|

|

Relationship to the Anglican Church.⇐ ПредыдущаяСтр 23 из 23 Orthodoxy's relations with the independent Protestant churches of England and North America have been darkened by the fact that these churches conducted missions in the territory of the Orthodox national churches of Greece, the Near East and Egypt and tried to make converts even among the Orthodox. Nevertheless, there were early Orthodox efforts toward rapprochement with the Anglican Church, and in some cases these led to shared communion. The roots of this amity go back to the eighteenth century. Fresh efforts were made in the thirties and forties of the nineteenth century, as a result of the emergence of the High Church movement in Oxford, which stressed acceptance of episcopal organization and apostolic succession as the dogmatic basis of catholicity. Ever since, discussion has centered primarily upon the question of the Eastern Orthodox Church's recognition of Anglican ordinations. In the course of this debate the two churches moved closer together or farther apart according to the vagaries of national and ecclesiastical policy within the complicated structure of the British Empire. However much the two churches might disagree on dogma, a cordial feeling prevailed. For one thing, the Anglican Church did not attempt to proselytize among Orthodox believers when these came within its scope, as they so often did, England being the occupying power not only in the Near East but also in India. Hence Anglicans were constantly thrown into contact with members of Orthodox national churches in large portions of the world, and on the whole got on well with them. In 1841 an Anglo-Prussian episcopate was established in Jerusalem, with its bishop ordained according to the Anglican rite. This Jerusalem diocese included all the Protestants of the Holy Land. When it was set up, it explicitly acknowledged the traditional rights of the old Orthodox episcopates and patriarchates and pledged itself to refrain from missionary activity among Orthodox Christians.

Oppositions to the ecumenical movement. One cannot ignore the currents within the Orthodox Church and the arguments that opponents have raised to the Church's involving herself with the World Council of Churches. Political factors play a large part in this opposition. Such factors, for example, were clearly present in the decision of the Moscow Synod of 1948, whose sharp repudiation of the ecumenical movement and rejection of the overtures of the Anglican Church was entirely in the spirit of the foreign policy. There are also the serious objections raised by those who point out that in entering the ecumenical movement the Orthodox Church is instituting amicable relations with the very churches that have hitherto regarded the Orthodox lands as a missionary field and have sometimes behaved quite ruthlessly in this respect. Even where the pressure of proselytism has abated or where it has been deliberately eschewed, such modern Christian world youth organizations as the YMCA, YWCA and the World Student Christian Federation (WSCF), whose attitudes are fundamentally ecumenical, are suspected of Protestant missionary aims. Many conservative members of the Orthodox Church regard these organizations as Trojan horses that have been brought within the walls of Orthodoxy in the name of the Universal Church, but which in reality contain armed bands of Protestant missionaries. Moreover, these ecumenical organizations, which exert a strong attraction upon the Orthodox youth of the Near East and Egypt, are fundamentally liberal in theology. To the eyes of many Orthodox conservatives they are a form of Freemasonry in Christian camouflage. Conservative Orthodox circles often express the same doubts about the World Council of Churches, which includes many denominations whose dogmas are miles apart from the tenets of the Orthodox faith. Moreover, many members of the churches of Asia Minor, Egypt and Ethiopia regard the non-Orthodox forms of Christianity primarily as the religions of their former occupation powers or colonial masters, to whose dominion they were exposed for centuries. When new YMCA centers are built in Orthodox cities of the Near East, the people tend to look upon the matter as merely another offshoot of drilling for oil, on a par with the establishment of new refineries, pipelines and airports. In the field of dogma, too, there are theologians who would prefer a strictly exclusive attitude toward Orthodox doctrines. They feel that the Orthodox cause is being betrayed if Orthodox theologians as much as engage in a discussion about the principles of the faith with the neo-Orthodoxy. Even those theologians who are ready to participate in ecumenical work complain that the Apostolic purity of its faith of Orthodoxy is not taken seriously within the ecumenical movement. However, the Protestant churches find it wonderfully rewarding to join in theological efforts with churches that have preserved the doctrinal and liturgical traditions of the primitive Church through centuries of the severest persecution and tribulation. Such churches have retained a continuity of views and types of worship that churches of the modern Western type might easily come to dismiss as outmoded. A closer knowledge of the character of the Eastern Church, however, corrects this tendency. On the other hand, it is of the greatest importance to the Orthodox Church, whose intellectual development has been handicapped by centuries of repression under non-Christian and deliberately anti-Christian forces, to engage in a vital confrontation with types of Christian ecclesiasticism that have attempted, under more favorable conditions, to assimilate all the political, social, technological and cultural trends of modern times and to find new forms of community living and education.

XIV. Greatness and Weakness of Orthodoxy.

The Strength of Orthodoxy. W ithin contemporary Christendom, Orthodoxy shines with a light all its own. Especially impressive is the fact that it has preserved faithfully the catholicity of the primitive Church. This is true for all its vital functions. Its liturgy is a wonderful repository of all the early Church's interpretations and practices of worship. Whatever the early Church and the Byzantine Church created in the way of liturgical drama, meditation and contemplation, in beauty of prayers and hymns, has been integrated and retained in the Orthodox liturgy. Similarly the content of Scripture has been kept ever present in the form of generous readings from both the Old and the New Testaments at various prescribed times through the liturgical year. The entire historical tradition of the Church is constantly communicated to the members in readings from the lives of the great saints and mystics (see p. 27 ff.). The sermon has its fixed place in the sacramental service; originally it came immediately after the reading of the Gospel text in the service for catechumens, but nowadays it frequently comes elsewhere, for example, after Communion. Verbal service and sacramental service are meaningfully interlocked so that total separation of them, such as has occurred in Western Reformed churches, can never occur. The full doctrine of the early Church, as it was defined by the seven ecumenical councils, is immediate and vital in the liturgy, and also in the hymn of worship that elaborates the fundamental ideas of both Orthodox and lay prayer. Here there is no divorce between liturgy and theology, worship and dogma. This Church has clung to the original consciousness of universality and catholicity. Its sense of itself as the one holy, ecumenical and apostolic Church is based not upon a judicial idea, but upon the consciousness of representing the Mystical Body of Christ. According to the Orthodox outlook, the celestial and the earthly Church, and the Church of the dead, belong indissolubly together. In taking part in the liturgy the earthly Church is reminded that it belongs to the higher Church. In the liturgy the earthly congregation experiences the presence of the angels, patriarchs, prophets, apostles, martyrs, saints and all the redeemed; in the sacrament of the Eucharist it experiences the Presence of its Lord. Within the Mystical Body there takes place a unique communication and correlation: within that communion the gifts of the Holy Spirit — the power to forgive sins, to transmit salvation, to suffer by proxy for one another, and the power of intercession — become effective. And these powers extend down to the domain of the dead, for God is “a Lord of the living, not the dead.” In this way the Church has preserved the early Christian combination of genuine personalism, of appreciation for the uniqueness and singularity of the individual, along with the early Christian sense of communion. But the catholicity of the Orthodox Church is not in any way synonymous with uniformity. Thanks to its principle of letting every people possess the gospel, liturgy and doctrine in its own language, Orthodoxy has been able to adapt to the natural national differences within mankind. The broad framework of Orthodoxy has been able to accommodate a wealth of ecclesiastical traditions. The result has been that the Orthodox Church has shown itself as an extraordinarily creative force. It has exerted great religious, social and ethical influence upon the cultures of Orthodox nations and taken a leading part in the intellectual and political development of those nations. This function of the Orthodox Church has been especially significant during the periods in which the political existence of Orthodox nations was threatened or destroyed. Orthodoxy's unity within variety has been sustained by a unified canon of the New and Old Testaments, by a unified episcopal organization based on apostolic succession, by a unified liturgy that is the same in all languages, and by unity of doctrine and dogmatic tradition. The durability of the Orthodox Church is all the more remarkable in that it has been exposed to enormous historical disasters, to persecutions of all kinds, especially from Islam; in great stretches of its former dominions, Orthodoxy has been completely exterminated. Nevertheless it has adhered with the greatest loyalty, down to the present day, to the early Church's liturgical and dogmatic heritage. This heritage is not at all a museum piece as has often been asserted. On the contrary, it is a living force capable of development. In a certain sense the greatness of Orthodoxy rests on the very fact that the doctrine is not so carefully defined down to details, is not so strictly regulated by canons. Orthodoxy's system is by no means closed; it is still full of potential. The charismatic life of Orthodoxy has not been confined within sets of legal and institutional forms. There is a significant degree of intellectual mobility, even in theology; thus, teachers of theology are frequently laymen rather than ordained priests. Alongside the offices of deacon, priest and bishop, the Church has from the beginning left room for the office of the teacher — didaskalos. A further essential trait of the Orthodox Church is Christian universalism. This manifests itself in Orthodoxy's view of the cosmos as well as its view of history. Western Christianity has more or less underplayed the question of a Christian natural philosophy. The Eastern Church, on the other hand, has endeavored to frame its Christian interpretation of creation in an unending series of sketches for a Christian cosmology and natural philosophy. It views the process of redemption not only as an event that has taken place for the benefit of man, within the framework of human history, but also as a cosmic event in which the evolution of the entire universe is included. Anthropology, cosmology and the doctrine of salvation are indissolubly interconnected. According to the Orthodox theory, the fall of man carried along the entire universe into rebellion against God, exposing everything to the powers of sin and death. Similarly, the incarnation of God in Jesus Christ and his resurrection likewise had cosmic effects. The “whole of creation” participated in the salvation brought by Christ, and all creatures yearn for the day of redemption along with man. Thus, at the end of time, when salvation is fulfilled, the old earth and the old heaven will be transformed along with man into a new earth and a new heaven. The reshaping of creation will involve the entire universe. This universalism is also magnificently present in the Church's interpretation of redemption. It does not restrict the effects of divine redemption to the narrow confines traditionally promised by the Old Testament. According to the Orthodox Church, it is not only the Chosen People, but all the peoples of the globe who are involved in the story of man's redemption. The universalism of Orthodox thought is based upon the doctrine of the Logos. Orthodox theologians grant that the divine Logos spoke chiefly through the voices of the Old Testament prophets before the Incarnation, but there are evidences of his presence among other peoples. Another element making for the greatness of Orthodoxy is its unwavering emphasis on the idea of God's beauty. Its prayers and hymns have never ceased to praise the beauty of God. This picture of God does not accord with the picture of a wrathful God of justice and predestination as has been painted by Occidental theology. It can only be tenable if paired with a universalism that sees Christ as the perfector of the cosmos and of salvation, as the conqueror not only of sin but also of physical annihilation, as the victor over death and the demonic powers of the entire cosmos. In consequence, Orthodoxy has preserved the original mood of the Christian fellowships, the chara — rejoicing and jubilation — which the New Testament mentions as the characteristic spirit of the first Christian fellowship. This rejoicing has remained the fundamental mood of divine service in the Orthodox Church, especially of the Eucharistic service: joy in union with the living Lord; jubilation that the powers of sin and death have been overcome, the demons defeated, and that the reign of Satan has already been shattered. Its basic assumption is that at bottom evil is already overcome, that to the reborn the new eon of life in God, of glory in God and the beauty of God, the life of new creatures in a new cosmos, has already dawned.

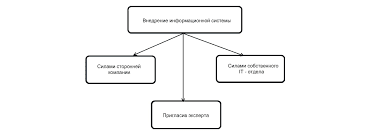

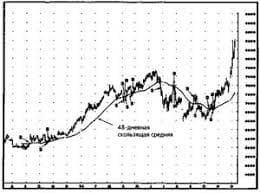

Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры...  Что способствует осуществлению желаний? Стопроцентная, непоколебимая уверенность в своем...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|