|

|

Russia as the Savior of Europe in the Napoleonic Wars.During the dramatic years of the Napoleonic wars the belief arose on Russian soil that the Russian Empire was not just an ordinary part of Europe, but the godsend, destined savior of Europe. Tsar Alexander I enthusiastically promoted the conception of the Holy Alliance: the three great rulers of Europe, who also represented the three great Christian confessions (Orthodox Russia under Alexander I, Protestant Prussia under Frederick William III and Catholic Austria under Francis I) were uniting to save Europe from the Antichrist who threatened them from the West. The allegory was borne out by the eventual victory of the Russian army over Napoleon, a redemption that was purchased at the price of burning “Holy” Moscow.

The Burning of Moscow. From the very start the Russian people injected religious meaning into the War of 1812. The burning of Moscow seemed to them a great self-immolation Holy Russia was making in behalf of all Europe in order to break the power of the hitherto invincible Antichrist. At a time of deep misfortune the people saw in the burning of Moscow the manifestation of God's saving mercy. This religious note is likewise sounded in Tsar Alexander's proclamation of thanksgiving: “He who guides the destinies of nations, Almighty God, has chosen the venerable capital of Russia to save, through her sufferings, not Russia alone, but all of Europe. Her fire was the conflagration of freedom for all the kingdoms of the earth. Out of the offences against her Holy Church sprang the victory of Faith. The Kremlin, undermined by evil, crushed in its fall the chief of the evildoers.” In similar terms Alexander addressed Bishop Eilert, a Protestant, in Berlin: “The burning of Moscow has illuminated my soul. The judgment of the Lord upon the ice-covered fields has filled my heart with the warmth of Faith.... Now I am coming to know God. Since that time I have been a changed man. I owe my own redemption and liberation to the salvation of Europe from ruin.” The sense of belonging to Europe was founded upon the idea of unity of the Christian main Christian believes of Europe. France, once the principal power of Europe and now revolutionary and atheistic, was manifesting itself as the great betrayer of the idea of a Christian Europe, whereas Russia had emerged as the instrument chosen by God to save European Christendom.

The Slavophiles. Those theoreticians who treasure the idea of an unbridgeable gulf existing between Russia and Europe are fond of citing the historical views and cultural philosophy of the Slavophiles. Here were representative figures of Russian Orthodoxy, they point out, who themselves were of the opinion that such a gulf existed between Russia and the “rotten West.” It is true that a large number of quotations can be garnered from the writings of Ivan Kireevsky, Constantine and Ivan Aksakov and Yury Samarin, in which much is made of the contrasts between Russia and the West, these contrasts being attributed to the Orthodox character of Russia. They repeat the stereotyped claim that Russia is the carrier of Orthodox “truth” (pravda), and argue that the inner degeneracy of the West is due to Roman Catholicism. We should not be misled, however, into seeing these Slavophile doctrines as proof of a real dichotomy between Russia and Europe. Interestingly enough, the Slavophiles set forth their criticisms of the West in a periodical called The European, which Ivan Kireevsky began publishing in 1832. Even the most radical of the Slavophiles did not consider the “rotten West” to be synonymous with Europe, nor were they suggesting that Russia ought to exclude herself from Europe. The origin and descent of their ideas are highly significant. The ideology of the Slavophiles was rooted most strongly in German romanticism and in German idealistic philosophy, chiefly the philosophies of Hegel, Schelling and Franz von Baader. It can be traced further back to the ideas of Herder. In its themes and its viewpoint, Slavophile theory moved completely within a European framework. The Slavophiles were, in fact, one more of those groups of romantic intellectuals who emerged in various European countries during the nineteenth century, most conspicuously in Germany. Their nationalism too was a specifically romantic trait, and even the messianism generally considered so characteristic of the Slavophiles displayed features that could be found among other romantic groups in various countries of Europe. Thus the Slavophiles scarcely serve as “proof” that Russia belongs to Asia rather than Europe. They actually show that the intellectual, religious and philosophical development of Russia was consistent with the general development of Europe. Russian Slavophilism with its offshoots of nationalism and messianism. represents only a variant of the romantic nationalism of Germany or England. The Slavophiles' criticism of the “rotten West” was for the most part identical, even to details, with German romanticists' criticism of the French Enlightenment, of aspects of the French Revolution, and of the first glimmerings of modern technical and materialistic thinking. Yet no historian would ever dream of calling German romanticism an Asiatic phenomenon. Nor did the Russian Slavophiles ever carry their polemics against the West to the point of assigning Russia and themselves to Asia rather than Europe. For them too Russia always remained a part of the Christian European world. And although they distinguished Russia, as the “East,” from the “Latinism” of the West, Russia remained in their eyes “Western” and “European” in relation to Asia. This is true above all for Dostoevsky, who never ceased to refer to himself as a “Russian European,” and who repeatedly declared: “We cannot give up Europe.” “Only the Russian, even in our time, which is to say, long before the general balance has been drawn up, only the Russian has been given the capacity to be most Russian when he is most European.”

The Crimean War as “Europe's Betrayal of Russia.” The Crimean War severely shook Russia's sense of fellowship with Europe. This intellectual crisis was, however, brought about not by Russia, but by Catholic circles in France. There was a significant difference between the German and the French attitudes toward Russia during the Crimean War. Prussia felt that at bottom she was still linked with Russia by the Holy Alliance. In the debates on the Crimean War held in the Prussian parliament, Friedrich Julius Stahl, the conservative theologian and student of canon law, insisted that the Holy Alliance was nothing but the modern continuation of the old idea of the Roman Empire and of the Christian solidarity of the nations included within that Empire. This tells us something of the extent to which Russia was regarded by the Prussians as a natural member of the Christian and European community of nations. France took an altogether different view. France's participation in the Crimean War was expressly sanctioned by the Archbishop of Paris. In a pastoral letter he described the war as a crusade against the “heresy of Photius.” He was reviving the ancient anti-Orthodox position of the Roman Catholic West, for during the Middle Ages the Roman Catholic Church had proclaimed the struggle against Byzantium to be one branch of the crusade against Islam. No wonder that the Russians felt that the West was banding against her and no wonder the Slavophiles denounced France and England for betraying her. Yet not even this experience could extinguish the Russian sense of belonging to Christian Europe. That is plainly to be seen in the work of so distinguished a thinker as Vladimir Soloviev. One of Soloviev's favorite ideas was that the Christian world could only resist the onslaught of non-Christian Asia if it clung to the ideal of its unity. If the Christian world, including Russia, were ever to turn away from this idea, he contended, the non-Christian Far East would inevitably bring about the 'downfall of Europe. If the Occident forgot its mission as the pillar of Christian culture, it would succumb to Asia. In Soloviev's eschatology, the bankruptcy of the Occident was bound up with the end of history. In his famous Three Conversations written in 1899-1900,[11] he painted a picture of the last war in history, which he predicted would take place in the twentieth century: the struggle of Europe against a pagan Asia united under the banner of pan Mongolism. In this vision of the future, France was pictured as the betrayer of Christian solidarity-bearing out Russia's interpretation of the French attitude in the Crimean War. Soloviev envisioned France as joining in an alliance with the Mongol invaders to save her own skin, and so furthering the Mongols' rapid conquest of the rest of Europe. Russia's sense of being the bulwark of Europe awoke once more in a new fashion, in what we may call a final, wholly secularized form, at the time of the Russo-Japanese War. Once more Russia saw herself as the representative of Europe opposing the political power of rising Asia, the “yellow peril” as embodied in Japan. The Russians felt this all the more keenly because Russia was abandoned by the European powers in this struggle; they saw themselves betrayed and ridiculed and took their defeat in the war as an ominous sign of future victories of the Asiatics over Europe. A feeling of genuine solidarity with Christian Europe has been present throughout Russian history. It has not just cropped up occasionally as a passing fad, but has been actively present as a creative intellectual and political principle. There have been, however, a number of counter forces to this sense of solidarity with Europe, and these forces have produced an ambivalent attitude toward Europe.

Dividing Factors.

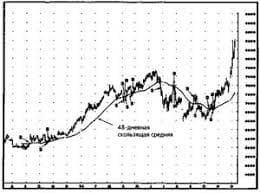

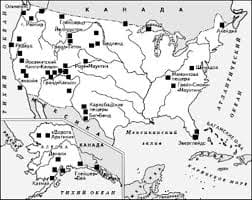

Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|