|

|

Christian Influences at the Court of the Mongol Khans.The medieval West had highly exaggerated views of the Christian sympathies of the Mongol khans. The reason for this was the fact that the bitterest enemies of the Mongol Empire in West Asia were Muslims. In Western eyes the central citadel of Islam was Mamluk Egypt, which the Mongols had so frequently fought but never conquered. Because the Christians were enemies of Islam, the Mongol viceroys of Persia, the ilkhans, showed them favor. Three Persian viceroys had been baptized as Christians in their childhood; several of them had Christian wives who exerted a rather considerable influence upon them; and for a time the Mongols seemed to be balanced so precariously between Islam and Christianity that it appeared as though the lightest touch might sway the decision. The West regarded the Mongol khans as to some extent the successors of the mysterious Prester John, the legendary great Christian priest-king of the Far East. The pious legends and prophecies of the West revolved about the hope that Prester John would overrun the lands of Islam from the east while the crusaders attacked them from the west. We possess an account of the religious tolerance of Great Khan Mangu from the pen of William of Rubruck, a Flemish Franciscan monk who in 1253 was sent by Louis IX of France to the court of the Great Khan in Karakorum. William relates that the Great Khan organized religious discussions among representatives of western Christianity, Buddhism and Nestorianism. And Mangu Khan himself attended Nestorian services, although he had not been baptized. Thus there took place under the Mongols a moderate revival of that Nestorian Christianity that had flourished in China during the Tang dynasty and then had almost completely disappeared. In 1275 a Nestorian metropolitan was installed in Cambaluc, as Peking was known in medieval times. Nestorian Christians became so numerous and widely disseminated in the Mongol Empire that Kublai Khan in 1289 set up a special board, a kind of ministry of church affairs, especially for them. By 1330 the Archbishop of Soltania was reporting that there were more than 30,000 Nestorians in Cathay, and that they “were wealthy, with many handsome and richly decorated churches and crosses and images in honor of God and his saints. They held special divine services in the presence of the Emperor and had been granted great privileges by him.” Chinkiang was one center of the Nestorians. There and in the vicinity Mar Sergius (Sargis), a physician from Samarkand who served as governor of the city in 1277-78, founded seven monasteries. At the beginning of the fourteenth century there were three Nestorian churches in Yangchow; one of them, the Church of the Cross, had been founded by a rich Nestorian merchant named Abraham at the end of the thirteenth century.

VIII. Orthodox Culture.

The Orthodox Culture. S ince the Orthodox religion profoundly affects the believer in his practical and intellectual attitudes toward God, his fellowmen and nature, it is obvious that an Orthodox has emerged from the Orthodox faith. Unfortunately there has so far been no comprehensive account of this Orthodox culture, in all the diversity of its forms, among the various Orthodox peoples of Greek, Slavic and Asiatic tongues. While the various types of thought and the social and cultural manifestations of the Western forms of Christianity have been the subject of scholarly examination — especially in the works of Ernst Troeltsch and Max Weber — similar studies of the Orthodox Church have been undertaken only with regard to Byzantine culture by Louis Brйhier, and those were confined to the Church of the Duchy of Kiev and the old Duchy of Moscow up to 1459. Yet the specific forms of Orthodox culture are much more obvious and much easier to identify than, say, the forms of Protestant culture, which very frequently appear in the guise of elusive, purely psychological and concretely not only in philosophy, literature and art, but also in habits of life and forms of community organization — down even to such matters as the peculiarly Orthodox cuisine. We can only suggest the bare outlines of Orthodox culture here. In both the Byzantine Empire and the old schismatic churches of Asia and Africa three areas of art do not fall within the sphere of Orthodox culture. These are: sculpture, the theater, and instrumental music for the Church. To compensate for these exceptions, however, other branches of art have been brought to an extraordinarily high development.

The Absence of Sculpture from Ecclesiastical Art. The absence of sculpture is due to a prohibition of its use in ecclesiastical art which — as we have shown in Chapter I — is connected with the theological conception of the nature of icons. The celestial archetypes are reflected only in the two-dimensional surfaces of icons (see p. 6). So strong have been the influence of the antisculptural spirit of Byzantine ecclesiastical painting and the effects of the iconoclastic controversy that Byzantine culture has never even developed secular sculpture. Sculpture has developed only in miniature art; but even there it has been confined largely to the art of relief, often an extremely shallow relief that in effect was scarcely removed from the two dimensionality of the icons. The ancient ecclesiastical art of ivory carving was practiced to a considerably greater extent. In the age of Justinian and the period immediately following single or double and triple foldable ivory tablets (diptychs and triptychs), and ivory boxes (pyxides) of classical beauty were produced; and in the Middle Ages also icons on single tablets of ivory, or diptychs and triptychs representing saints or Biblical motifs, were made in large numbers. There were also boxes, chests and bowls made for secular purposes but carved with ecclesiastical motifs. This type of art took root throughout the whole area under the influence of the Orthodox Church, not only in Asia Minor but also in the East and South Slavic lands. To supply the demand for liturgical vessels, a goldsmith's art of remarkable beauty grew up on Orthodox soil. To further embellish their creations, the goldsmiths early borrowed the Persian technique of enameling. The popular art of enameled metalwork, which was especially esteemed in Russia, was a direct outgrowth of this technique.

Icon Painting and Mosaics. The restriction of ecclesiastical art to two-dimensional painting had its positive aspect. It led to a great flowering of icon painting, to mural painting on the grandest scale, and above all to magnificent mosaic art. Christian mosaic art, of course, started from the base laid down by classical antiquity's approach to form and nature; but by abstract stylization according to intellectual and religious dictates, by abolishing realism and the illusion of space, an entirely new style was created. Ultimately all suggestion of space was either eliminated or only sketchily implied, and sculptural rounding of bodies shunned as far as possible; where a sense of space was suggested at all, the perspective was inverted, the focus of the lines not being in the eye of the observer, but at some transcendent point behind the picture — shifted, as it were, to the divine eye. The spatial lines ran from the observer back to this transcendental center; from this inverted, divine perspective, the human persons in the foreground of the picture were rendered smaller than the figures of the saints who, being closer to God, occupied the greater part of the icon's surface. As it happens, works of Byzantine mosaic art and mural paintings are now to be found almost exclusively in the West, largely in Ravenna and the Byzantine churches of Sicily. In the East they were mostly destroyed by the barbarous iconoclasts. A large number of mosaics, especially in the Balkans, were coated with whitewash by the Turkish conquerors of those regions. Some few escaped that fate, including the mosaics of the monastery church on Sinai (sixth century), the Churches of St. George (fifth century) and St. Demetrius (sixth to tenth centuries) in Salonika, the mosaics of Aya Sophia in Salonika (ninth century) and the earliest mosaics of the Koimesis church in Nicaea (presumably from the seventh century). Splendid examples of early medieval Byzantine mosaics are to be seen in Hosios Lukas in Stiris, in Nea Moni on Chios, in the monastic church of Daphni near Athens, and in the Kahriyeh Jamissi in Constantinople. In the West there are great mosaics in San Marco in Venice, in the Martorana in Palermo, and in the Cathedrals of Cefalщ and Monreale. On Slavic soil, mosaic works of the eleventh century are preserved in the Churches of St. Sophia and St. Michael in Kiev.

Mural Painting. The iconoclasts of the eighth and ninth centuries wreaked even greater havoc upon mural painting. Nevertheless considerable series of murals have survived in the almost inaccessible cave churches of monks and eremites, who were in any case the firmest advocates of the veneration of images and often defended themselves against the iconoclasts by force of arms. Thus paintings on Latmos near Herakleia and especially in the numerous cave churches of Cappadocia, near Gцreme and Ьrgьb (ninth to eleventh centuries), escaped destruction. In the West the remains of frescoes in St. Saba in Rome (tenth century) and the great cycle of frescoes of St. Angelo in Formis near Capua (eleventh century) convey an impression of the grandeur of this mural painting. There are also mural paintings in Novgorod (twelfth century), in Mirosh near Pskov (twelfth century) and in the Church of the Redeemer at Neredichy (c. 1200). The art of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries is especially well represented. There are, for instance, the extensive series of paintings in the churches of Mistra and in a number of monasteries on Athos, as well as in many Serbian, Macedonian and Romanian monasteries. Strong Cretan influences are evident in these latter. Cretan icon and mural painting exerted an indirect influence upon the baroque art of the West in the seventeenth century, for the Greek painter Domenicos Theotocopoulos, known to the West as El Greco, carried thither the traditions of the icon and mural painting of his native Crete. Careful restoration projects by art experts in the past few decades have uncovered a goodly number of the Byzantine mosaics and murals which the Turks had attempted to bury beneath coats of whitewash and plaster. The results of such restoration in Salonika make us once more aware of the overwhelming variety and splendor of Byzantine art. In fact Salonika with its multitude of churches of many periods is the best place to visit if we would form some conception of the whole span of Byzantine art from the fifth to the fourteenth centuries. There are also the many churches in Berrhoea in Greek Macedonia whose art has likewise been revealed once more. The most staggering sight of all, however, is afforded by the resurrected mosaics of the greatest miracle of Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture, Hagia Sophia, the heart of the Byzantine Church. The great church was transformed into a mosque after the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. At last, under the enlightened rule of Kemal Pasha, the edifice was made a Turkish national museum and the mosaics of the dome, dating from the golden age of Byzantine supremacy that followed on the end of the iconoclastic struggle, now glow once more in their original beauty.

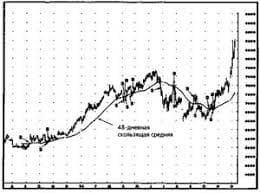

ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|