|

|

Metallic Adornment of Icons.The art of icon painting was to some degree the loser when the custom arose — especially in Slavic countries — of expressing veneration for the sacred image by embellishing it with costly metals and gems. Thus the icons are frequently coated with gold leaf or hammered silver, with the outlines of the holy figures incised or pricked into the rich ground, only their hands and faces being painted. Other metals, such as bronze, copper and tin, might be used, or else the icon might be made of a plaque of wood into which the sacred figures were carved. Enameling was also greatly favored. Through the dissemination of icons in every house, from mansion to hovel, these art forms of the Orthodox Church have had the most enormous influence upon the aesthetic feelings of the Orthodox populace.

Illumination. Alongside of icon and mural painting there was also the flourishing art of illumination. Theologians and monks read the Fathers of the Church in richly ornamented manuscripts; priests and choir studied beautifully illuminated copies of the liturgy. Fostered by generous commissions from the emperors and numerous donors, illumination developed into an art of the greatest magnificence throughout the whole territory of the Orthodox Church. The treasuries of the monasteries on Athos and Mount Sinai, which have only recently been opened to inspection, are filled with gloriously embellished manuscripts of psalters, liturgical documents and writings of the Fathers.

Minor Arts and Crafts. The minor arts and crafts were also brought to a high peak of perfection in Byzantium. Much of both Arabian craftsmanship and that of the West stem from this source. The West is particularly indebted to Byzantium for two important crafts. The first of these is the art of pouring bronze, a classical technique that was kept alive in the Byzantine Empire. Bronze doors, baptismal fonts and bowls of great artistic value were produced; and in the eleventh and twelfth centuries the technique was transplanted to Sicily and southern Italy (Amalfi). Byzantine bronzes manifested the characteristic Eastern tendency to stress two dimensionality in sacred images. An equally important craft was that of silk weaving, which took over the images and stylistic motifs of icon painting and developed these into an independent art. The weavers wrought veritable miracles in the production of altar cloths and liturgical robes. Similarly in Ethiopia, Georgia, Armenia and Egypt the rug makers borrowed images and stylistic motifs from icon painting. Carolingian art found its inspiration in the whole compass of Byzantine art, from icon and mural painting to illumination and the designing of liturgical robes (consider the dalmatic of Charlemagne in St. Peter's in Rome). The Arabian crafts that spread out over the Iberian Peninsula were also strongly affected both in their techniques and in their styles by Byzantine examples. Arabian illumination plainly reveals such influences. In fact, as Frobenius has shown, Byzantine art left its stamp as far south as the Nubian cultures of central Africa.

Flourishing of Liturgy. T he early Christians regarded the theater as a spawning ground of pagan ideas. Tragedy as a rule dealt with the myths of the old gods; comedy represented licentiousness in all its forms. Almost all the great Fathers of the Church condemned the theater in their sermons and writings and endeavored to keep Christians from attending it. A distaste for theater as a resort of demons, idolatry and lewdness became deeply rooted in the Church. The older Church ordinances — particularly in Egypt — listed the profession of actor together with that of brothel keeper, judge and soldier among the occupations that a man must abandon if he wished to receive baptism. Consequently there was never any chance for theater to develop in the area of Byzantine culture. Not until the eleventh century was any Christian drama attempted: The Suffering Christ, an enactment of the Passion. But this effort was not intended for the stage; it was a crude literary construct, a so-called cento, that is, a play composed of verses and fragments of verses pieced together out of classical tragedy. Such erudite pastiches can scarcely be regarded as the rebirth of tragedy in the Byzantine Empire. In compensation for the extinction of classical drama, an extraordinary wealth of liturgy developed in the Church. This liturgy is a highly animated mystery play, with various entrances and processions and responsive choruses. Each particular church could give its own turn to these mystery dramas, since for a long time there were no curbs on improvisation. It was not until the nineteenth century that a native secular drama finally appeared, and then it was only in the western Orthodox countries, primarily in Russia, which were receptive to current Western literary influences. Otherwise, ecclesiastical tradition almost completely suppressed the birth of secular drama. On the other hand, the essentially dramatic nature of the liturgy led to the continual creation of a host of new forms; the original character of the liturgy as charismatic improvisation went on exerting a creative influence even after the form of the liturgy itself had been more or less frozen by the imposing of uniform patterns upon the whole of the Byzantine state Church. In the various churches of Byzantium the sermon became a kind of dramatized homily. That is to say, the commentary on particular Gospel texts was enlivened by insertion of dialogues, little scenes, monologues and choruses. Various episodes out of the Bible were incorporated into the general mystery drama of the liturgy. There would be, for example, an enactment of the baptism of Jesus, of the childhood of Mary, of the Annunciation, of the conspiracy of the demons against Christ, of the birth of Christ, of the flight to Egypt, or of Christ's harrowing of hell. These dramatic representations were closely linked with particular church festivals; they were inserted amid the rituals of the feast day; and the actors were not laymen, but clerics, usually the same priests and deacons who celebrated the liturgy. In Byzantium, religious drama was never allowed to drift away from its liturgical, ecclesiastical origins.

Ascendancy of Choral Singing.

The Dogmatic Justification. The Orthodox Church excluded instrumental music from its observances: Man must not employ lifeless metals and lifeless wood to praise God. Rather, he himself should be the living instrument for the praise of God. He should not delegate his Christian task to flutes, trumpets and organs, but should glorify God with his own lips as also with his whole life. One important reason for this rejection of instrumental music was the fact that certain pagan mystery cults employed music to intensify the orgiastic mood of their rites. Consequently the Church held aloof from this music as representing a pagan form of worship, just as it did from the pagan theater. Thus, instrumental music in the Byzantine Empire was restricted to secular celebrations. Small portable organs were played at court festivals and in the circus, but not in church.

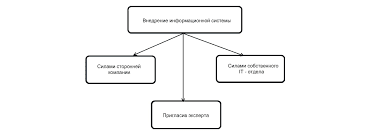

Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|