|

|

Papal Conflict With Emperors.S triving toward the realization of Pope Gregory’s theocratic plans, his successors entered into the conflict with the Emperors for ascendancy of church power over the state. Thus, Innocent II (1130-43) began to openly declare that Emperors obtained their worthiness just like a fief from a Pope. The same declaration was made by Adrian IV (1154-59) in a letter written to Emperor Frederick I Barbarossa (1152-90), from the house of Hohenstaufen. A struggle began between the Popes and Hohenstaufens on this issue, which lasted for nearly 100 years. Frederick Barbarossa came to Italy, wanting to limit Pope Adrian’s pretensions. He called an assembly, where he argued that bishops had to submit to the Emperor and that if the Popes enjoyed secular powers, it is not because of a divine right, but rather by the directive of kings that grants them this authority. Soon after the election of Adrian’s successor, opinions of the cardinals became divided. Some selected Alexander III (1159-81), opponent to the Emperor, while the others — Victor IV (1159-64), his supporter. Frederick took advantage of the situation to subordinate the Popes to his influence. He called a council and demanded that both Popes appear before it. Alexander didn’t appear at the council and committed both Victor and Frederick to excommunication. The Emperor then expelled Alexander from Rome and installed Paschal as the new Pope. Leaning on the support of the Lombard cities, Alexander was not capitulating. When matters in Italy turned unfavorable for Frederick, he made peace with Alexander in 1177, on conditions that were favorable to the Pope. Alexander’s successors were insufficiently strong to stand up to Frederick Barbarossa and his successor, Henry VI (1191). With the help of his wedding to Constance, sole heir to the Sicilian throne, Henry appended to his holdings the Norman kingdoms of both Sicilies, making him overlord of all Italy. Even in Rome, the Popes were greatly constricted under the ordinance of the Emperor’s prefect. With the death of Henry V (1197), who left a very young son Frederick, the situation changed. Constance became ruler of Sicily, while the knights in Germany decided to select a new Emperor. The papal throne was taken by Innocent III, one of the most outstanding politicians of his time. He set himself the task of realizing in all its fullness, Pope Gregory’s plan for theocracy, and was able to place papacy on such a high level, that it never experienced before nor surpassed subsequently. After ascending the papal throne, he forced the prefect of Rome to swear allegiance to him, thereby eliminating the Emperor’s authority over Rome. Replicating this in other cities within the church domain, he was able to created an independent papal kingdom. Having re-established opposition from the rest of the Italian cities to the Emperor’s authority, thereby securing their support, the Pope embarked on Sicily. He was fortunate in that Constance herself asked Innocent to confirm her son as heir, Frederick, to the dominion of Sicily, as a fief of the papal throne. Before her death, Constance (1198) in her will passed guardianship of her son to the Pope, making Innocent ruler of Sicily. Meanwhile in Germany, a fierce struggle was taking place for the country’s throne, and both pretenders turned to the Pope for help. In 1209, Innocent placed the crown on Otto of Saxon. Having received his crown in Rome, Otto violated his promise to protect all papal rights and expand them in Italy. He declared many papal lands as Emperor’s fifes and attacked Sicily. Innocent III excommunicated Otto from the church (1210) and declared that he is deprived of his worthiness to be Emperor. The Pope offered the German knights to elect his pupil Frederick II as their Emperor, which in fact they did. Innocent III also revealed his power in France, Portugal and England. With the latter, he had to endure a war with the English king John “Lakeland.” In 1207, the king refused to accept the Pope’s nominee, Stephen Langton as the Bishop of Canterbury. As a result of this battle, the Pope excommunicated John in 1209 and thereupon in 1212, deprived him of him of his throne. The people disliked the king for his cruelty and an uprising began in England. John became subdued, accepted Langton and acknowledged England to be a papal fief that was obliged to pay a tribute. It was under Innocent that a Latin empire arose, and his authority and influence spread throughout a significant part of the East. He completed his brilliant manipulation with the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), which was attended by many bishops, abbots, priors and many kings of Western Europe. After Innocents death, the Emperor’s authority became predominant over the Pope’s. Frederick II began to restore his power in Italy. He didn’t separate the Sicilian crown from the German one, as Innocent wanted. Innocent’s second successor, Pope Gregory IX (1227-42), attempted to banish Frederick from Italy and demanded the fulfillment of the promised crusade. Frederick moved on Palestine, but due to sickness among his soldiers, soon had to return. The Pope committed him to excommunication. Ignoring this and without the Pope’s permission, Frederick made a fifth crusade in 1228, temporarily seized Jerusalem from the Turks, and as a result of his marriage to Yolande — heiress to the throne of Jerusalem — and her subsequent death, crowned himself king of Jerusalem. After his return in 1229, Frederick temporarily made peace with the Pope, who was unhappy with both his successes and his actual return. Shortly after, there began a terrible hostility between them. Frederick started to appropriate papal territories. In 1239, Gregory IX again committed him to excommunication. Frederick sent an epistle to the princes and cardinals, in which he called Gregory an enemy of all governments, and promised to liberate everyone from papal tyranny. In response, the Pope sent a dispatch to them presenting Frederick as a non-believer. In 1240, the Emperor approached Rome. Counting on the French bishops as not being subordinate to Frederick, the Pope convened a council for 1241; while he in turn, seized the French bishops travelling from France. Occupying Rome, Frederick made the Pope his prisoner, who couldn’t bear the pressure and died in 1241. His successor, Celestine IV, lived just three weeks after his election. Because of dissension among the cardinals, the papal throne remained vacant for two years. In 1243, Innocent IV (1243-54) was elected and he continued his struggle with Frederick. In 1245, the Pope withdrew to Lyons, convened a council where he damned Frederick as a heretic and sacrileges, declaring his throne vacant and offering the Germans and Sicilians to choose another Emperor. Not having finished his battle with Innocent IV, Frederick II died in 1250. Having found out about this, Innocent rapturously announced Frederick’s death to the whole world as an event that was joyous to both heaven and earth. Frederick’s children, Conrad IV and Manfred, began to consolidate the Emperor’s authority, the former — in Germany, the latter — in Naples and Sicily. Conrad died shortly thereafter, leaving a son Conradin. Just as Innocent lead the battle against the Hohenstaufens, so did his successors. In order to force them out of Naples and Sicily, the Popes placed a French prince Charles of Anjou to oppose them by inviting him to Italy with a crusading army. In the ensuing battle Manfred was killed, while Conradin was taken prisoner and executed by Charles in Naples (1268), but not without the knowledge of Pope Clement IV (1265-68).

Decline of Papal Power. A fter a century of stubborn struggle against the hostile house of Hohenstaufens, the papacy gained a complete victory over them. However, this very victory was the beginning of the fall of papacy. Charles of Anjou, obligated to the Popes for his sovereignty over Naples and Sicily, and having given them a lot of promises, aspired to occupy such a position in Italy that were occupied by German Emperors. The Popes were forced to undertake measures in order to weaken his authority. Pope Nicholas III (1277-80) concluded a union with German and Byzantine Emperors, and before his death prepared an uprising in Sicily against him, known as the Sicilian supper (?). Notwithstanding this, Charles succeeded in securing such an influence in Italy that in 1281, he insisted on the election of his subordinate Pope Martin IV (1281-85). However, the more dangerous opponent for papacy was the French king Philip the Fair (1285-1315). He rejected the papal right, established by Popes, to interfere in secular matters of other states. He delivered the first savage blow against Boniface VIII (1294-1303). Philip was at war with England. The Pope offered himself as a mediator, which Philip rejected, not wanting any interference from the Pope. The Pope became indignant, having learned that in order to cover his military expenses Philip had levied taxes on the French clergy, In 1296, the Pope issued a bull (without naming Philip), in which he threatened excommunication from the church to all laymen that are applying the taxes on the clergy, and all the clergy that are paying such taxes. The Pope replied by forbidding the export from France of all precious metals. As a result, the Pope began losing his income from France, and because of this, he agreed to concessions. The clergy was not forbidden to make voluntary donations for the state’s needs. A compromise was established, and Philip even accepted the Pope’s offer of mediating in his talks with the English king. However, it was soon discovered that in the role of adjudicator between the two, the Pope was supporting the English king. Hostilities renewed and the struggle between Philip and Boniface reached extremes. In 1301, because the papal legate spoke to the king so rudely, he had him arrested, ignoring the Pope’s demands to have the matter dealt with in Rome. The Pope wrote indignantly to the king: “Fear God and preserve His commandments. We wish you to know, that in spiritual and temporal matters, you are subordinate to us… We regard those who think otherwise as heretics. “ In another letter, he offered Philip to come to Rome with the French clergy — or an authorized body — in order to explain these matters. Philip burned both letters and replied: “ Let your immense stupidity know that in temporal matters, we are subordinate to no one… We regard those who think otherwise as insane.” In 1302, Philip convened an assembly of deputies from all classes of society, who expressed the same opposition as the King’s to the Pope, and triumphantly declared that the king received his crown directly from God and not the Pope. The French clergy concurred with this. Boniface responded by calling a council in Rome and condemning the behavior of the French with a bull “unam Sanctam” (opening words), in which he developed with full determination, Gregory VII system. He declared: “Christ entrusted the church with two swords, symbols of two authorities — spiritual and secular. One and the other had been established for the benefit of the church. The spiritual authority is found in the hands of the Popes, while the secular one — in the hands of kings. The spiritual one is greater than the secular one, just as the soul is greater than the body. Consequently, just as the body is subordinate to the soul, so must the secular authority be in subordination to the spiritual one. Only under these circumstances can the secular authority serve the church beneficially. In case of abuse by the secular power, then the spiritual authority must try her. The spiritual authority cannot be tried by anyone. To separate secular authority from the spiritual one and recognize it as autonomous, means to introduce a dualistic heresy — manicheism. In contrast, to acknowledge the Pope’s total spiritual and secular authority, is to acknowledge the faith’s dogma.” Philip answered this bull by convening an assembly of government representatives, where the jurist Wilhelm Nogareaccused the Pope of many crimes, and proposed the king be authorized to arrest and try the Pope. Boniface couldn’t tolerate this; in 1303, he damned Philip, applied interdictions on France and dismissed the whole French clergy. Philip convened a third assembly. Here, his skilful jurists accused Boniface of simony and other crimes, even non-existing ones e.g. of witchcraft, and as a consequence of this, it was decided to immediately convene a council in Lyons so that the Pope could be tried and the king vindicated. Meanwhile, Wilhelm Nogare was entrusted to arrest Boniface and present him to the council. Nogare set forth to Italy; he was joined by another enemy of the Pope, a cardinal who was a descendant of Colonna and who was driven out of office when Boniface became Pope. When they arrived, they found the Pope in a small town of Anagni. In order to disarm his enemies, he met them in full papal regalia, sitting on his throne. However, ignoring his endeavors, they arrested him in his own house. They treated him so harshly that after being liberated by the townspeople 3 months later, upon his return to Rome, he went insane and died shortly thereafter (1303). Boniface’s successor, Benedict XI, realizing that his predecessor acted too brusquely, attempted to have a reconciliation with France. However, after 8 months in office, he died (1304). During the election of the new Pope, the cardinals were divided — those who had France’s interests at heart, wished to see a Frenchman occupy the papal throne, while those committed to Boniface’s interests — an Italian. Finally, the French bloc took the upper hand. The chosen Pope was an Archbishop Bertrand of Bordeaux, who took the papal name of Clement V (1305-14). Having an influence on the election, Philip the Fair secured an oath from the new Pope that he will revoke all of Boniface’s arrangements concerning him, denounce Boniface and destroy the Knights Templar. Fearing repercussions in Rome for his concessions to France, Clement decided to remain in France permanently by summoning the cardinals and confirmed his residency in Avignon. The Popes remained here up to 1377, and this nearly 70-year stay is known in history as the Avignon papal captivity. The Popes of Avignon, beginning with Clement V, became fully reliant upon the French kings and functioned under their influence. Despite this, the Avignon Popes strived to play the role of universal overlords — if not in France, then in other countries. However, they were not successful. Awareness of independence of secular powers from spiritual ones developed everywhere. Following France, the next protestations against papal pretensions emerged in Germany. The Popes sent ineffectual excommunications and interdictions — but they were ignored. In 1338, the German Emperor Ludwig of Bavaria, the dukes and electorates even decided to show that the secular power was independent of the spiritual one, by passing a triumphant act. Having declared that the papal pretensions of controlling the Emperors crown as being unlawful, they decided that future coronations will not require papal affirmation. The same thing was passed in the “golden bull” (1356) of Emperor Carl IV. During the Avignon captivity of Popes, England being totally enslaved by the Popes since the times of John Lackland, also liberated itself from their influence. During Edward III reign, feudal tributes to the Popes were terminated, as was the practice of sending appellations to Rome. Even in Italy, the power of the Popes weakened. Only in the church sphere were they formally acknowledged as overlords. Whereas in reality, neither the Pope nor his successors and legates had any influence on the running of the state.Adherents of the Pope invited them to return to Rome, fearing that if the Popes remained in Avignon, papal authority would be completely obliterated. The Popes themselves were well aware of this. Employing a mercenary force for his resettlement within the church dominion, Gregory XI (1370-78) finally moved his residence to Rome (1377), where he eventually died (1378). With his death, the Roman church experienced the beginning of the so-called Great Schism. The majority of cardinals in the papal curia were French, having come from Avignon. They insisted that the Pope be French while the Roman people demanded that he be a Roman. Eventually, an Italian was chosen as Pope — Urban (1379-89), a man of harsh and even cruel nature. The new Pope began his reign with trying to improve the morals of the clergy; this touched upon the cardinals. Insulted by this, the French cardinals seized the Pope’s valuables, left Rome declaring the election of Urban as invalid and elected their own Pope Clement VII (1379-94), who shortly thereafter settled in Avignon. Clement was recognized by France, Naples and Spain, while the other nations acknowledged Urban. Thus a dual authority appeared in the Roman church.

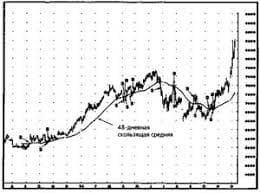

ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  Что делать, если нет взаимности? А теперь спустимся с небес на землю. Приземлились? Продолжаем разговор... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|