|

|

Reform Movements in Germany. Lutheranism.T he general dissatisfaction with the Roman Church and endeavors toward its reformation in the 14th and 15th centuries, was decided in the 16th century by the so-called reformation. It began in Germany with the emergence of Martin Luther — an Augustinian friar — who was the founder of a new religious order in the West. Luther descended from poor parents that were peasants. He was born in 1483 and received his education in Erfurt university. Being a zealous Catholic and religiously disposed, he entered an Augustinian Erfurt monastery in 1505, where he led an ascetic life. He began to study the teachings of the Scripture, works of Augustine and the middle-age mystics. He became a priest in 1507, while in 1508 he relocated to Wittenberg where he took up a post as a professor at the university. In 1510 Luther undertook a trip to Rome on matters relating to the order. The dissolute life of the papal court of Leo X, disbelief and blasphemy among the clergy, all brought about an upheaval in his convictions. Imbued with the knowledge of his own sinfulness, he strived to attain absolution from God with the help of the Church and its means (deeds of self-denial). Now, he began to think that the Church and the hierarchy that he witnessed in Rome, were incapable of giving this to people. Under the influence of Augustine’s writings and the mystics, he became convinced that only a personal contact with and faith in the Redeemer may justify a human being. In 1517, requiring finances to sustain his extravagant lifestyle, Pope Leo X resorted to selling indulgences. A Dominican monk Tezel — an agent of the archbishop of Mainz — appeared in Wittenberg and began to sell indulgences in a shop, just like a market trader. Outraged by this sacrilege of the release of sins, he compiled 95 theses against indulgences, and on deeds that are above those that are required, as well as on purgatory. According to tradition of those times, he presented his theses in the church of a Wittenberg castle, and challenged Tezel to a debate. Tezel and his supporters accepted the challenge. Luther’s theses and the controversy attracted a universal interest in other cities in Germany. Luther received much support and the Saxon koorfurst Frederick the Wise. Initially the Pope regarded the encounter between Luther and the Dominicans as an ordinary argument, albeit unpleasant to him, among monastic orders, and only wished for it to cease. In 1518, he summoned Luther to Rome. When koorfurst and the university demanded this be resolved immediately, the Pope referred the matter for resolution to cardinal Gaetano. Arriving at Augsburg, the cardinal took the side of Luther’s opponent and superciliously demanded renouncement of his ideas. Luther refused. Another authorized agent from the Pope acted in a different manner. He punished Tezelthereby letting Luther know that he was on his side. Furthermore, he convinced him to write a letter to the Pope, indicating his obedience, to which Luther complied, promising not to raise any arguments if his opponents did likewise. Meanwhile, in 1519, a professor Johann Eck of Ingolstadt university entered into a dispute with one of Luther’s students, and eventually with Luther himself. The dispute now widened to include the question of the Pope’s primacy. The adversaries remained with their own convictions although in Germany, the empathy for Luther strengthened. Another Wittenberg professor — Philip Melanchthon — joined him. He was an authority on the Jewish and Greek languages, and participated actively in the reformation. All the free-thinking people in Germany (humanists) were also on Luther’s side, who became bolder after the dispute and decidedly went down the path of reformation, not having any dealings with papacy. In 1520, he published an appeal to “the Imperial Highness and Christian knighthood of the German nation,” in which he invited everyone to reject the papal yoke. The appeal spread throughout the whole of Germany and created a strong impression. The Latin theologians informed Pope Leo X that the dispute aroused by Luther, was posing a serious danger to the Church. This forced the Pope to act more harshly. In 1520, he issued a bull, which subjected Luther — as a heretic — to excommunication, and all his works to the flames. This bull did not realize the expected reaction. Luther’s works were burned in a few towns only. Luther responded to the general Council with an “appellation” and a treatise “against antichrist’s bull.” The actual bull itself was publicly burned by Luther. In 1520, the Pope damned him as an unrepentant heretic, and requested the German Emperor, Carl V (1519-56) to banish him. Although Carl favored this, because of the wishes of the Germany’s knights, he decided to examine the matter at the imperial diet in Worms (1521). Present at this assembly were a number of Pope’s legates as well as many supporters of reform. Occupying a prominent position among them was the elector Frederick the Wise of Saxony. At the insistence of Luther’s supporters, he was invited to the diet for his explanation, even though the legates protested against this, pointing out that he was excommunicated from the Church. At one of the sittings, Luther was shown his works and suggested that he renounce them. However, he was resolute and in his own defense stated that the only time he will do this is if his teachings are refuted on the basis of the Gospel and clear deductions. Consequently, the diet released Luther without making any decision against him. It was only at the end of the sitting — when many of adherents of reform had left — and for political reasons in maintaining good relations with the Pope, that the emperor passed a decree, which denied Luther and his followers protection of the law and were condemned to banishment. Anticipating this to happen, the Saxon elector had earlier organized to hide Luther in a remote castle at Wartburg. Moreover, nobody in Germany worried about fulfilling the Worms edict. In Wartburg, Luther spent most of his time in translating the Bible into German. At the same time, while Luther was in isolation, the reform movement in Wittenberg — with Melanchthon’s participation — continued. A complete rift with the Roman Church eventuated — private church services were abolished, priests entered into marriage, monks were abandoning their monasteries etc. Some of the Luther’s more zealous followers, reached such a stage where they forcibly stopped church services, threw out icons from churches etc. So-called prophets from Zwickau appeared in the city of Zwickau who subsequently crossed over into Wittenberg. In the name of direct revelations, they preached the overthrow of all church and civil order. As soon as he became are of this, Luther hurried to Wittenberg and through his sermons, succeeded in subduing the unrest — at least in that city. In other parts of Germany, religious turmoil still persisted and assumed a political character, having evoked a big movement — the peasants’ war. The German emperor was engaged in a war against the French, while the nobles, themselves disgruntled with the Roman Church, were sympathetic to the new church directions. The papal legates lost all authority in Germany and were ignored by everyone. Luther and Melanchthon continued unimpeded to spread the new viewpoint, explaining the basis of the teachings and strengthening the reform movement. In 1521, Melanchthon published his work, in which he simply and clearly outlined the new religious doctrine. In 1522, Luther published his translation of the New Testament for general use. This new doctrine contained many thoughts that were reminiscent of the reformation’s predecessors, especially Wycliffe’s, and formed a complete antithesis to Catholicism. In rejecting the deviation and abuses of Catholicism, he also rejected all its truths. By taking the basic position that a person is justified through faith alone in the Redeemer (which is a gift from God) and a personal communion with Him, Luther rejected all the means concerning salvation — Church, hierarchy and Mysteries. According to Luther’s teachings, the Church is not the treasury of gifts of grace but a society of similar believers in Christ. Hierarchical services are superfluous as everyone carries out his own salvation. “Priesthood” belonged to everyone. Therefore, he replaced the hierarchy with ordinary officials — teachers, preachers, their supervisors, as well giving higher duties to individuals with civil authority. Luther looked upon Mysteries as pious customs. He permitted Holy Communion, believing in the presence of Christ, although not explaining His presence. He rejected the act of transubstantiation. He also rejected the heavenly intercessors, the veneration of saints, their relics and bowing to icons, as well as the holy Tradition. Recognizing the Holy Gospel only, he presented his interpretation and understanding of it to every faithful. Luther established a new religious society, which received the name Lutheranism.

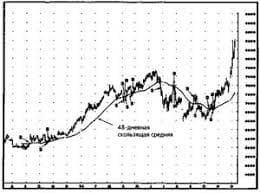

Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|