|

|

Religious Directions in the Roman Church.T he following text outlines the struggle of papacy with internal enemies. These enemies were jansenism and quietism — spiritual directions that arose within the Roman Church itself and then troubled her for a considerable time. Jansenism appeared in the 17th century as a protest against the moral system of the Jesuits, which undermined all moral fundamentals but nonetheless tolerated — and even sanctioned — by the Church. By laying great emphasis on the free will of a person in matters of salvation, the Jesuits regarded sin as conscious and unforced departure from God’s commandments. However, from this they made a casuistic conclusion that if for example, habit, passion and others attract a person toward sin, then sin should not be attributed to him as he committed it apart from his free will. It was on this basis that they released people from all types of sins and crimes at confessionals. These immoral teachings came under attack from a renowned Dutch theologian, Cornelis Jansen. He was born in 1585 and died in 1638. In 1630, he became professor of theology at Louvain university, where he lectured along strict Augustinian spirit. During this time, he had several controversial arguments with the Jesuits. In 1636, he became bishop of Ypres. Here he completed his work “Augustinus.” He wrote somewhat lesser works in which he maintained polemics against the Jesuits. In 1635, he issued a pamphlet in which he condemned cardinal Richelieu for his support of the Protestants during the Thirty Year war. Contrary to the jesuits, Jansen taught that a person’s will wasn’t free as it had been enslaved by passions and a drive toward the earthly. As a consequence, a human being is constantly subject to sin; what liberates a person from sin is not the Jesuit all-justifying and excusable confession, but grace, which cleanses the soul of its passions, awakens repentance and love toward God, and consolidates the will in goodness. According to Jansen’s teachings, it is under the effect of this grace that an essentiality arises to lead a strictly righteous life, withdrawing fully from the world with its temptations. Jansen’s work — published after his death — attracted widespread attention. In France, where there were pronounced dissatisfaction with the jesuits, it was greeted with approval. Here, supporters of Augustus and Jansen and opponents of the jesuits formed a group; its spiritual center was the women’s monastery near Paris — Port-Royal-des-Champs. The Abbe of monastery St. Cyran, Jean Duvergier de Hauranne established a Jansen community within it. The group slowly grew as many clergy, erudite, individuals from well-known families and others joined it. Many of those who joined came from the Arnaud family. Among other members, the most famous was Blaise Pascal, philosopher, physicist and mathematician. Members of the group, Jansenites, observed monastic life without any vows, dedicating themselves to prayer and labor, physical as well as (more so) writing. At the Port Royal monastery, a theological college was established, becoming a nursery for Jansenism. Its viewpoint quickly spread throughout the whole of France, and beyond its boundaries, where it was accepted always sympathetically. After the publication of Jansen’s book in 1840, the jesuits realized the able to teachings it contained posed a great danger for their operations. Consequently, in 1843, they were able to procure its condemnation by Pope Urban VIII (1623-44). However, jansenism was not destroyed — the jansenites in France and the Netherlands, declared their objection against papal ruling, and entered into literary polemics with the jesuits. Then the jesuits outlined 5 instances out of the book and presented them to Pope Innocent X (1644-55) as being heretical. In 1653, the Pope condemned them in a special bull and sent it to France. However, the Jansenites and many French bishops lodged strong protests against the bull. They argued that the condemned instances did not exist in Jansen’s book, and when Pope Alexander VII declared — without right of appeal — that such instances really do exist in the book, they began to protest that the Pope was abusing his position of infallibility by confirming non-existent facts. The dispute continued up to 1668, when Pope Clement IX expressed his agreement to the bishops — holding to Jansen’s teachings — signing a general condemnation of those 5 instances, without mentioning that they form part of Jansen’s teachings. However, the Jesuits were not happy with this settlement, particularly as the jansenites — in their polemic writings — kept revealing with fine detail their immoral teachings, their dissolute lifestyle and all their intrigues. Consequently, they continued to alienate the Popes, as well as the French king Louis XIV. In the beginning of the 18th century, the jesuits finally achieved the persecution of the jansenites. By Louis’ decree in 1709, Port-Royal and its college were closed, while in 1713, Pope Clement XI issued a bull — Unigenitus — which anathematized all the teachings of the jansenites, formulated in 101 circumstances. Because the papal condemnation in its material essence was the condemnation of the highly respected Church educator, Blessed Augustine, the bull created great concern in France. There followed from the many people (headed by the archbishop of Paris) that held Augustine and Jansen in high esteem, an open protest against the papal bull, which didn’t help much. Because of the Jesuit’s intrigues, the government began to persecute and expel the Jansenites. As a result, many of them fled to the Netherlands. Interference by secular authorities in Church affairs, resulted in Jansenism ceasing to be a purely religious issue and assuming a distinctly social tone. Parliament refused to register Clement’s XI new bull. What damaged Jansen was that some of his more illustrious adherents, began to fabricate miracles and maintain superstitions. Later, political opposition parties lost interest in Jansenism, resorting to other means in their struggle against the government. On the other hand, the Catholic kings themselves began a battle with the Jesuits. From the mid-eighteenth century, Jansenism disappeared in France. In the Netherlands, jansenism evolved into an independent church. The Reformation movement eliminated most of the bishops; the head of the local Catholics was an archbishop, the so-called apostolic vicar in Utrecht. Due to the archbishop coming out in favor of Jansenism in 1702, Utrecht became its center. Although Clement XI removed the archbishop, the local chapter refused to recognize any of the candidates that he sent to replace him. For more than 20 years, Utrecht remained without an archbishop. In order to put an end to this, the local chapter chose its own candidate; the Pope refused to confirm him, and the local chapter carried on without it. In 1724, the archbishop was confirmed by the Babylonian bishop, in place of the Pope. This uncommon Utrecht church came into being from that point on. Today, the archbishop is chosen by the bishops of Harlem and Deventer. In acknowledging the Pope’s primacy — who nonetheless refuses to confirm any newly appointed archbishops — the Church regards itself as Catholic, even to the point of condemning jansenism. However, it stubbornly refuses to accept the “Unigenitus” bull. In 1872, the Utrecht Church united with that of the old-catholic one. The other religious movement that emerged in the 17th century was called quietism (from the Latin word “quiet”), and was of less significance to the papacy than Jansenism. However it deserves attention as a protest against the lifeless theological formalism and ritual exterior, upon which the religious life of the Roman Church was based. Quietism had its beginnings from the Spanish priest Miguel de Molinos, who maintained mystical ideas and a pious life. In his sermons and especial work “Spiritual Guide,” he developed the following teaching: the highest Christian perfection lies in the sweet divine peace, uninterrupted by any earthly cares. This peace is attained through inner prayer and direct vision of God. The soul, immersed in this vision, submits itself to Him totally — begins to love Him with pure love i.e. devoid of all mercenary thoughts, not thinking of any rewards or punishment. Yielding itself in this manner to God, it loses even its own identity and as though consumed by Divinity, it has no will of its own but is directed by God’s will. Such a state of the soul is that sweet divine peace toward which every Christian should aspire. Everything earthly and outward, which according to these teachings include church establishments and churches, church services etc. become superfluous. Initially, Molinos attracted many people in Spain, then in Rome — where from 1669 he was a priest. However the Jesuits soon put an end to his activities. Presented to an inquisitorial court in 1687, he was condemned as a heretic and imprisoned, where he died in 1696. Notwithstanding such a sad ending of the first preacher of Quietism, it still continued to spread in Spain, Italy and especially in France. Women in particular indulged in mystical religious contemplation's and meditations. During Louis XIV reign in France, the most ardent followers of Quietism were Madame Guyon and Lacombe. Their sermons on divine selfless love, pointlessness of churches and church services etc. preached throughout France and Switzerland, earned them many followers. Even the well-known French bishop Fenelon, adhered to Quietismatic ideas. The strong spread of quietism prompted the French bishops — with the renowned Bossuet as their head — to take measures against him. In 1695, under the kings directive, they assembled a council, which condemned the teachings of Quietism as being heresy and found its main representative — Madame Guyon — guilty and imprisoned. However, even after this, the controversy continued with Fenelon emerging as its defender and engaging in polemics with Bossuet. It was only at the request of the king that in 1699, Pope Innocent XII concluded the dispute with Fenelon, who accepted this action unequivocally. Although in the following period Quietism faded of its own accord, the mystical directions of the Roman Church, always had a small number of adherents. Jansenism and quietism inserted a rift in the Roman Church. In opposition to them, in the beginning of the 18th century, among the extreme adherents of papal Catholicism, an especially strong development began of the previously existing strong Catholic directive — ultra-montanism. These were supporters who thought the Pope should have authority not only within the church sphere, but should have a higher power than that of kings and governments, and that he shouldn’t allow any independence to churches in various countries, even in questions of internal structure. The name ultra-montanism, which came from the Latin “ultra montes” (beyond the mountains i.e. the Alps), was applied in the middle ages to the Pope and his supporters in France and Germany — initially at the Constance Council. Ultra-montanism contained ideas of absolute authority of the Popes, which were developed a long time ago by Gregory VII, Innocent III and Boniface VIII. After the council of French clergy in 1682 gave the impetus for the development of gallicanism, the opposing direction of the Pope and the Italian clergy was given the name ultra-montanism in France, which came into general use from that time on. Whereas before the beginning of the 18th century, ultra-montanism was nearly the sole attribute of the papal throne and the Roman curia, now it begins to spread among the clergy and society. This was aided mainly by the Jesuits who had become great defenders of ultra-montanism views — after Pope Clement XI came out openly in their favor and condemned Jansenism in 1713. It is true that in the second half of the 18th century, after the abolition of the Order of Jesuits, ultra-montanism vanished. However, after the affirmation of the papacy in 1815, it once again became a significant force. Currently, ultra-montanism exists in all Catholic countries. The principles that they promote in literature and in life are: papal authority is the sole divine authority on earth; it is not constrained — in the broadest sense — both in spiritual and secular matters of Christians; all Christians on earth must submit unconditionally to this authority, believe the way they are directed and be part of the one Roman-Catholic Church; it’s the only Church that embodies true Christianity; the Pope is its sole guardian and infallible expounder; all those that are not within the Catholic Church or oppose it and its head, the Pope, cannot even hope for salvation. In practice, the ultra-montanists are noted for their impatience toward not only other religious beliefs, but also to all other opinions that don’t agree with theirs. Their views on the world are outlined especially vividly in the work “Du pape” by the French author, Joseph de Mestra (1754-1821), an activist in the Piedemont government. Presently, the ultra-montanists regard all clerics as their enemies.

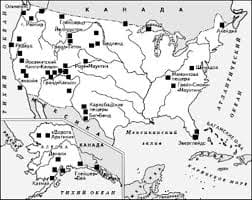

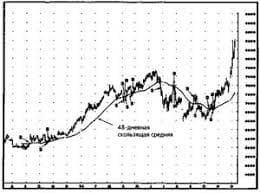

Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  Живите по правилу: МАЛО ЛИ ЧТО НА СВЕТЕ СУЩЕСТВУЕТ? Я неслучайно подчеркиваю, что место в голове ограничено, а информации вокруг много, и что ваше право...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|