|

|

Papal struggles with Emperors for independence in church affairs.The papal authority that was placed on such an elevated position by Nicholas I (858-867), fell significantly in the 10th and mid 11th centuries. This came about as a result of the Italian authorities’ interference in papal affairs, and because of the moral dissipation and inactivity of the Popes and clergy. In mid 11th century, control of the papal throne was relinquished by the Italian Rulers into the hands of the German Emperor Henry III (1039-56) — from the Finnish dynasty — who restored the Emperor’s authority in Italy. As a consequence of the papal iniquities in those times (one of them sold his papacy for a large sum of money to a wealthy Roman), there arose a movement demanding the reform of the clergy. It soon found itself zealous champions and disseminators in the form of monks from the French monastery of Cluny (in Burgundy). The Clunytians preached that the clergy should reject their secular interests and worldly lifestyles. This applied especially to the Popes. Henry III was in sympathy with the Clunytians, inasmuch as it was aimed against simony and disorder in the church. Henry appointed three Popes, while the Clunytian movement aimed at freeing the church from the influence of secular authorities. A fervent champion of this concept was a monk named Hildebrand, who was made a cardinal by Pope Leo IX (1049-54) and then administered all the papal affairs for the next 20 years. At the outset, Hildebrand with the aid of some skilful politics removed the Emperor’s influence over the papacy. Son of a Tuscany peasant, Hildebrand was first the Pope’s personal chaplain, having spent some time in Cluny. Returning to Rome and supporting reforms, he occupied a prominent position, adroitly defending the independence of the papal authority. After the death of Leo IX, with changes in the papal seat of power, he acted so skillfully that the selection of the Pope, was made without any reference to the Emperor’s court — as though by chance and not by design. True, it was soon that the juvenile Henry IV (1056-1106) became Emperor. Through Hildebrand’s suggestion, he appointed Nicholas II, who decided to openly remove the Emperor’s influence in electing Popes.… In 1059, he decreed at the Lateran council that the election of Popes belongs to the College of Cardinals bishops from Roman districts, priests from major churches and several deacons attached to the Pope and his cathedral. The rest of the clergy and people had to show only their concurrence. With regards to the Emperor, he could confirm the election to the extent of the right given to him by the apostolic throne. Roman nobility was dissatisfied with being relegated to a secondary position. They asked Henry IV to take advantage of the right to appoint Popes, just as his father had done. However, Hildebrand elected his own candidate, Alexander II (1061-73). After his death, Hildebrand decided to take up the throne himself, and after being elected by the cardinals, assumed it under the name of Gregory VII (1073-85). The Emperor was simply notified of the election. Gregory ascended the papal throne, filled with those ideas on papal omnipotence, which had long ripened and developed into a whole system in his mind. Adopting the Roman church’s long-held view on the Pope as being Christ’s ruling vicar on earth, Gregory wanted to establish a universal theocratic monarchy under papal domination. According to his conception, the Pope had to rule not only over the spiritual but also secular authorities. He regarded every authority, not excluding that of the Emperor, as lower than the Pope’s. Every power receives its blessing and authority from the Pope. In cases where there is abuse from spiritual or secular powers, the Pope has the right to deprive them of their privileges that are attached to their calling, and grant those privileges to someone else, according to his discretion. According to Gregory, the Pope has the authority to grant omophorions and Emperor’s and king’s crowns. Before beginning to bring his ideas into fruition, Gregory needed to completely remove the secular influence on papal affairs. Although having rid itself of the Emperor’s pressure on the election of Popes, the investiture still remained under secular influence i.e. the right to allocate spiritual responsibilities. Consequently, Gregory immediately went about in abolishing the investiture. At a council in 1075, he passed an act banning investitures. It was decreed that those religious individuals that received their investiture from secular authorities be replaced, while those who carried out the investiture, be excommunicated from the church. The same council forbade priests to marry. In Gregory’s view, because unwedded priests were denied relatively ties with the surrounding world, this would make them more zealous workers of the church. The struggle against investiture was undermining the feudal dependence of church lands — bishop, abbot and priest must appear as church pastors and not vassals of king or prince. The clergy itself submitted unwillingly to the spiritual reforms. The decision of a celibate priesthood was received especially harshly. Some clerics rose up against the papal legates. The worst reception received for these papal decrees was in Germany. Papal legates appeared before Henry IV and presented him with the situation regarding investitures. As at that time Henry was setting out to war, he agreed to the papal demands. However, when he returned, he continued the practice of investiture. Then in 1076, the Pope summoned him to Rome to be tried. The Emperor disdainfully sent his envoys to the Pope, and assembled a council of German bishops at Worms. In fulfilling the wishes of the Emperor, the council decided that it was unnecessary to submit to Pope Gregory as he was trying to enslave the church and remove the authority of the bishops. Henry declared that the Pope is subverting social order, established on two beginnings and blessed by God’s grace — Emperor’s power and priesthood. Having mixed these two fundamentals together, the Pope should resign and give way to a worthier individual. However, Gregory was not to be frightened or driven from his path. In turn, the Pope excommunicated Henry and the bishops from the church. He declared that Henry is deprived of his regal worthiness, and that his subjects are released from their allegiance to him. He charged the German princes to select a new king. Had Henry not turned the German princes against himself by his earlier actions against them, this papal command would have had no effect. These papal allies were the same feudalists, whose influence the Pope tried to eradicate from the church. The East German dukes began a war against Henry. An uprising flared up in unruly Saxony. The spiritual hierarchy, having just expressed their opposition to the Pope, was confused by the Pope’s determination and with the common people, who due to their sympathy for church reforms, organized riots against the Pope’s enemies. The dukes, having gathered for an assembly in Tribur and decided that if Henry is not re-instated to the church by the Pope, he would be denied his throne. Henry became bewildered. In the winter of 1077, he left with a small retinue to Italy. At the time, the Pope was located at a castle in Canossa, owned by his faithful supporter countess Matilda. Having arrived there, Henry was not allowed entry into the castle. He sent an envoy to the Pope with the acknowledgment of his guilt, to express his acceptance of the Pope’s demands and to secure absolution. The Pope forced Henry to stand three days before the castle walls for his decision, dressed as a penitent in bare feet, and not eating. The Pope forgave him, but only on the condition that the matter be resolved by the German dukes at an assembly. However the humiliation, which Henry endured, proved fruitless. The German dukes not only didn’t lay down their arms, but also elected Rudolf, Duke of Swab as their king, who commenced a war against Henry. The Pope acknowledged Rudolf as king and once again, excommunicated Henry (1080). However, Henry was still able to attract a large number of supporters. Part of the spiritual hierarchy remained by his side, fearing that with the removal of their investiture they would become fully dependent on the Pope. Among those low echelon clergy were married priests. He attracted to his side, minor knights and populations of large cities, which were growing wealthy and were endeavoring to rid themselves of the oppression of seniors. In banning the Emperor, the Pope declared that the Apostles having received the authority from Christ to bind or unbind human consciences, were placed over the church and the whole world. If their successors can control spiritual responsibilities, they would more so authoritative over kingdoms and princedoms. Henry did not fall in spirit. Convening a gathering of bishops that were supporting him, he repeated Gregory’s declaration at the councils in Mölsen and Brixen (1080), and elected a new Pope Clement III. In one of the battles, Rudolf of Swab was killed and Henry consolidated his power in Germany. He then decided to end the matter with the Pope. In 1084, he stormed Rome, raised Clement to the papal throne and was crowned Emperor by him. Pope Gregory locked himself away in the castle of Sant’Angelo and firmly refused all talks with Henry. At this time, the Norman's who have conquered southern Italy came to the Pope’s aid. Their duke, Robert Guiscard, assembled a large force, which included enlisted Saracens. Henry was forced to leave Italy with the approach of Guiscard. The Norman's and Saracens savagely looted the city in front of the Pope’s eyes. Naturally, the citizens of the city were outraged at the behavior of the Pope’s allies. Realizing his grave position, Gregory VII withdrew to Salerno in the east where he shortly died in 1805, declaring to his close associates: “All my life I loved the truth and hated iniquity, for which I now die in exile.” The Roman church canonized him. Popes Victor III (1086-87), Urban II (1088-99) and Paschal II (1099-1118), that controlled the Roman church after Gregory, were all his students and tried to realize his plans. Consequently, the struggle against investiture continued. They demanded its abolition, subjected Emperors to excommunication from the church and organized political unions against them. Henry IV, his son Henry V and their troops used to come to Italy, drive out the Pope and restore the antipope Clement. Pope Urban was especially resolute in his battle against Henry IV. In 1092, he was even able to provoke Henry’s son Conrad (who eight years later ruled Lombardy and Tuscany) against him. Urban’s sermon in Piacenzaand Clermont (in France), aroused fanatical inspiration among the masses, which he was able to utilize for his own purposes. In 1096, while marching through Italy, the crusaders helped him to drive Clement out of Rome and subdue the Roman nobles that maintained the Emperor’s side. Urban then occupied the papal throne. Urban’s successor, Paschal II was able to completely dislodge antipope Clement from the domain of Rome, whereupon he died in that same year. Henry IV could do nothing with Urban II. The domain of countess Matilda barricaded Rome from the north and the support of the Norman's in the south, ensured protection for the Pope. Advanced in age, Henry IV was obliged to go to war against his son Henry. In 1106, their forces met on the banks of the river Rhine, where Henry IV died suddenly. The son was conditioned to oppose his father by the Pope, who sent him flattering letters with requests “to show some help to God’s church.” Initially, Henry V followed in his father’s footsteps. Countess Matilda died, leaving her huge estate to the Roman throne. Henry V didn’t want to allow this strengthening of the Pope’s secular possessions, and continued to insist on the Emperor’s right of investiture of hierarchy clergy in the German and Italian kingdoms. Although he occupied Rome, his precarious position in Germany once again performed a great service to the Popes. Both sides had been fatigued through battle. During Pope Callistus II (1118-24) at the assembly in Worms, the Pope concluded a very favorable treaty for himself with Emperor Henry V and the German knights. On the basis of the 1122 Worms’ concordat, the Pope, as a spiritual figure, was presented with the right to spiritual investiture i.e. the right to select and ordain bishops and abbots, in conformity with church laws, together with bestowing the ring and scepter. The Emperor, as a secular head, was accorded the secular investiture i.e. the right to grant the same bishops and abbots, princely rights, land holdings etc., while accepting from them their feudal allegiance. For a time, discords and disorders that separated the western Christian world ceased.

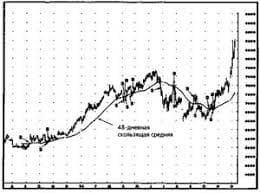

ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между...  ЧТО И КАК ПИСАЛИ О МОДЕ В ЖУРНАЛАХ НАЧАЛА XX ВЕКА Первый номер журнала «Аполлон» за 1909 г. начинался, по сути, с программного заявления редакции журнала...  Что будет с Землей, если ось ее сместится на 6666 км? Что будет с Землей? - задался я вопросом...  Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|