|

|

General Dissatisfaction with the Roman Church.T he appearance of sectarian societies in the West, reflected the strong protest against the depravity of the Roman church. However, between the 11th and 15th centuries, the sectarians were not the only ones to arise against the deficiencies that ruled the church. There were many dissatisfied individuals of all levels in the Christian society in the West with the then prevailing situation. However, they didn’t separate themselves from the church but only demanded reformation. When abuse by the papacy and clergy reached its limits, the demands for reform became more insistent. Papacy especially became hated, having converted the church into a human kingdom. In the 14-15 centuries — Emperors with their governments, and intellectuals, bishops, clergy and the people — demanded in the name of the Gospel and Apostolic Christianity, that there be a church reform in the leadership and its members. They demanded from the Pope, that he abandon his secular power and confine himself to spiritual authority only — to be used without force and with discretion within the confines of church laws. The introduction of strict discipline among the hierarchy and clergy, and improvement in their morals was also demanded. There were calls for the elimination of indulgences as well as cleansing the teachings of their scholastic excrescence's. There were also demands for the spread of religious education among the people and the restoration of piety within the church etc.. Such reforms were thoroughly enunciated in the writings of educated theologians, proving their essentiality. The center of the reform movement was located in a Paris university. It was from this university that the champions of reform emerged — Chancellor of the university, John Jerson (died 1429), university rector Nicholas von Clemange (died 1440) and others. Naturally, the Popes didn’t want to know about any reforms. This prompted governments and even some private individuals, to undertake their own efforts. The government aimed to achieve this through reformatory councils of — Pisa, Constance and Basle. Private figures, like John Wycliffe in England, John Huss in Bohemia and Savonarola in Italy, all relied on the assistance of the intellectuals and the masses. However, endeavors remained just that — endeavors. The western Christian society was still under the influence of papal might, and was afraid to make the decisive step. On the other hand, centuries-old papal experience gave them an opportune chance to destroy the plans for reformation. Nevertheless, all these endeavors paved the way toward real reformation.

Wycliffe. The English theologian, John Wycliffe (1324-84) emerged with his reformatory ideas in the latter half of the 14th century. The situation was favorable to him. During the reign of Edward the III, the English government had begun to gradually free itself from papal tutelage, and therefore looked favorably upon its opponents. Wycliffe began in 1356 with the publication of his work “about the last days of the Church.” Then during the confrontation of (1360), between Oxford university and impoverished monks, he began to orally and in writing argue that monasticism was insolvent. When the government refused to pay the papal tribute, Wycliffe came out in defense of the government. This earned him a professorship and doctorate at Oxford university. In 1374, commissioned by the government and in the company of others traveled, he traveled to Avignon for talks with the Pope. Here, he came face to face with the corruptness of the papacy and upon his return, began to preach that the Pope is an “antichrist.” In his attacks, Wycliffe began to reject the priesthood, arguing that it’s not the consecration that is the basis of their right to control and celebrate Divine Services, but the piety of individuals. This gave the impoverished monks the opportunity to accuse him of heresy. In 1378, a court was convened by Pope Gregory the XI to judge Wycliffe. Due to the protection of the English government, he was found guiltless, having satisfied the court with his explanations. This coincided with the papal split. Wycliffe renewed his attacks and began to completely reject the bishopric authority. He proposed to re-establish the “apostolic Presbyterian order.” He fully rejected Holy Tradition, teachings on purgatory and indulgences. He recognized the Gospel as the only norm of religious doctrine. He regarded Chrismation as not essential, oral confession as a violation of conscience, proposing that an inner penitence before God is sufficient. In the Mystery of the Eucharist, he recognized Christ’s spiritual and not His actual presence. He argued about the necessity of having full simplicity in Divine Services, proposed the allowance of priests to marry, and abolish the monastic order, or at least regard the monks on the same level as laymen. In general, Wycliffe strove to limit all means of contact between God and man, and regarded salvation as being dependent upon the personal relationship between man and the Redeemer. He founded an order of pious men for the dissemination of religious teachings and Evangelical sermons to the people. He began to translate the Gospel into English. Once again persecutions re-commenced against him. In 1382, a council in London condemned 24 areas of his teachings as heretical. King Richard the II could protect only Wycliffe himself, who retired from Oxford to his parish at Lutterworth, where he later died. Shortly before his death, Wycliffe wrote a treatise in which he outlined his thoughts on reform. As a result, he was condemned at the councils of Rome (1412) and Constance (1415). He left followers not only from the ordinary people, but from the highest class of society. They were called heretical Lollards. Under papal pressure, the English government refused them sympathy, and even assisted the church in their persecutions against them and they soon lost their significance. However, Wycliffe’s ideas sent out deep roots in England, as in many other countries.

John Huss. John Huss was a professor of theology in a Prague university in Bohemia. While Wycliffe reached a point of rejecting a great deal that was significant in religion, Huss on the other hand, in revolting against the evil practices of the Roman church, remained firm on the basics of the church, and even more — he was a defender of the early Orthodoxy. He was born in 1369, in Husinec that was located in Southern Bohemia; he received his education in a Prague university, where from 1398 he taught theology. There was talk of regeneration of the church even in Bohemia. It was there in the 14th century that a desire arose for the restoration of early Orthodoxy, which was preached in that region by Saints Cyril and Methodius. Divine Services in Slavonic language and the partaking of Holy Sacraments under both guises, formed the foremost desire of the Bohemians. In occupying the professorial chair, John Huss became a passionate champion for church reform, in the sense of returning to her early Orthodoxy. In 1402, he took up the post of preacher in a Bethlehem chapel (private church). In his sermons in Slavonic language, he taught the people faith and life according to the Gospel, which in turn forced him to make sharp criticisms of the Catholic priests and monks. Familiarizing himself with Wycliffe’s writings, he sympathized with them, but did not share their extreme views. The upholders of Latinism began to accuse Huss of Wycliffe’s heresy. Shortly after, there was a confrontation. Two theologians — followers of Wycliffe — arrived in Prague and presented to paintings. One depicted Christ, wearing a thorny crown and walking with His disciples toward Jerusalem — the other, the Pope wearing a three-sided golden crown and walking toward Rome, accompanied by his cardinals. Discussions commenced with the Bohemians having one voice, while the Germans and Poles, three. Not sanctioning the Anglican split from the church, Huss expressed his opposition to papacy in a spirit maintained by Wycliffe. Impelled by their nationalism, the foreign professors were against Huss. In 1408, they compiled some conclusions, in which they condemned 44 of Wycliffe’s opinions. However, in 1409, Huss received a decree from king Wenceslas, which presented the Bohemian university members with the majority of voices. Soon after, the Bohemians with Huss as their head, commenced to decisively speak out against the Roman church. The archbishop of Prague then came out against Huss. He sent a report to Rome, which in 1410, replied with a bull, directing that all of Wycliffe’s works be burned and his followers be brought to trial. It was also forbidden for them to preach in private churches. Huss appealed to the Pope, pointing out the many truths in Wycliffe’s teachings; he continued to preach in the Bethlehem chapel. The Pope demanded his presence in Rome. Owing to the intercession of the king and the university, the Huss affair ended peacefully in Prague. Soon after, in organizing a crusade against his enemies, Pope John XXIII sent a bull to Bohemia in which he granted a full indulgence to all crusaders. Huss rose against it in sermons and articles, while Jerome of Prague burnt the Papal bull. They people were on their side: unrest began. In 1413, a new bull followed, which excommunicated Huss from the Church and carried an interdictum against Prague. Huss wrote an appeal to the Lord Jesus Christ Himself, hoping to find justice on earth. At the same time, he published an article titled “About the Church,” where he argued that a true church must consist of believers. As the Pope had digressed from the Faith, he was no longer a member of the Church and his excommunication is of no importance. However, the archbishop of Prague was successful in forcing Huss out of Prague. In 1414 the Council of Constance convened. As a result of his former appeals to the Ecumenical Council, Huss’s presence was demanded in Constance. Emperor Sigismund even issued him a protective edict. Having arrived in Constance, Huss had to wait a long time to be interrogated, after which he was immediately arrested. The Emperor didn’t wish to insist on his release. The Council was annoyed over Huss’s demand that they prove him wrong in his thinking, based on the Gospel. This was regarded as heresy. The Council only sought to curb the Pope’s arbitrary powers while viewing all other matters with a narrow point of view. The future of Huss was not determined immediately, because the Council was dealing with the matter regarding John XXIII. Interrogation of Huss took place in prison. After 7 months, he was summoned to the solemn sitting of Council so that his matter can be concluded. He continued to insist on being shown his errors, based on the Gospel. The Council recognized him as a heretic and condemned him to be burned at the stake. On the 6th July, 1415, Huss died at the stake. Jerome of Prague, who arrived with Huss, was also burned at the stake in 1416 after a lengthy incarceration. However, the reformist movement in Bohemia didn’t end. After Huss’s death, the Bohemians, who had supported Huss before and after the Council sitting, revolted en masse against the Roman Church. Huss’s followers (Husseites) — with his permission — introduced a dual Holy Communion. While the Constance Council rejected this as heresy, the Bohemians decided to defend this with force of arms. Many citizens and nobility joined the Husseites. John Zizka became their leader. He and 40,000 of his adherents fortified themselves on a mountain, which he named Tabor. In the Czech language, a fortified camp is called Tabor, hence they began to call themselves Taborites. They were the left-wing part of the Husseite movement. Their religious element was evident in divine services, where the clergy took confessions, preached and gave Holy Communion in two forms. They practiced brotherly, communal dining and strived to maintain moral purity. At the same time, nationalistic and social questions had immense significance within the movement. The Taborites aimed at eliminating German rule and establishing a self-sufficient and independent Czech nation. The lower classes were imbued with hatred toward the Catholic clergy, who lived in luxury while burdening them with tithes and taxes. As an example, the archbishop of Prague owned 900 villages and many towns, which equaled possessions those of a king. The Taborites, living in their mountain and harboring hatred toward the clergy and the affluent classes, destroyed many churches, and carried out many discreditable acts. Their ideal was a democratic republic, rejecting secular and spiritual hierarchy. When Wenceslas — king of Bohemia — died in 1419, the Bohemians refused to swear allegiance to the new emperor Sigismund, because he betrayed Huss. All of Bohemia upraise against him. Pope Martin V, sent a number of armed crusades against them, which achieved nothing. The Bohemians were successful in repelling these attacks. Victories of Procopius the Great -their second leader — created great fear among the bordering nations. This situation continued until the convening of the Basle Council in 1431, where it was decided to attempt a reconciliation between the Husseites and Rome. By this time the Husseites had divided into two parties. The more moderate party, which was against extreme views, agreed to the reconciliation under certain conditions — the retention of dual Holy Communion, sermons to be in their native tongue, the clergy denied of church possessions and that they be subjected to a stern church court. These Husseites were also called the “followers of the chalice” and Utraquists. The other Husseites — Taborites — having reached a stage of fanatic hatred, made additional demands of iconoclasm, abolition of Confession etc.. In response to an invitation from the Basle Council in 1433, the Husseites sent a delegation of 300 men. Prolonged meetings didn’t produce any results, so the Husseites departed for home. The Council sent a deputation after them with a compromise offer. The Council was prepared to the 4 demands of the Chaliceites, who in turn joined the Church. However, in 1462, Pope Pius II declared all these concessions as null and void. Following this, the Chaliceites performed the dual Holy Communion clandestinely. Even after Basle Council’s concessions, the Taborites remained irreconcilable enemies of the Roman Church. Having suffered a savage defeat in 1434 — from the Catholic forces — they were forced to calm down. Around 1450, the remaining Taborites formed a small order under the heading of b ohemian or moravian brothers, which renounced arms and strove to lead their lives according to the strict teachings of the Gospel. In the 16th century, it began to spread and achieved the same level of importance as other religious orders, which appeared after reformation.

Savonarola Attempts to bring about Church reform appeared even in Italy, close to the Papal throne. In Florence, a Dominican monk — Girolamo Savonarola — emerged as a Church reformer. He led a disciplined life but was a zealous and captivating individual. During his time, the so-called renaissance of the sciences and the epoch of humanism in Italy, began an intense study of ancient pagan classics among the Italians, which reflected destructively on their spiritual outlook. The mixture of pagan and Christian outlooks, brought society to a new classical paganism. Religious understanding was so entangled in Rome that Christ was often confused with Mercury and the Madonna with Venus. Religious ceremonies were performed in honor of Virgil, Plato and Aristotle. Even the cardinals and bishops viewed the Gospel as some sort of Greek mythology. The spread of unbelief, associated with the lowering of morals among the Popes, clergy and society in general, prompted Savonarola to take the path of reform activity. Jerome (Girolamo) Savonarola was born in 1425, in a town named Ferrara. He was a descendant of an ancient family of Padua. His grandfather was a renowned physician. His father was preparing Jerome for a medical career and tried to give him a comprehensive upbringing. Early in his life, the quiet and pensive youth displayed an ascetic beginning, a love for contemplation and a deep religious feeling. The then prevailing situation in Italy deeply distressed Savonarola. A combination of an unsuccessful romance and an attraction toward theological works, especially Thomas Aquinas, brought him to a decision to enter a monastery. In 1475, he fled secretly from the family home to a Dominican monastery in Bologna. There, he led a austere life, gave away his money, donated his books (leaving the Bible for himself) to the monastery, fortified himself against the excesses of the monastery and devoted his spare time to studying patristic heritage. It was here that he wrote his poetical work “About the fall of a church,” where he pointed out that people didn’t have their prior purity, scholarship or Christian love, and the main reason for that was the decadence of the Popes. The father superior entrusted him with teaching novices and to preach. He was sent to preach in Ferrara, then in Florence where he became celebrated as an erudite at the monastery of San Marco. Because his sermons were less successful, he left for a small township to improve this deficiency. He later captivated his parishioners with his sermons. In 1490, he was summoned to Florence by its governor, the renowned Lorenzo Medici. Once again Savonarola took up teaching in the monastery of San Marco. His fame as a preacher grew. The monastery used to swell with laymen that came to listen. In 1490, he delivered his famous sermon in which he expressed his firm opinion that it was imperative to renovate the Church immediately, otherwise Italy will be struck down with God’s wrath. He asserted that like the ancient prophets, he is just relaying God’s commands, at the same time he censured the corrupt morals of the Florentines, not being coy with his choice of words. Because some of his prophecies came true — death of Pope Innocent, invasion by the French king etc — his influence increased. His kind and sincere treatment of the brothers made him the monastery favorite, and in 1491, he was elected as father superior of San Marco. He immediately placed himself in an independent position with Lorenzo Medici, who was forced to take it into account. After his renowned sermon against the extravagance of women’s ornaments, they ceased to wear them to church. Often, under the influence of his sermon, merchants returned profits that they acquired unfairly. He declared: “The power of Italy’s sins are making me a prophet.” Through his writings, it can be seen that he was convinced in his “divine calling,” and the people believed in his prophecies. When Peter Medici became governor of Florence and the infamously immoral Alexander VI Borgia — Pope, Savonarola’s warnings became sharper. At one time — as a consequence of being banned to preach by the governor — he quit Florence. Upon returning, he undertook monastery reform. He sold monastery possessions, banned extravagance, and forced all the monks to work. In order to achieve preaching success among the heathens, Savonarola founded teaching chairs in Greek, Jewish, Turkish and Arab languages. Pope Alexander attempted to attract Savonarola to his side, at first offering him the archbishop’s seat of Florence, then a cardinal’s cap. However, rejecting these offerings from the pulpit, Savonarola started to fulminate against the papal dissoluteness. During France’s king Charles VIII entry into Italy and the expulsion of Peter Medici from Florence, Savonarola became its true overlord. He restored republican establishments and carried out a variety of political and social reforms. Through his proposal, the Great Council — reinstated anew — replaced the land tax with an income tax, and freed borrowers from their debts. Decisive measures were undertaken against usurers and money-changers. Savonarola proclaimed Jesus Christ to the Senior and to the King of Florence, while remaining in the eyes of the people as Christ’s chosen one. He also attempted to transform Florence morally. In 1494, a strong transformation was already noticeable: the Florentines began to fast, attend church, and the women stopped wearing expensive adornments. The streets resounded to the singing of Psalms instead of songs and only the Bible was read. Many eminent people isolated themselves in the monastery of San Marco. He nominated sermons during the hours of ballet and masquerades; the people flocked to him. Savonarola decreed that sacrilegists have their tongues torn out and the debauchers — burned alive. Inveterate gamblers were punished with huge fines. He had his own spies. The people on Savonarola’s side were common people, a party of “whites” that were called "weepers." The ones opposing him were called “the possessed” — followers of the aristocratic republican rule, and the “gray,” who supported Medici. In his sermons, Savonarola didn’t spare anyone and as a consequence had many enemies among the lay, as well as the clergy. On a number of occasions, preachers emerged opposing him; the Pope banned him from preaching. However, his fame spread beyond the boundaries of Italy. His sermons were translated into foreign languages, even in Turkish for the sultan. Strong intrigues were maintained by Peter Medici. Savonarola’s enemies turned the Pope against him, who invited him to Rome; but he refused to come due to illness, and continued his sermons of censure. The Dominicans, appointed by the Pope to examine the substance of his sermons, found no grounds to accuse Savonarola of heresy. The Pope, once again, tried unsuccessfully to offer him the purple robes of a cardinal. Enjoying a popularity, strengthened through the saving of Livorno that was besieged by the emperor — which was predicted by him and defended by his faithful “VALORI” — Savonarola decided to strike a decisive blow against “the possessed.” He organized a squad of boys who, barged into eminent homes to see if the 10 commandments were being fulfilled, ran around the city confiscating playing cards, dice, secular books, flutes, perfumes etc. after which there was a ceremonial burning of these items in the city square. Secular books on humanism and classical antiquities were irreconcilable enemies to Savonarola. He even argued about the evil of the sciences in general. A society of degenerate youths was formed, who tried to kill him. On the 12th May, 1497, having labeled the teachings of Savonarola as “suspicious,” Pope Alexander VI excommunicated him from the Church. However, Savonarola refused to submit to this command and issued “an epistle against the falsely obtained bull of excommunication.” At the same, he issued his work “ Triumph of the Cross,” where he defends the true Catholic faith and explains the dogmas and mysteries of the Catholic Church. On the last day of the carnival in 1498, Savonarola performed a triumphant liturgy and “the burning of the anathema.” The Pope demanded he stand trial in Rome so that he may be imprisoned; threatened the whole of Florence with an interdict and excommunication of everyone who listens to Savonarola. However, the latter continued to preach, arguing the essentiality of convening an ecumenical Council as the Pope may be in error. After the Pope’s second decree — "breve" — the Florence authorities, signoria banned Savonarola from preaching. On 18th of march 149, Savonarola bid farewell to the people. He wrote “A letter to the emperors,” in which he urged them to convene an ecumenical council so as to dismiss the Pope. The letter to the French king Charles was intercepted and ended up in the Pope’s hands. The Florentines were worried. In order to test the righteousness of Savonarola’s teachings, a “God’s trial” was appointed — trial by fire. This was a trap organized by Savonarola’s enemies — “the possessed” and Franciscans. On the 7th of April. Savonarola and a Franciscan monk had to walk through fires. However, this never occurred. Disillusioned in their prophet, the people started to accuse him of cowardice. The following day, the monastery of San Marco was besieged by an irate mob. Savonarola and his friends were imprisoned. The Pope appointed an investigative committee of 17 individuals, selected from the party of “the possessed.” Savonarola’s interrogation and abuse was conducted in the most barbarous manner. They abused him 14 times a day, forcing him to contradict himself; through interrogation and threats compelled him to acknowledge that everything he preached were lies and deception. Savonarola was still able to write a final work. At the request of his jailer, his last work “Guidance in a Christian life,” was written a few hours before his death on a cover of a book. On the 23rd of May 1498, in the presence of a large crowd, Savonarola was hanged and his body burned. Savonarola’s teachings were vindicated by Pope Paul IV (1555-59), while in the 17th century, a church service was created in his honor. However, his activities evoke divided opinions. Some idealize his honesty, candor and broad plans, and see him as a reformer that exposed the corruptness of the Church. Others argue that he lived with ideas of the middle-ages; that he didn’t create a new church, but retained a strong Catholic essence; that in emerging initially as a reformer, he intermingled politics into his work and appeared as a demagogue, which is what brought about his downfall.

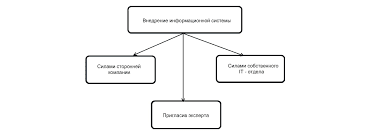

Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ, КОГДА МЫ ССОРИМСЯ Не понимая различий, существующих между мужчинами и женщинами, очень легко довести дело до ссоры... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|