|

|

Beginning of the Separation.I n the middle of the 9th century, conditions became right for the commencement of the separation. The following served as the cause. Upon the death of Emperor Theophilus in 842, his six-year-old son Michael III inherited the Byzantine Empire. His guardians-rulers were: his mother Theodora, kooropalat Theoktist,patrician Bardas, the empress's brother and general Manuel. After the cessation of iconoclasm, Saint Methodius was elevated to the post of Patriarch. After his death in 846, the Patriarch’s throne passed to Abbot Ignatius, son of Emperor Michael Rangebé, well known for his pious life. Becoming of age, Michael III handed over the affairs of the state to his Uncle Bardas and surrendered himself to drunkenness and debauchery. In 854, he overthrew his mother and incarcerated her in a palace at Cariana, and contrary to the will of the Patriarch, he forcibly had his mother tonsured at a monastery in 857. Having banished his wife, Bardas began living with his daughter-in-law. After fruitless admonishments, the Patriarch refused him Holy Sacraments on the day of Theophany. Bardas came to hate the Patriarch and began to incite Michael against him, finally succeeding in having the holy father banished to the island of Terebinthus. In 857, Photius was forcibly elevated to the Patriarch’s throne. He was around 60 years old (his brother was married to Emperor Theodore’s sister), was outstanding in his love for the sciences and education, having at one time taught Emperor Michael and Constantine the Philosopher, and more recently was the government’s first secretary. In a matter of days, he passed the stages of reader, deacon, priest and finally, ordained as bishop. Upon becoming a bishop, he gave the council of bishops a written assurance that he was not guilty of dismissing Ignatius, and that he will always treat him with respect. Ignatius had decreed excommunication to all that do not recognize him as Patriarch. In 859, the local council of bishops in Constantinople met Ignatius’ conduct with disapproval and endorsed Photius as the head. Despite Photius’s intercession, Patriarch Ignatius’s supporters were subjected to persecution by those (they were called “akribeets”) who regarded it essential to conduct a merciless struggle against iconoclasts. Photius’s supporters, so-called “economy,” had a condescending attitude toward heretics, and the enmity between the two sides was becoming more aggravated. In order to end these church disorders and through Bardas’s advice, Emperor Michael decided to convene a great council and invite Pope Nicholas I to attend. The council was called in Constantinople in 861. The Pope was sent letters of invitation by the Emperor and Patriarch. Although the Emperor hid the real purpose of the council, Nicholas was well aware of the hierarchical upheaval, and as he aspired to realize Isadore’s false decretals about the Pope’s omnipotence, hastened to take advantage of the situation so as to make himself arbitrator of the Eastern Church. He sent two legates to the council with letters to the Emperor and Photius. He wrote to the Emperor in arrogant terms, that he had acted against church rules, having dethroned one Patriarch and replacing him with another without the Pope’s — his –knowledge; at the same time accusing Photius of being ambitious and illegally accepting the Patriarch’s post, because church rules forbid the instant elevation of a laymen through all church levels; moreover, he added that he will not recognize him as the Patriarch until such time as the legates had sorted out this matter. Actually, a council was convened at Constantinople in 861, with the attendance of the Pope’s legates. However, contrary to the Pope’s expectations, the Eastern fathers acted independently, outside his influence. Ignatius was regarded as dethroned, while Photius as the legal Patriarch of Constantinople. The determinations of the council were relayed to the Pope by the legates for his information. Photius also enclosed with this information, his own letter of response to the Pope’s accusations, explaining with dignity that he agreed to the Patriarch’s post not because of ambition, as he didn’t seek it, but because he was forced to accept it. Regarding the violation of rules, Photius pointed out that these regulations are decisions of local churches and are not obligatory to Constantinople, and that even the Western church permits these enactment's. Furthermore, Photius mentioned to the Pope that in being concerned for church harmony, the Pope himself had violated this as he was associating with runaway spiritual figures from the Constantinople patriarchate, who had no accreditation. Nicholas was extremely displeased with the conclusions of the council and Photius’s letter. He most probably, would have recognized Photius as Patriarch of Constantinople, if he hadn’t seen in him a firm opponent to his pretensions to being the head of the Church. He now begins the struggle with the Eastern church, figuring to vanquish Photius and then subject the eastern church to his influence — just as the western churches. With this in mind, he sent a letter to Emperor Michael. Assuming the tone of a judge, he expresses in it that with regard to Ignatius and Photius, he doesn’t recognize the council’s determinations, and that he charged his legates to sort out the matter and not decide it. Also, that he now declares Photius as having his post as Patriarch revoked, while ordering that Ignatius be elevated to this post without any scrutiny etc. In his letter to Photius, the Pope again argued the illegality of his appointment as Patriarch, and that if they don’t have any rules forbidding such appointments, then they exist in the Roman church, which is the head of all churches and because of this, everybody must abide by its decisions. Whereupon, the Pope convened a council of his bishops in Rome (862), where he damned Photius and reinstated Ignatius. Apart from this, he sent a circular epistle to all the Eastern bishops, calling on them to cease relations with Photius and deal with Ignatius. Of course, Constantinople didn’t take heed of the Pope. The Emperor sent him a sharp letter, in which he unashamedly expressed the bitter truth to him — that he as Pope, is meddling in other’s affairs and that church of Constantinople does not recognize his right to be head and judge of the Universal Church. The Pope responded with a likewise, terse letter — and the rift between the churches commenced. The question as to who controlled the Bulgarian church caused greater enmity between the two churches. As is known, the Bulgarian king Boris was christened in 864. His subjects followed suit. Just as the first Christian preachers in Bulgaria were Greek missionaries, so was the first hierarchy — bishops and priests. Boris’s fear of succumbing to Constantinople’s political and spiritual influence prompted him to seek a church union with Rome, especially as the Roman preachers had already infiltrated into Bulgaria. In 865, Boris dispatched a delegation to Nicholas I in Rome, requesting that he send some Latin priests to Bulgaria. Nicholas was overjoyed at this request and sent Latin bishops and priests. Following this, the Greek clergy were driven out of Bulgaria and replaced with the Lateens. The Pope’s clergy again began to inject their misguided teachings into the newly-created churches. Thus, the newly-christened Bulgars had to be Chrismated again on the grounds that the previous one was ineffective; changed the fast day from Wednesday to Saturday; permitted the consumption of dairy products during the first week of Great Lent; labelled the married Greek priests as being unlawful, and taught the emanation of the Holy Spirit from the Son also etc. This papal usurpation of power and the clergy’s behavior in Bulgaria, produced bad feelings in Constantinople. Photius assembled a local council, condemned all the Roman fallacies and advised all the Eastern Patriarchs of this by way of a circular, inviting them to a new council for the purpose of examining the erroneous teachings of the Roman church. This council opened in Constantinople in 867. It was attended by local representatives of the Eastern Patriarchs, many bishops and Emperor Michael himself with the new Caesar, Basil of Macedonia. Photius unveiled before the council in convincing fashion, all the fallacies of the Roman church, and proposed that Pope Nicholas be unseated. To this end, it was decided to approach the western Emperor Ludwig. The conflict between the churches took a different turn. Due to the intrigues of Basil the Macedonian, Emperor Michael III was killed and was replaced by him. His agenda didn’t include a rift with the Pope. Consequently, he decided to dethrone Photius and re-instate Ignatius. He sent a letter to the Pope in Rome, humiliating the Eastern Church. Basil subordinated the Eastern Church to the Pope by handing him Photius for his judgment, at the same time requesting his confirmation of Ignatius. However, Nicholas didn’t live long enough to savoir the moment — he died before the arrival of the messenger. The new Pope, Adrian II, hastened to take advantage of the situation that was favorable to the Roman cathedra. He convened (868) a council in Rome, pronounced an anathema on Photius and his supporters, and publicly burned the 867 Constantinople’s decrees against Nicholas, which were sent to him by Basil of Macedonia. He thereupon sent legates so as to finally resolve the matter between Photius and Ignatius, thereby confirming his authority in that country. In 869, a council was held in Constantinople, regarded by the West as the 8th Ecumenical Council. At this council, Photius was dethroned and condemned, while Ignatius was reinstated. However, worst of all was the fact that at this council, the Eastern Church agreed to all the demands of the Pope and subordinated Herself to him. The legates engaged in council matters and reasoning in the spirit of the false Isadore’s decrees about the Pope’s primacy, attempted to pass an edict forbidding even the Council to pass resolutions against the Pope. This mistake was realized by the Greek bishops only after the closure of the Council. When the legates presented the Pope with the Council’s acts, he at first confiscated them but then returned them. However, on the question of the Bulgarian Church, the Eastern bishops and even Patriarch Ignatius remained uncompromising. After the closure of the Council, notwithstanding the demands from the legates in private meetings with Ignatius and representatives of the Eastern Patriarchs, and despite their dire threats to Ignatius, the representatives found that the Bulgarian Church should be answerable to Constantinople. After the departure of the legates, Ignatius dispatched a Greek Archbishop to Bulgaria, who was accepted by Basil. At the same time, all the Latin clergy were removed. Although Pope Adrian — after learning of this — forbade Ignatius to interfere in the administration of the Bulgarian Church, this was ignored in Constantinople. Consequently, the abated disagreement between the churches flared up with new strength when Photius, once again, assumed the throne (879). After being dethroned in 869, Photius was incarcerated. Notwithstanding his confined situation, he bore this with exceptional resoluteness, continuing to oppose the subordination of the Eastern Church to Rome. He even succeeded to gain sympathy from Ignatius’s adherents and the Emperor Basil himself, who recalled him from confinement and charged him with his children’s education. Upon the death of Ignatius, the Emperor offered the Patriarch’s throne to Photius. At this time Basil didn’t value the peaceful relationship he had with the new Pope — John VIII — particularly as the Saracens had attacked Italy, and blatantly re-instated Photius. A council was held in 879 to remove the condemnation of Photius. At the request of the Emperor, Pope John sent his legates. He agreed to acknowledge Photius as Patriarch, on the conditions that Photius acknowledge that his reinstatement was due to the Pope’s mercy, as well as renounce his authority over the Bulgarian Church. At the council, the legates didn’t even raise the first condition, as they were advised that because Photius had already been recognized by the Constantinople Church, a confirmation from the Pope was unnecessary. As for the Bulgarian Church, the council explained that demarcation of dioceses rested in the Emperor’s hands. Thus the Pope’s conditions were left unfulfilled. However, the legates had to agree to the lifting of Photius’s condemnation and the re-establishment of relations with him by Rome. They didn’t even protest when the Nicene Creed was read at the council, without any additions — from the Son (filioque). It was confirmed that it was not to be changed under the threat of anathema. Having received the council acts and having learned that his conditions had not been met, Pope John VIII demanded through his legateMarinathat the Emperor rescind the council’s determinations. Because of Marina's impertinent behavior in Constantinople, he was imprisoned. Now, as it became perfectly clear to the Pope that Photius was not going to give him any concessions and he would have no influence over him, he passed a new anathema on Photius. Again, polemics and conflicts ensued between Constantinople and Rome. The ensuing Popes all subjected Photius to the same anathema, which collectively totaled 12 in all. The rift between the Churches had begun

Final Separation of the Churches in the 11th Century. A fter Photius’s second dethroning (886) by Leo the Wise and up to the middle of the 11th century, contacts between the Eastern and Western Churches were sporadic and rare. Because of their personal motives, only the Byzantine Emperors made contact with the Popes. Finally, in the middle of the 11th century, active undertakings began, culmination in a full rift between the Churches. At that time, the Pope was Leo IX, while the Constantinope Patriarch was Michael Cerularius. Leo IX tried with all his might to reassert the waning papal influence, both in the East as well as the West. His first efforts were to consolidate his influence in a number of churches in southern Italy, which belonged to the Constantinople Patriarch. Thus, the Latin outlook began to spread among these churches, and the Eucharist was performed with unleavened bread. Whereupon, Pope Leo attempted to reactivate opposition from the Patriarch of Antioch to Michael Cerularius, who in turn decided to put an end to papal intrigues. He banned Argira — commander of the Greek forces in Italy — from having Holy Communion, because he cooperated in the performance of Eucharist with unleavened bread; closed all Latin monasteries and churches so as to eliminate temptation to the Orthodox faithful, and directed (1053) the Bulgarian Archbishop Leo, to issue an epistle, condemning the new teachings of the Lateens. This epistle reached the Pope, creating a big stir in Rome. While wishing — for political considerations — to maintain peaceful relations with the East, the Pope nevertheless responded to Leo’s epistle by sending a letter to Michael Cerularius, stating that nobody has the right to judge the apostolic cathedra, and that the Patriarch of Constantinople should treat it with respect, seeing as how the Popes granted him his privileges. Because the Byzantine Emperor Constantine (1042-1054) — also for political considerations — wished for peace with the Pope, the papal letter was received favorably. Moreover, the Emperor and the Pope wanted to establish a practicable peace between the churches, and to that end the Pope sent his legates to Constantinople. Among them was a cardinal Goombert a fervent and conceited individual. Because they treated Michael Cerularius with open contempt, he refused to hold talks with them. Ignoring this and relying on the Emperor’s protection, the legates, under the guise of reconciliation between the churches, commenced to act in favor of the Roman cathedra. Thus, Goombert issued a refutal of Leo’s epistle, and the Emperor had it distributed among the people. Upon the insistence of the legates, the Emperor forced monk Nikita Steefat — author of the publication condemning the Latinos — to burn the book. Finally the legates, not hopeful of bringing the Patriarch under their influence, issued an act excommunicating him and the whole Greek Church, accusing them of all possible types of heresies. They placed it triumphantly on the altar during Mass in a church at Sophia, and left Constantinople. In the “Chronicle of Church events,” Bishop Arsenius describes the legates’ behavior thus: “And so the papal legates, weary of the opposition from the Patriarch” — as they said — “decide on a most insolent act. On the 15th of July, while the clergy was getting ready for church service at 3 o’clock on Saturday, they enter the church in Sophia and in full view of the clergy and worshippers, they place the decree on the main altar. In leaving, they shake the dust off their shoes as a testimony to what is written in the Gospel (Mat. 10:14), exclaiming: ‘Let god observe and judge.’” This is how Goombert himself saw it. Among other things, the decree spoke of: “with regard to the pillars of the empire and honored, wise citizens, then the city (Constantinople) is — utmost Christian and Orthodox. With regard to Michael, being illegally called Patriarch, and supporters of his folly, countless weeds of heresy are being scattered within him…” Further on, they are called simoniacs and compared to the worst heretics — (because they had erased from the Creed “and from the Son”; this is how little the legates knew about history!), once again, I don’t know (for permitting married clergy) etc.. Consequently “Michael, for his abuse in calling himself Patriarch, neophyte, having donned the monastic vestment through human fear, and who is now accused of grave crimes; also Leo, bishop of Akreed, a dignitary of Miguel, Constantine, who trampled the Roman sacrificial offering, and all those that share their fallacy and pride, all heretics, the devil and his demons — until such time as they come to their senses, let them be anathematized, let them be anathematized — maranatha, and let them not be regarded as Catholic Christians but heretics and prozymites). Let it be, let it be. let it be! The arrogance of the papal legates aroused the whole population of the capital against them, and it was only due to the Emperor’s respect for their status as envoys, were they allowed to leave the city. On the 20th July, at the meeting of the Patriarch’s “permanent” synod that was made up of 12 Metropolitans and 2 Archbishops, and in the presence of 7 Archbishops that were present at the time in the capital, a council epistle was drawn up. It condemned the activities of the papal legates and damned the authors of the anathema decree. This was relayed to all the other Eastern Patriarchs. In its informative pronouncements, it stated that the legates were liars that acted without the Pope’s knowledge or authority. Indeed, in September 1053 the Pope was a Norman prisoner in Beneventand after his release, died on the 19th April, 1054 i.e. 2 months before the complete rift. Consequently, it is not without foundation to conclude that the legates carried out the will of the powerful enclave of Roman cardinals, as well as those forces in Eastern Italy that were antagonistic to the Greek authorities, and in their activities, leaned on the active Latinos in the Greek empire, which are mentioned in the Patriarch’s epistle.

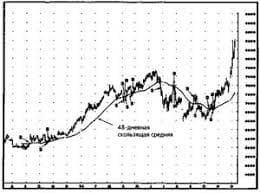

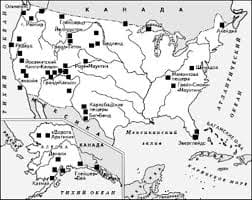

Что вызывает тренды на фондовых и товарных рынках Объяснение теории грузового поезда Первые 17 лет моих рыночных исследований сводились к попыткам вычислить, когда этот...  ЧТО ПРОИСХОДИТ ВО ВЗРОСЛОЙ ЖИЗНИ? Если вы все еще «неправильно» связаны с матерью, вы избегаете отделения и независимого взрослого существования...  Система охраняемых территорий в США Изучение особо охраняемых природных территорий(ООПТ) США представляет особый интерес по многим причинам...  ЧТО ТАКОЕ УВЕРЕННОЕ ПОВЕДЕНИЕ В МЕЖЛИЧНОСТНЫХ ОТНОШЕНИЯХ? Исторически существует три основных модели различий, существующих между... Не нашли то, что искали? Воспользуйтесь поиском гугл на сайте:

|