|

|

Organization and Training of the Jesuits.Loyola’s Vast Schemes — A General for the Army — Loyola Elected — ”Constitutions” — Made Known to only a Select Few — Powers of the General — An Autocrat — He only can make Laws — Appoints all Officers, etc. — Organization — Six Grand Divisions — Thirty-seven Provinces — Houses, Colleges, Missions, etc. — Reports to the General — His Eye Surveys the World — Organization — Preparatory Ordeal — Four Classes — Novitiates — Second Novitiate — Its Rigorous Training — The Indifferents — The Scholars — The Coadjutors — The Professed — Their Oath — Their Obedience.

THE long-delayed wishes of Loyola had been realized, and his efforts, abortive in the past, had now at length been crowned with success. The Papal bull had given formal existence to the order, what Christhad done in heaven his Vicar had ratified on the earth. But Loyola was too wise to think that all had been accomplished; he knew that he was only at the beginning of his labors. In the little band around him he saw but the nucleus of an army that would multiply and expand till one day it should be as the stars in multitude, and bear the standard of victory to every land on earth. The gates of the East were meanwhile closed against him; but the Western world would not always set limits to the triumphs of his spiritual arms. He would yet subjugate both hemispheres, and extend the dominion of Rome from the rising to the setting sun. Such were the schemes that Loyola, who hid under his mendicant’s cloak an ambition vast as Alexander’s, was at that moment revolving. Assembling his comrades one day about this time, he addressed them, his biographer Bouhours tells us, in a long speech, saying, “Ought we not to conclude that we are called to win to God, not only a single nation, a single country, but all nations, all the kingdoms of the world?” 1 An army to conquer the world, Loyola was forming. But he knew that nothing is stronger than its weakest part, and therefore the soundness of every link, the thorough discipline and tried fidelity of every soldier in this mighty host was with him an essential point. That could be secured only by making each individual, before enrolling himself, pass through an ordeal that should sift, and try, and harden him to the utmost. But first the Company of Jesus had to elect a head. The dignity was offered to Loyola. He modestly declined the post, as Julius Caesar did the diadem. After four days spent in prayer and penance, his disciples returned and humbly supplicated him to be their chief. Ignatius, viewing this as an intimation of the will of God, consented. He was the first General of the order. Few royal scepter's bring with them such an amount of real power as this election bestowed on Loyola. The day would come when the tiara itself would bow before that yet mightier authority which was represented by the cap of the General of the Jesuits. The second step was to frame the “Constitutions” of the society. In this labor Loyola accepted the aid of Lainez, the ablest of his converts. Seeing it was at God’s command that Ignatius had planted the tree of Jesuitism in the spiritual vineyard, it was to be expected that the Constitutions of the Company would proceed from the same high source. The Constitutions were declared to be a revelation from God, the inspiration of the Holy Spirit.2 This gave them absolute authority over the members, and paved the way for the substitution of the Constitution and canons of the Society of Jesus in the room of Christianity itself. These canons and Instructions were not published: they were not communicated to all the members of the society even; they were made known to a few only — in all their extent to a very few. They took care to print them in their own college at Rome, or in their college at Prague; and if it happened that they were printed elsewhere, they secured and destroyed the edition. “I cannot discover,” says M. de la Chalotais, “that the Constitutions of the Jesuits have ever been seen or examined by any tribunal whatsoever, secular or ecclesiastic; by any sovereign — not even by the Court of Chancery of Prague, when permission was asked to print them... They have taken all sorts of precautions to keep them a secret.3 For a century they were concealed from the knowledge of the world; and it was an accident which at last dragged them into the light from the darkness in which they had so long been buried. It is not easy, perhaps it is not possible, to say what number of volumes the Constitutions of the Jesuits form. M. Louis Rene de la Chalotais, Procurator-General of King Louis XV., in his Report on the Constitutions of the Jesuits’, given in to the Parliament of Bretagne, speaks of fifty volumes folio. That was in the year 1761, or 221 years after the founding of the order. This code, then enormous, must be greatly more so now, seeing every bull and brief of the Pope addressed to the society, every edict of its General, is so much more added to a legislation that is continually augmenting. We doubt whether any member of the order is found bold enough to undertake a complete study of them, or ingenious enough to reconcile all their contradictions and inconsistencies. Prudently abstaining from venturing into a labyrinth from which he may never emerge, he simply asks, not what do the Constitutions say, but what does the General command? Practically the will of his chief is the code of the Jesuit. We shall first consider the powers of the General. The original bull of Paul III. constituting the Company gave to “Ignatius de Loyola, with nine priests, his companions,” the power to make Constitutions and particular rules, and also to alter them. The legislative power thus rested in the hands of the General and his company — that is, in a “Congregation” representing them. But when Loyola died, and Lainez succeeded him as General, one of his first acts was to assemble a Congregation, and cause it to be decided that the General only had the right to make rules.4 This crowned the autocracy of the General, for while he has the power of legislating for all others, no one may legislate for him. He acts without control, without responsibility, without law. It is true that in certain cases the society may depose the General. But it cannot exercise its powers unless it be assembled, and the General alone can assemble the Congregation. The whole order, with all its authority, is, in fact, comprised in him. In virtue of his prerogative the General can command and regulate everything in the society. He may make special Constitutions for the advantage of the society, and he may alter them, abrogate them, and make new ones, dating them at any time he pleases. These new rules must be regarded as confirmed by apostolic authority, not merely from the time they were made, but the time they are dated. The General assigns to all provincials, superiors, and members of the society, of whatever grade, the powers they are to exercise, the places where they are to labor, the missions they are to discharge, and he may annul or confirm their acts at his pleasure. He has the right to nominate provincials and rectors, to admit or exclude members, to say what proffered dignity they are or are not to accept, to change the destination of legacies, and, though to give money to his relatives exposes him to deposition, “he may yet give alms to any amount that he may deem conducive to the glory of God.” He is invested moreover with the entire government and regulation of the colleges of the society. He may institute missions in all parts of the world. When commanding in the name of Jesus Christ, and in virtue of obedience, he commands under the penalty of mortal and venial sin. From his orders there is no appeal to the Pope. He can release from vows; he can examine into the consciences of the members; but it is useless to particularize — the General is the society.5 The General alone, we have said, has power to make laws, ordinances, and declarations. This power is theoretically bounded, though practically absolute. It has been declared that everything essential (“Substantia Institutionis”) to the society is immutable, and therefore removed beyond the power of the General. But it has never yet been determined what things belong to the essence of the institute. Many attempts have been made to solve this question, but no solution that is comprehensible has ever been arrived at; and so long as this question remains without an answer, the powers of the General will remain without a limit. Let us next attend to the organization of the society. The Jesuit monarchy covers the globe. At its head, as we have said, is a sovereign, who rules over all, but is himself ruled over by no one. First come six grand divisions termed Assistanzen, satrapies or princedoms. These comprehend the space stretching from the Indus to the Mediterranean; more particularly India, Spain and Portugal, Germany and France, Italy and Sicily, Poland and Lithuania.6 Outside this area the Jesuits have established missions. The heads of these six divisions act as coadjutors to their General; they are staff or cabinet. These six great divisions are subdivided into thirty-seven Provinces.7 Over each province is placed a chief, termed a Provincial. The provinces are again subdivided into a variety of houses or establishments. First come the houses of the Professed, presided over by their Provost. Next come the colleges, or houses of the novices and scholars, presided over by their Rector or Superior. Where these cannot be established, “residences” are erected, for the accommodation of the priests who perambulate the district, preaching and hearing confessions. And lastly may be mentioned “mission-houses,” in which Jesuits live unnoticed as secular clergy, but seeking, by all possible means, to promote the interests of the society.8 From his chamber in Rome the eye of the General surveys the world of Jesuitism to its farthest bounds; there is nothing done in it which he does not see; there is nothing spoken in it which he does not hear. It becomes us to note the means by which this almost superhuman intelligence is acquired. Every year a list of the houses and members of the society, with the name, talents, virtues, and failings of each, is laid before the General. In addition to the annual report, every one of the thirty-seven provincials must send him a report monthly of the state of his province, he must inform him minutely of its political and ecclesiastical condition. Every superior of a college must report once every three months. The heads of houses of residence, and houses of novitiates, must do the same. In short, from every quarter of his vast dominions come a monthly and a tri-monthly report. If the matter reported on has reference to persons outside the society, the Constitutions direct that the provincials and superiors shall write to the General in cipher. “Such precautions are taken against enemies,” says M. de Chalotais. “Is the system of the Jesuits inimical to all governments?” Thus to the General of the Jesuits the world lies “naked and open.” He sees by a thousand eyes, he hears by a thousand ears; and when he has a behest to execute, he can select the fittest agent from an innumerable host, all of whom are ready to do his bidding. The past history, the good and evil qualities of every member of the society, his talents, his dispositions, his inclinations, his tastes, his secret thoughts, have all been strictly examined, minutely chronicled, and laid before the eye of the General. It is the same as if he were present in person, and had seen and conversed with each. All ranks, from the nobleman to the day-laborer; all trades, from the opulent banker to the shoemaker and porter; all professions, from the stoled dignitary and the learned professor to the cowled mendicant; all grades of literary men, from the philosopher, the mathematician, and the historian, to the schoolmaster and the reporter on the provincial newspaper, are enrolled in the society. Marshalled, and in continual attendance, before their chief, stand this host, so large in numbers, and so various in gifts. At his word they go, and at his word they come, speeding over seas and mountains, across frozen steppes, or burning plains, on his errand. Pestilence, or battle, or death may lie on his path, the Jesuit’s obedience is not less prompt. Selecting one, the General sends him to the royal cabinet. Making choice of another, he opens to him the door of Parliament. A third he enrolls in a political club; a fourth he places in the pulpit of a church, whose creed he professes that he may betray it; a fifth he commands to mingle in the saloons of the literati; a sixth he sends to act his part in the Evangelical Conference; a seventh he seats beside the domestic hearth; and an eighth he sends afar off to barbarous tribes, where, speaking a strange tongue, and wearing a rough garment, he executes, amidst hardships and perils, the will of his superior. There is no disguise which the Jesuit will not wear, no art he will not employ, no motive he will not feign, no creed he will not profess, provided only he can acquit himself a true soldier in the Jesuit army, and accomplish the work on which he has been sent forth. “We have men,” exclaimed a General exultingly, as he glanced over the long roll of philosophers, orators, statesmen, and scholars who stood before him, ready to serve.

Moral Code of the Jesuits. The Jesuit cut off from Country — from Family — from Property — from the Pope even — The End Sanctifies the Means — The First Great Commandment and Jesuit Morality — When may a Man Love God? — Second Great Commandment — Doctrine of Probabilism — The Jesuit Casuists — Pascal — The Direction of the Intention — Illustrative Cases furnished by Jesuit Doctors — Marvellous Virtue of the Doctrine — A Pious Assassination.

WE have not yet surveyed the full and perfect equipment of those troops which Loyola sent forth to prosecute the “heretics.” Nothing was left untaught of and unprovided for which might assist them in covering their opponents with defeat, and crowning themselves with victory. They were set free from every obligation, whether imposed by the natural or the Divine law. Every stratagem, artifice, and disguise were lawful to men in whose favor all distinction between right and wrong had been abolished. They might assume as many shapes as Proteus, and exhibit as many colors as the chameleon. They stood apart and alone among the human race. First of all, they were cut off from country. Their vow bound them to go to whatever land their General might send them, and to remain there as long as he might appoint. Their country was the society. They were cut off from family and friends. Their vow taught them to forget their father's house, and to esteem themselves holy only when every affection and desire which nature had planted in their breasts had been plucked up by the roots. They were cut off from property and wealth. For although the society was immensely rich, its individual members possessed nothing. Nor could they cherish the hope of ever becoming personally wealthy, seeing they had taken a vow of perpetual poverty. If it chanced that a rich relative died, and left them as heirs, the General relieved them of their vow, and sent them back into the world, for so long a time as might enable them to take possession of the wealth of which they had been named the heirs; but this done, they returned laden with their booty, and, resuming their vow as Jesuits, laid every penny of their newly-acquired riches at the feet of the General. They were cut off, moreover, from the State. They were discharged from all civil and national relationships and duties. They were under a higher code than the national one — the Institutions namely, which Loyola had edited, and the Spirit of God had inspired; and they were the subjects of a higher monarch than the sovereign of the nation — their own General. Nay, more, the Jesuits were cut off even from the Pope. For if their General “held the place of the Omnipotent God,” much more did he hold the place of “his Vicar.” And so was it in fact; for soon the members of the Society of Jesus came to recognize no laws but their own, and though at their first formation they professed to have no end but the defense and glory of the Papal See, it came to pass when they grew to be strong that, instead of serving the tiara, they compelled the tiara to serve the society, and made their own wealth, power, and dominion the one grand object of their existence. They were a Papacy within the Papacy — a Papacy whose organization was more perfect, whose instincts were more cruel, whose workings were more mysterious, and whose dominion was more destructive than that of the old Papacy. So stood the Society of Jesus. A deep and wide gulf separated it from all other communities and interests. Set free from the love of family, from the ties of kindred, from the claims of country, and from the rule of law, careless of the happiness they might destroy, and the misery and pain and woe they might inflict, the members were at liberty, without control or challenge, to pursue their terrible end, which was the dethronement of other power, the extinction of other interest but their own, and the reduction of humans into slaves. The key-note of their ethical code is the famous maxim that the end sanctifies the means. Before that maxim the eternal distinction of right and wrong vanishes. Not only do the stringency and sanctions of human law dissolve and disappear, but the authority and majesty of the Decalogue are overthrown. There are no conceivable crime, villainy, and atrocity which this maxim will not justify. Nay, such become dutiful and holy, provided they be done for “the greater glory of God,” by which the Jesuit means the honor, interest, and advancement of His society. In short, the Jesuit may do whatever he has a mind to do, all human and Divine laws notwithstanding. This is a very grave charge, but the evidence of its truth is, unhappily, too abundant, and the difficulty lies in making a selection. The Jesuit doctors using their casuistry have done a lot to make sin look as no si. “The first and great commandment in the law,” said the same Divine Person who proclaimed it from Sinai, “is to love the Lord thy God.” The Jesuit casuists have set men free from the obligation to love God. Escobar[1] collects the different sentiments of the famous divines of the Society of Jesus upon the question, When is a man obliged to have actually an affection for God? The following are some of these: — Suarez says, “It is sufficient a man love him before he dies, not assigning any particular time. Vasquez, that it is sufficient even at the point of death. Others, when a man receives his baptism: others, when he is obliged to be contrite: others, upon holidays. But our Father Castro-Palao[2] disputes all these opinions, and that justly. Hurtado de Mendoza pretends that a man is obliged to do it once every year. Our Father Coninck believes a man to be obliged once in three or four years. Henriquez, once in five years. But Filiutius affirms it to be probable that in rigor a man is not obliged every five years. When then? He leaves the point to the wise.” “We are not,” says Father Sirmond, “so much commanded to love him as not to hate him,”[3] Thus do the Jesuit theologians make void “the first; and great commandment in the law.” The second commandment in the law is, “Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself.” This second great commandment meets with no more respect at the hands of the Jesuits than the first. Their morality dashes both tables of the law in pieces; charity to man it makes void equally with the love of God. The methods by which this may be done are innumerable.[4] The first of these is termed probabilism. This is a device which enables a man to commit any act, be it ever so manifest a breach of the moral and Divine law, without the least restraint of conscience, remorse of mind, or guilt before God. What is probabilism? By way of answer we shall suppose that a man has a great mind to do a certain act, of the lawfulness of which he is in doubt. He finds that there are two opinions upon the point: the one probably true, to the effect that the act is lawful; the other more probably true, to the effect that the act is sinful. Under the Jesuit regimen the man is at liberty to act upon the probable opinion. The act is probably wrong, nevertheless he is safe in doing it, in virtue of the doctrine of probabalism. It is important to ask, what makes all opinion probable? To make an opinion probable a Jesuit finds easy indeed. If a single doctor has pronounced in its favor, though a score of doctors may have condemned it, or if the man can imagine in his own mind something like a tolerable reason for doing the act, the opinion that it is lawful becomes probable. It will be hard to name an act for which a Jesuit authority may not be produced, and harder still to find a man whose invention is so poor as not to furnish him with what he deems a good reason for doing what he is inclined to, and therefore it may be pronounced impossible to instance a deed, however manifestly opposed to the light of nature and the law of God, which may not be committed under the shield of the monstrous dogma of probabilism.[5] We are neither indulging in satire nor incurring the charge of false-witness-bearing in this picture of Jesuit theology. “A person may do what he considers allowable,” says Emmanuel Sa, of the Society of Jesus, “according to a probable opinion, although the contrary may be the more probable one. The opinion of a single grave doctor is all that is requisite.” A yet greater doctor, Filiutius, of Rome, confirms him in this. “It is allowable,” says he, “to follow the less probable opinion, even though it be the less safe one. That is the common judgment of modern authors.” “Of two contrary opinions,” says Paul Laymann, “touching the legality or illegality of any human action, every one may follow in practice or in action that which he should prefer, although it may appear to the agent himself less probable in theory.” he adds: “A learned person may give contrary advice to different persons according to contrary probable opinions, whilst he still preserves discretion and prudence.” We may say with Pascal, “These Jesuit casuists give us elbow-room at all events!”[6] It is and it is not is the motto of this theology. It is the true Lesbian rule which shapes itself according to that which we wish to measure by it. Would we have any action to be sinful, the Jesuit moralist turns this side of the code to us; would we have it to be lawful, he turns the other side. Right and wrong are put thus in our own power; we can make the same action a sin or a duty as we please, or as we deem it expedient. To steal the property, slander the character, violate the chastity, or spill the blood of a fellow-creature, is most probably wrong, but let us imagine some good to be got by it, and it is probably right. The Jesuit workers, for the sake of those who are dull of understanding and slow to apprehend the freedom they bring them, have gone into particulars and compiled lists of actions, esteemed sinful, unnatural, and abominable by the moral sense of all nations hitherto, but which, in virtue of this new morality, are no longer so, and they have explained how these actions may be safely done, with a minuteness of detail and a luxuriance of illustration, in which it were tedious in some cases, immodest in others, to follow them. One would think that this was license enough. What more can the Jesuit need, or what more can he possibly have, seeing by a little effort, of invention he can overleap every human and Divine barrier, and commit the most horrible crimes, on the mightiest possible scale, and neither feel remorse of conscience nor fear of punishment? But this unbounded liberty of wickedness did not content the sons of Loyola. They panted for a liberty, if possible, yet more boundless; they wished to be released from the easy condition of imagining some good end for the wickedness they wished to perpetrate, and to be free to sin without the trouble of assigning even to themselves any end at all. This they have accomplished by the method of directing the intention. This is a new ethical science, unknown to those ages which were not privileged to bask in the illuminating rays of the Society of Jesus, and it is as simple as convenient. It is the soul, they argue, that does the act, so far as it is moral or immoral. As regards the body's share in it, neither virtue nor vice can be predicated of it. If, therefore, while the hand is shedding blood, or the tongue is calumniating character, or uttering a falsehood, the soul can so abstract itself from what the body is doing as to occupy itself the while with some holy theme, or fix its meditation upon some benefit or advantage likely to arise from the deed, which it knows, or at least suspects, the body is at that moment engaged in doing, the soul contracts neither guilt nor stain, and the man runs no risk of ever being called to account for the murder, or theft, or calumny, by God, or of incurring his displeasure on that ground. We are not satirizing; we are simply stating the morality of the Jesuits. “We never,” says the Father Jesuit in Pascal's Letters, “suffer such a thing as the formal intention to sin with the sole design of sinning; and if any person whatever should persist in having no other end but evil in the evil that he does, we break with him at once — such conduct is diabolical. This holds true, without exception, of age, sex, or rank. But when the person is not of such a wretched disposition as this, we try to put in practice our method of directing the intention, which simply consists in his proposing to himself, as the end of his actions, some allowable object. Not that we do not endeavor, as far as we can, to dissuade men from doing things forbidden; but when we cannot prevent the action, we at least, purify the motive, and thus correct the viciousness of the means by the goodness of the end. Such is the way in which our Fathers [of the society] have contrived to permit those acts of violence to which men usually resort in vindication of their honor. They have no more to do than to turn off the intention from the desire of vengeance, which is criminal, and to direct it to a desire to defend their honor, which, according to us, is quite warrantable. And in this way our doctors discharge all their duty towards God and towards man. By permitting the action they gratify the world; and by purifying the intention they give satisfaction to the Gospel. This is a secret, sir, which was entirely unknown to the ancients; the world is indebted for the discovery entirely to our doctors. You understand it now, I hope.[7]

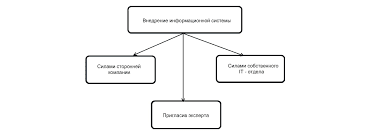

Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|