts to lend new impetus to theological studies had only limited success. On the whole the Orthodox monasteries have remained places for liturgical and meditative devotions. When at the beginning of the nineteenth century the Greek theologian Eugenios Bulgaris (1716-1806) attempted to found a theological academy on Athos, he met with furious resistance from the monks. The ruins of the great academy building remain there to this day, a monument to a lost cause, for the monks set it on fire.

Russian Staretsism. B ut if Orthodox monasticism contributed little to the advancement of knowledge, it played a great part in the spiritual education of the people in another sphere. This sphere was pastoral care, the “cure of souls.” Especially within Russia the example of the monks was a living force for piety. Orthodox Russian cenobitic monasteries permit monks of proven virtue to leave the community and live as anchorites in the vicinity of the monastery. The Russian name for such anchorites is staretsy, meaning those who build their cells in the woods. Throughout the centuries outstanding Russian staretsy have been the spiritual guides of princes and tsars, of philosophers and writers. They have also had a great effect upon the ordinary people of all classes.

Monasticism and Mysticism. T he monastic orders were the cradle of the most important spiritual force in Orthodoxy, contemplative life. Its fundament was asceticism. As we have seen, the primitive Church's ascetic traditions, woven of elements taken from the Gospels, have remained almost unaltered down to the present day. In the early days of the Church, however, asceticism was more strongly influenced by expectation of the impending end of the world and the dawn of the kingdom of heaven. Ascetics prepared for the coming of the kingdom by vanquishing what was worldly in themselves. The monk's task was to devote himself wholly to God in mystic contemplation and to withdraw as far as possible from all involvement in the things of the flesh and of this world. This total devotion to God was so radical and exclusive that ultimately it took precedence over one's obligations to one's fellowmen. The highest form of asceticism was supposed to be complete liberation from the “world” (sinful life), solitude in which the pious monk's entire moral and intellectual energies were directed toward God. The conditions of the monastery were intended to further the prayer and contemplation that were the monk's principal task. The monastic state, therefore, is still referred to as the state of “angelic life.” Similarly the habit worn by the monk is referred to as the angel's robe. The ascetic who frees himself from all temptations of this world feels that right here on earth he is concentrating his efforts upon the kingdom of heaven. His aim is to achieve union with the celestial world in this life. This union takes place by way of Christ, the divine Logos, who has descended to earth and opened the way for men to become divine themselves. However, the monk's spiritual experience, in which he participates in union with the transcendental world, is not restricted to the level of “Christ mysticism,” that is to say, becoming one with Christ. It rises to “God mysticism,” in which the monk, through experiencing union with Christ, the Image of the Father, achieves a vision of the divine Light Itself. The most sublime expression of this monastic contemplative life became the doctrine of hesychasm,[5] which was most assiduously developed on mount Athos in the fourteenth century. The peak mystical experience of the hesychastic monks is vision of the divine Light which comes as the reward of methodically practiced contemplation. This ascetic monastic mysticism was celebrated in the poems of the great Byzantine hymnists, above all those of Simeon the New Theologian (c. 960-c. 1036). Such mystical hymnody has been kept alive in the Orthodox Church down to the present time by being incorporated into the liturgy and thus presented to churchgoers of every parish in daily or Sunday prayers and hymns. The principles of self-abnegation are spelled out in the liturgy of consecration of a monk. After the abbot has put numerous traditional questions to the novice, he addresses him with the following formula: “If you now wish to become a monk, purify yourself above all things of every taint of the flesh and the spirit and acquire holiness in the fear of God. Work, wear yourself out, in order to acquire humility, whereby you will become the heir of everlasting goods. Put off pride and the shamelessness of worldly habits. Practice obedience toward all. Perform the duties that are imposed upon you without complaint. Be enduring in prayer. Be neither lazy nor sleepy during the vigils. Steadfastly resist temptations. Be not neglectful of your fasts, but know that prayer and fasting are the way to win favor with God.... Henceforth nothing must matter to you but God. You shall love neither father nor mother nor brothers, nor any in your family. You shall not love yourself more than God.... Nothing shall restrain you from following Christ.... You will have to suffer, you will go hungry, you will endure thirst, you will be robbed of your clothing, you will suffer injustice, you will be mocked, you will be persecuted, you will be slandered, you will be visited by many bitter tribulations — all these sufferings are the token of a life in keeping with the will of God.” Naturally, ideal and reality are often at odds. But even in times of decadence Eastern monasticism has repeatedly attained great heights. It is not out of the question that the present era of an apparently total decay of Orthodox monasticism will be followed by an age of renewal and practical realization of a time-honored ideal.

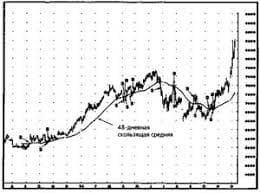

ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|