|

|

Arts graduate—graduate of the arts facultyarts people—those who are studying, or have studied arts subjects. In the latter sense it means the same as arts graduates but is more colloquial and puts less emphasis on the qualification. Arts and arts subject can also be used with reference to schools. With the development of the natural sciences, arts came to be widely used in contrast to science, the sciences.

e.g. a. Girls still tend to specialise in and boys in b. In his famous lecture "The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution" (1959) C. Р. Snow stressed the need to bridge the gap between the arts and the sciences. All those expressions with arts given above can be contrasted with corresponding ones using science. e.g. science subject/faculty/student/courseldegree/graduate Science people is sometimes used, but scientists is more common (see unit 415). The arts and the sciences in this sense are two distinct categories. Thus a subject belongs either to the arts or the sciences, but not to both, although there are a few borderline cases, such as geography and psychology, which are mentioned under faculty of arts (see unit 81). Apart from these categories, however, the words art and science are used more loosely, and the meanings sometimes overlap. Thus science can be used of any subject which demands a systematic approach based on facts; art can be used of anything which needs skill, judgement and experience. For example, one may speak of the science of linguistics, even though linguistics is taught in the arts faculty, and the art of the surgeon, even though medicine is based on the sciences. The distinction between an art and a science in this wider sense is very subtle, and anyone wanting a fuller treatment of the question should consult Fowler's MODERN ENGLISH USAGE, under the heading "Science and art". The liberal arts is used in the sense of arts given at the beginning of this unit, mainly in the USA. Webster defines it as "the studies (as language, philosophy, history, abstract science) in a college or university intended to provide chiefly general knowledge and to develop the general intellectual capacities". There are many liberal arts colleges in the USA. 393. career This word is widely used with reference to education, which is often regarded, at least partly, as a preparation for a career. Most schools provide careers advice/guidance/counselling for senior pupils and some have a special careers master/mistress in charge of this. All local education authorities have a careers service, which gives vocational guidance to schoolchildren, especially school-leavers. Universities and colleges generally provide information, and sometimes also advice, about careers open to graduates. Career(s) in such cases is to be translated as профессия, профессиональный. Other examples of this use are: a. Choosing a career is sometimes very difficult. b. Teaching is a demanding career. е. Should all careers be open to women? d. It is often difficult for women to combine a career and a family. Career differs from profession, occupation and job (see unit 410) in that it often means more than simply a sphere of activity or a way of earning one's living. It implies advancement, gradual promotion to more difficult and/or responsible work, and is therefore used only of those occupations where this is possible. Note that it does not generally have the derogatory connotation sometimes present in the Russian word карьера. Career is also used in the sense of professional/creative activity or life. e.g. е. Graham Greene began his (literary) career as a journalist. f. Conan Doyle practised as a doctor for a few years but finally gave up his medical career to become a full-time writer. 394. college This word has various meanings, as follows: (1) The main meaning is an educational establishment other than a university for people who have left school (see units 37-44). The use of college in sixth-form/tertiary college (denoting a school) can be explained by the fact that this is a separate institution for pupils of 16-18, that is, for those above the minimum school-leaving age (see unit 17). (2) In American English college is widely used to denote any e.g. At the end of the last year of high school the student has to decide whether or not to go to college. (3) College may also denote an establishment which forms

Oxford Cambridge Durham London —see unit 31

Wales — see unit 32 The structure varies from one university to another, and some people would say that only Oxford and Cambridge are truly collegiate, describing the others as, for example, federal. However, they all consist of partially independent units called colleges and have certain common characteristics. Each college has its own building, staff and students, but prepares these students for common final examinations, and degrees are awarded by the university, not the college. Most of the teaching is done on a college basis, but there is also some inter-collegiate teaching, especially lectures. Unlike schools within a university (see unit 414, meaning 3), all or most subjects are studied in each college. College in this sense is used as follows: a. Andrew is at Balliol College, Oxford. b. King's College, Cambridge, is famous for its choir. (4) American universities are divided into colleges (or schools) (5) A university college is an institution between an ordinary the work was of university standard, but that the college did not have the right to award its own degrees. It prepared students for external degrees of London University. There are no university colleges in this sense in Britain now, although they still exist in some English-speaking countries abroad. Note, however, that University College is the name of two colleges in sense (3) above: University College, Oxford, and University College, London (see unit 31). (6) College may also denote a professional association, as in: The Royal College of Surgeons or The Royal College of Physicians. This is an archaic sense of the word college, given in the SOED as: "an organised society of persons performing certain common functions and possessing special rights and privileges." It has survived only in a few cases like the ones quoted above. They are not educational establishments, although they conduct examinations and award a fellowship of the college to successful candidates. This is a high professional qualification. 395. compulsory The word is more often used than obligatory in the context of education. e.g. a. Attendance is compulsory. b. The wearing of school uniform is compulsory. е. Physical education is compulsory in most English schools. We speak of compulsory subjects/courses. The opposite of compulsory is optional (see unit 412). 396. course In an educational context course means a complete period of study, irrespective of its length. A course may last only a few days, or several years. Here are some examples of usage. a. First degree courses at English universities usually b. In the second year of their course students attend е. Polytechnics offer a wide range of advanced courses in many subjects. A. Dr. Gowan is giving a course of lectures on modern American poetry. There are many types of course, for example: Introductory course Basic course Beginners' course elementary/intermediate/advanced course— often used as categories when defining the level of a course. refresher course —strictly speaking, a course aimed at bringing back forgotten or half-forgotten knowledge or skill. In practice, however, there is a tendency to use it in a wider sense, corresponding to курс усовершенствования. in-service training course —course for those already exercising a profession (see unit 168) vacation course — course held during the university vacation. However, a course held during the summer vacation is often called a summer school. intensive course — course in which a lot of material is covered in a short time, often by means of very frequent lessons crash course (colloquial)—the same as an intensive course, although sometimes it means particularly intensive sandwich course —course consisting of periods of study alternating with (or sandwiched between) periods of work, usually in industry. Such courses are very wide-spread in technical institutions. A student attending such a course is called a sandwich student. correspondence course —course in which tuition is given by post. In England such courses are mainly organised by separate establishments, usually private, and known as correspondence colleges. These colleges prepare their students for a wide range of examinations, from the General Certificate of Education (see unit 340) to external degrees of London University (see unit 96). The subject of the course may be specified, as in language/ phonetics course, English (language) course, etc. The preposition in may be used with the subject of the course, especially when it consists of more than one word. e.g. a course in the history of art When both forms are possible, as in, for example, an English (language/literature) course or a course in English (language/literature) the second form is restricted to formal style. With a more specific subject the preposition on is preferred. e.g. a course on, audio-visual methods of teaching The distinction between in and on with course is the same as with lecture (see unit 273). The expressions to go/be on a course and to do/take a course are widely used in everyday speech with reference to short courses, for example, in-service training courses. e.g. а. Гт going on a course next month. b. — Where's John? I haven't seen him lately. — He's on a course in London. е. She did/took a course on audio-visual methods of teaching last year. Note the use of the singular form course in such sentences. Note also that do/take (a course) often correspond to (о)кон-чить (курсы). Finish a course is used only in the sense of "attend to the end". Graduate is not used with course. Course work means all the work done by a student during a course, usually written work. It is used in such sentences as: There is a final examination, and the students' course work is also taken into account. 397. curriculum (pl. -a), extra-curricular This means what is taught in an educational institution, usually the subjects taught. e.g. a. The secondary school curriculum includes mathematics, science, English, foreign languages, history and geography. b. A second foreign language has been introduced into the curriculum. е. Greek has been taken off the curriculum. d. Latin is still on the curriculum of many schools. e. The university curriculum is more academic than that f. Curricula in the Soviet Union are uniform throughout Sometimes curriculum is used with reference to the material taught, in practically the same sense of syllabus (see unit 416), although mainly in a wider, more general context than that of the individual school. e.g. g. Several years of research culminated in basic changes in the science curriculum. Extra-curricular activities is used to denote activities such as clubs, choirs, dramatic productions, educational visits, trips, etc. which are not part of the curriculum. This is the official term, which is used in formal situations. e.g. h. Extra-curricular activities play an important part in the life of a school. In everyday situations the expression out-of-school activities is often used, because such activities are held out of school time. After-school activities is also sometimes used, since most of them take place after school (meaning after school hours), although some are held in the dinner hour. e.g. i. This school organises a wide range of out-of-school activities. j. We need an enthusiastic teacher who is willing to help with after-school activities. Extra-curricular activities is used only with reference to schools. Students have societies and clubs (see unit 144), but these are not called by any collective name. 398. to educate, education, education(al)ist, educator To educate is used mainly in the passive, meaning "to receive one's education", and is formal style. e.g. Mr. Borman was educated at Colchester Grammar School and London University. It may also be used in the sense of "to train". e.g. People must be educated to make the best use of their leisure time. Although it is more often used in the passive, as in the above sentences, examples of active use also occur. e.g. At one time it was widely believed that there was no need to educate girls. Word combinations using the past participle, such as an educated/'well-educated/'uneducated person are common, and not restricted to formal style. Education is used not only in the sense of "образование" but also in the sense of "педагогика". (Pedagogy and pedagogics are rare words.) e.g. college of education (see unit 38) faculty/department of education (see unit 87) institute of education (see unit 165) education lecture/lecturer or lecture on/in education, lecturer on/in education The use of the last-mentioned expressions can be illustrated by the following sentences: a. Mr. Morris is a lecturer in education at London University.

b. Students attend lectures on Educational has two uses: (1) connected with education in its main sense; e.g. an education institution/establishment an educational programme (e.g. on radio or television) educational theory/philosophy/history/progress/reform! policy (2) promoting smb.'s education, instructive; e.g. a. The school organises regular educational visits. b. This toy/game is not only amusing but also educational. An education(al)ist is a specialist in educational theory and/or practice, often a writer on the subject. The form without -al- is more common nowadays. A specialist in methods of teaching is not an educationist, but a methodologist—Russ. методист (see unit 167). Educator has come into use recently in England from America, apparently as a more dignified and formal synonym of teacher. This use is illustrated by the following quotations from a report on a visit to the USSR organised by the London University Institute of Education (see unit 165). a. We were forty-two academics and educators from twelve b.... on the side wall were two superb marquetry This use seems to correspond to that of педагог. It is restricted to professional language. 399. establishment This word is used interchangeably with institution in 208 the expressions educational establishment/institution, further/ higher educational establishment/institution, where it corresponds to заведение. 400. grant A grant is something granted, meaning given formally, especially a sum of money given by the government for a certain purpose. For example, the government makes grants to the universities (see University Grants Committee, unit 28) and to students, to support them while they are studying. The latter type of grant is called in full a maintenance grant (from the verb to maintain, meaning "support"), and is intended to be spent on food, clothes, books, fares, etc. The full form is used only in formal situations, or to distinguish this type of grant from grants for other purposes (e.g. book grant, building grant). In everyday speech the form (student) grant is used. e.g. a. (Student) grants are paid three times a year in England, at the beginning of each term. b. The amount of the grant depends on the parents' income. е. (One student to another)— Where are you going? — To get my grant. Grant here corresponds to стипендия. Stipend is not used in such cases. This word is defined by the COD as: "fixed periodical money allowance for work done, salary, esp. clergyman's fixed income". Even in this sense it is rarely used. Salary is used instead. It is true that stipend is occasionally used in official language as a translation of стипендия but this is not to be recommended on the whole. 401. humanities The humanities is defined in the SOED as: "learning or literature concerned with human culture, as grammar, rhetoric/ poetry, and esp. the Latin and Greek classics". Thus its original meaning was more restricted than arts (see unit 392). In modern English, however, it has come to be used in a wider sense, sometimes as a synonym for arts, sometimes in a still wider sense, to include such subjects as the social sciences. Here are some examples of usage. e.g. a. This college offers a wide range of courses, mainly in the humanities. b. Students of the humanitis are unfortunately often ignorant of modern scientific developments. Institute, institution The word institute has a very general meaning, and by itself does not denote a particular type of establishment. The SOED defines it as: "a society or organisation instituted to promote literature, science, art, education, or the like; also the building in which such work is carried out". Institute may denote a wide variety of things, depending on the words which modify it, and sometimes also on the context. (1) One of the most wide-spread types of institute is the re (2) There are also institutes attached to some universities, A university institute of education, however, is slightly different. This is an organisation within a university (collegiate or non-collegiate) which supervises and coordinates the training of teachers in its area, conducts educational research, etc. (see unit 165). (3) Evening institutes are establishments organised by the

twice a week. evening/night school, evening classes. (4) The British/French/Italian Institute, etc. are centres (5) The Women's Institute is a nation-wide society for women (6) Many professional associations are called institutes. One such institute is the Institute of Linguists, which Barnard and Lauwerys (in A HANDBOOK OF BRITISH EDUCATIONAL TERMS) describe as follows: "A professional association for practising linguists, the Institute conducts qualifying examinations for entry to the profession. Its members follow a code of ethics. The Institute is concerned with the rates of payment to members, whether as salaried members of organisations, or as free-lance interpreters, translators, teachers and so forth. It is also concerned with the standards of language teaching and professional training in the UK." Other institutes of this type are: the Institute of Journalists, tht Royal Institute of British Architects, the Royal Institute of Chemistry. They should not be confused with colleges or research institutes. They sometimes undertake a certain amount of research (into problems concerning the profession) but they do not provide tuition. (7) Some charitable organisations are called institutes. e.g. the Royal National Institute for the Blind More often, however, such organisations are called societies. There are many other kinds of organisations called institutes, which cannot be given here. However, the uses listed above show clearly that the word institute has a wide variety of meanings, some of them quite unconnected with teaching. Thus to speak of an institute or institutes is to give a very vague impression indeed, and provokes the question "What sort of institute?" institution—see establishment (unit 399). 403. to instruct, instruction, instructor Instruct is not much used in schools, colleges and universities. It often refers to practical skills. One may, say, for example:

He instructed them However, it is more usual, and less formal, to say: He taught them how to use the film projector. Instruction is sometimes used in education in the sense of teaching, mainly in formal style. Unlike the verb, it does not refer especially to practical skills. e.g. a. It was decided that the language of instruction should be Welsh, not English. b. The school librarian's course at Sheffield consists of three periods of instruction given during school holidays. е. In the more advanced type of laboratory, instruction is given to the pupils by speech pre-recorded on the tape. d. Although they (=nursery schools) are called Instructor is not used in England of a teacher in a school, college or university. An instructor is someone who teaches a particular skill, often connected with sport, and usually in some special establishment. e.g. a swimming/skiing/driving instructor In the USA, however, instructor also denotes the lowest grade of university or college teacher (see unit 163). 404. to learn, to study and alternatives To learn means "to get knowledge of (some subject) or skill in (some activity), either by reading, having lessons, or by experience". e.g. a. / learn French/biology/typing at school. b. She's learning to play the piano. e. Some children learn to read before they start school. d. He learnt to swim in the summer holidays. e. You are to learn the new vocabulary for homework. Learn may have either an imperfective meaning (as in examples a, b) or a perfective meaning (examples с—е). It may mean "to learn by heart", as in example (е) above, and in f. / want you to learn the poem (by heart) for next To study means "to give time and attention to gaining knowledge, especially from books, to pursue some branch of knowledge". Unlike to learn, it applies only to knowledge, not skill, or ability to do something. Thus one can learn to read, to type, to cook, to play the piano, etc. but not study. (Study is used with to only in the sense of "in order to", as in He's studying to be a doctor/lawyer.) With the names of subjects, for example, history/English/ physics, etc. either learn or study are possible. e.g. g. In the second form many pupils study two fofeign languages. h. He studied history at Oxford. In practice, however, the two verbs are not interchangeable. Study is restricted mainly to formal style. In non-formal style learn is preferred, at least with reference to elementary or practical knowledge, such as one acquires at school or at evening classes, for example. For instance we say: i. He learns/is learning English/history I physics at school. or use do or take instead (see below). If we meet a foreign visitor who speaks Russian we ask: j. — Where did you learn Russian? Study in such cases, besides being too formal for the situation, would imply an advanced, theoretical course, for example, a degree course at university. Study (English/history/physics, etc.) is more widely used with reference to advanced, theoretical knowledge, such as one acquires at university or college. e.g. k. He's studying English at university. Even here, however, study sounds rather formal, and tends to be replaced in conversation and informal writing by the more colloquial do (see unit 406). Learn here would imply a more practical, elementary course. With the names of authors and their works, periods 'of history, subjects of investigation, etc. study, but never learn is used. e.g. 1. This term we're going to study Chaucerf'The Canterbury Tales"/the Renaissance. m. Dr. Groves has studied the effect of chemical fertilisers on crops. In sentences like 1 do is often used instead of study in colloquial style (see below). When there is no object, learn refers to the process of acquiring knowledge. e.g. п. Some children learn more quickly than others. o. He doesn't want to learn. Study with no object generally means "to be a student". e.g. р. He's studying at London University. q. He published several stories while he was still studying. Note that we do not say * He studies at school/in the first form. but: r. He's at school or He goes to school. He's in the first form (see below). Neither learn nor study is appropriate here, nor in the translation of such Russian sentences as Как он учится? Он хорошо/плохо учится. Here we say, for example: s. — How's he getting on at school/college/university?

(very) well at school/college/university. — He's not doing very 'well at school/college/university. 405. To read is sometimes used in the se/ise of "to study" with reference to universities, mainly of the humanities. e.g. a. — She is reading English. (—She's studying English at university.) b. — He read history at Cambridge. This use of read can be explained by the fact that formerly students spent most of their time reading books recommended by their tutor (see unit 161) rather than attending lectures and classes. 406', The following ve.rbs are widely used in conversation and informal writing instead of learn or study: do e.g. a. Peter's doing English this year. b. They do two foreign languages in the- third form. е. / did. French for five.years at.school, but I can't speak a word. d. My son's doing engineering. e. We did "Hamlet"/Keats/the Civil War last term. The use of do with the names of writers and their works, periods of history, etc. is common among schoolchildren and students, but is discouraged by some teachers, who consider it to be careless. However, it is sometimes used by these teachers themselves in colloquial speech. Do with the name of a play may also mean "produce", "stage", and is not bad style. Take e.g. a. Peter's taking English this year. b. The fourth form takes two foreign languages. е. My son's taking engineering at the college of technology. have This is not quite equivalent to learn/study, but is often used instead, like the Russian у меня/у нас...

e.g. a. We have English three times a week. b. We have Mrs. Jennings for English. е. — We've got English today.

— No, we haven't. We d. We ve got Mrs. Jennings next lesson. to be at/in, to go to These simple verbs are often used in everyday speech rather than learn/study. e.g. a. Margaret's at school. This may mean that she is a schoolgirl, or that she is there at this moment.'

b. Margaret goes to school.

Cameron Road School. d. Margaret's in the third form/year. e. John's at college. This may mean that he is a college student, or that he is there at this moment. f. John's at university. This means that he is a university student. In order to imply that he is there at the moment, tke definite article is included: He's at the university.

g. John's at Redland College. Birmingham University. In examples (d), (е) and (f) goes to is possible, but unusual. 407. learned Learned is, defined in the COD as: "deeply read, erudite, showing profound knowledge (of language, profession, etc,}; pursued or studied by (of words in a language), introduced by, learned men". It occurs mainly in set expressions such as learned man/work (=book, etc.)/word/language, and seme others given below. It is used primarily with reference to the humanities, as indicated in Hornby's definition: "having or showing much knowledge, esp. of the humanities". In the expressions learned society/journal/article, however, learned has more or less the same meaning as academic (see unit 391), and applies equally to the arts and the sciences. It corresponds here to научный. e.g. a. The most famous of alt learned societies in England is the Royal Society (or, in full, the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge) for natural scientists, founded in 1662, and. election to a Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS) is an outstanding distinction, b. He has published several learned articles. Learning (п) is defined in the COD as: "knowledge got by study, esp. of language or literary or historical science". It occurs in such sentences as: a. Oxford has been a centre of learning since the Middle b. Professor Lewis is a man of great learning. In American English higher learning is used in the sense of higher education, for example in the expression institution of higher learning. Option, optional Optional means "which may be chosen or not, not compulsory" (see unit 395) and is used in such sentences as: a. Attendance is optional. b. Spanish is an optional subject.

е. There are optional Option is used in education in the sense of an optional subject or course. e.g. d. Fourth-form options include cookery, needlework, music, and a, second foreign language. 409. philology, philological, philologist Philology used to mean, according to the SOED: "love of learning and literature; the study of literature in a wide sense; literary and classical scholarship". However, the dictionary comments on this meaning "now rare", and this is borne out by observation of usage. The second, modern meaning given is: "the science of language, linguistics". In practice, philology generally denotes the study of the historical development of language, and history of language is sometimes used as a synonym. Students of languages at university often study philology as part of their degree course. For example, students of English study English philology, students of French — French philology, and so on. However, this is only one part of their course, alongside literature, translation, phonetics, etc. and it is now tending to become a smaller and smaller part. The word philology is also used of groups of languages. e.g. Romance/Germanic/Slavonic philology The study of the historical relationships between languages is called comparative philology. These terms generally refer to the work of postgraduates, university teachers and scholars, rather than to that of undergraduates (see unit 188). They are fields in which one may specialise after graduation. Undergraduates follow a more general course, which includes only a basic study of the philology of the language(s) they are studying. The only exception to this is the case of those students who choose philology as their special subject or field of study. It is clear, therefore, that the word philology is much narrower in meaning than филология and that much confusion will arise from using them as equivalents. Philological means "relating to philology" as defined above. e.g. a philological conference/seminar/article A philologist is a person specialising in philology in the sense given above. In practice, this is nearly always a postgraduate, university teacher or scholar. 410. profession, professional Profession is defined by Hornby as: "occupation, esp. one requiring advanced education and special learning, e.g. the law, architecture, medicine, the Church, sometimes called the learned professions". In traditional usage, profession is contrasted with trade, which Hornby defines as, among other things: "occupation, way of making a living, esp. a handicraft: ' He's a weaver/mason/'carpenter/'tailor by trade', lShoemak-tng is a useful trade'." Thus on forms to be filled in there were spaces for one's name, address, date of birth, and trade or profession. Nowadays the distinction between a trade and a profession is not so clear-cut, and the word profession has been extended to many occupations which formerly would not have been classed as such, for example, nursing, librarianship, journalism, management in industrial and commercial companies. But it remains associated with some form of more or less advanced study or training, and we cannot say, for example, that someone is a carpenter by profession. Nor can we ask "What is his/her profession?" if the person may be a manual worker, for example, or a shop assistant. Thus profession is not a general term corresponding to the Russian профессия. In this general sense occupation, job, career or some phrase is used. For example, on forms to be filled in, the word occupation is now generally used instead of trade or profession. In conversation we say simply, fur example, "He's a teacher/ architect/carpenter/shop assistant", without "by profession/trade", and ask "What's his/her job?" or "What does he/she do (for a living)?". For the use of career, see unit 393. Professional means "related to one or more professions" in the sense given above. For example, the professional associations mentioned under college (unit 394, meaning 6) and institute (unit 402, meaning 6) are restricted to those occupations requiring a certain level of study. Professional training is training for such an occupation. Professional, like profession, has become wider in application during recent years, but is still not a general term corresponding to the Russian профессиональный. There is no general term of this kind in English, although vocational is appropriate in some cases (see unit 420). 411. programme In traditional British English the use of programme in education is restricted to special courses and conferences, meaning the list of lectures, discussions and other events which are planned. e.g. A copy of the programme will be sent in advance to all those attending the course/conference. In American English program (Note the American spelling!) has a much wider application. It is often used in the same sense as course (see unit 396), without any apparent distinction, as illustrated by the following quotations from a conversation with American students: a. Undergraduates do a liberal arts course or a basic b. After getting his bachelor's degree he may apply In other cases, however, program has a wider meaning than course, denoting a system or complex consisting of various courses. e.g. е. Gradually the programs of junior colleges and technical institutes became more similar; junior colleges began to offer vocational courses and technical institutes introduced general courses. (from AMERICAN EDUCATION — see bibliog. No. 10) Program also occurs in the sense of curriculum (see unit 397), as illustrated by the following quotation from HIGHER EDUCATION IN AMERICA (see bibliog. No. 16). d. The programs of contemporary colleges and universities provide a startling contrast with the curriculum of a century and a half ago, These American uses of program(me) are still comparatively rare in Britain but they are gradually becoming less so. 412. project In the context of education project has recently developed a specific use which reflects a new trend in teaching methods. It denotes a task given to one pupil/student, or to a small group, usually a task requiring some sort of investigation and/or creative activity. R-. Musman writes in BRITAIN TODAY: "The project method is now a basic part of English infant and junior education and also of many secondary schools. Projects may be anything from organising an entertainment to producing a maga-zine. They are given to single pupils or to groups, and their purpose is to encourage them to work things out for themselves." Projects for older pupils may involve finding out about some'aspect of the subject being studied, by reading, visits, interviews, etc. In such cases it may result in the writing of a report, the making of a model, or the holding of an exhibition. Projects often cut across traditional subject barriers; for example, a project on a certain craft or industry in a certain town may involve geographical, historical, social and other factors. Projects are supervised by the teacher, but only in a general way; the actual work must be done by the pupils. In most schools projects are used mainly to supplement and apply classroom teaching, although in some experimental schools all teaching is done through project work. From schools project work has gradually spread to colleges and universities, especially newer institutions. Many further and higher education courses now include projects, and pne reads of project-based degrees, and research projects, mainly in the natural sciences, technology and social science. 413. scholar, scholarly, scholarship A scholar is someone who has made a profound study of a particular subject. It refers mainly, although not exclusively, to the humanities. The SOED defines a scholar as: "a learned and erudite person, esp. one who is learned in the classical languages and their literature". In practice its application is now wider than the classics, but does not usually extend to science and technology. Here are some examples of its use. a. Professor Rowe is a distinguished/eminent (classical) b. Dr. Barnett is a scholar of international repute. е. This university has produced many fine/great scholars. d. The opinion of scholars is divided on this question. e. He was neither a strong administrator nor a great f. Spelling reform will not only satisfy scholars, but Scholar may also denote the holder of a scholarship (see below, third meaning). Scholarly is close in meaning to learned, which is dis- cussed in unit 407. The distinction is that on the whole scholarly produces a more positive impression than learned. It suggests not only great knowledge, but also a systematic application of that knowledge. e.g. a. Mr Robbins is the author of a most scholarly work on the Elisabethan theatre. b. Miss Barrington shows a scholarly approach to her subject. Scholarly work (uncountable) is sometimes used in the sense of research, corresponding to научная работа. e.g. Higher educational institutions should try to relate their scholarly work more closely to future careers and to the needs of industry. Scholarship has various meanings. (1) learning, erudition, particularly in the humanities. e.g. a. Dr. Longford is a man of great scholarship. b. This work shows deep scholarship. However, it would be more usual to say: е. Dr. Longford is a great scholar. d. This is a most scholarly work. (2) the collective attainments of scholars. e.g. е. This book is an important contribution to Soviet/ world scholarship. (3) a sum of money given by an individual, a collective body, e.g. f. Michael won a scholarship to Oxford. g. The Hawkins Scholarship is awarded each year for research in music. In both these examples scholarship would be translated as стипендия. However, the word grant (in full maintenance grant) is used to denote the usual regular payment made to students by the state (see unit 400) and the expression state scholarship is no longer used. Nowadays a scholarship is a grant awarded for a special purpose, or in special circumstances. If it is'given by an individual, or in memory of him, it may be called a memorial scholarship. This corresponds to именная стипендия. e.g. the Worsley Scholarship (for physics) the William Townsend Memorial Scholarship See also example (g) above. (4) The scholarship was formerly used of the examination for free places at grammar schools, which then charged fees. e.g. He passed the scholarship. As the system changed after 1944, this use of the word has become archaic. School School has the following meanings: (1) an educational establishment for children (the most com (2) any institution giving specialised instruction, either to

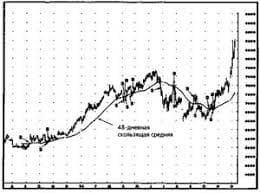

see unit 48 (3) a specialised institution which forms part of a universi the London School of Economics (LSE) the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES) the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) the School of Architecture Except in the name itself, however, these institutions are usually referred to as colleges of London University. e.g. The London School of Economics is one of the largest colleges of London University. (4) a division or unit within a (non-federal) university in (5) (At Oxford) a branch of study in which separate examina hall in which these examinations are held; (pi) these examinations. (6) (in colloquial American English) any educational insti e.g. a. What school did you go to? (meaning what college or university) b. He went to school at Harvard. (7) a course, mainly in the expression summer school (for an (8) evening/night school — colloquial alternatives to evening (9) Sunday school — classes giving religious instruction to   Конфликты в семейной жизни. Как это изменить? Редкий брак и взаимоотношения существуют без конфликтов и напряженности. Через это проходят все...  Что делает отдел по эксплуатации и сопровождению ИС? Отвечает за сохранность данных (расписания копирования, копирование и пр.)...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|